No Quieter Bed

Poet and professor emeritus of English Richard Eberhart ’26 leaves a legacy of lyric verse and memorable mentoring.

Sept/Oct 2005 James Zug ’91Poet and professor emeritus of English Richard Eberhart ’26 leaves a legacy of lyric verse and memorable mentoring.

Sept/Oct 2005 James Zug ’91Poet and professor emeritus of English Richard Eberhart '26 leaves a legacy of lyric verse and memorable mentoring.

ON A STORM-LASHED WEDNESDAY evening in early June at the Norwich Bookstore, across the river from Hanover, I started a talk on my new biography of John Ledyard class of 1776, by reciting, from memory, Richard Eberhart's poem on Ledyard. Two days later I did the same thing at the Dartmouth Bookstore in Hanover. Both evenings I used the poem as the framework for my presentation. I discussed how it had been the initial catalyst for my interest in Ledyard, how in "John Ledyard" Eberhart had captured Ledyard's manic, elusive personality and how the poem's reccurring line "great with desire" had been the working title of the biography. I then said that Eberhart was still living in Hanover at age 101.

I was correct on Wednesday but wrong on Friday. As I and the rest of the world learned Saturday morning, Richard Ghormley Eberhart had died that Thursdau June 9, 2005.

Fifteen years earlier, as an aspiring writer and wide-eyed junior at Dartmouth, I came into contact with Eberhart. At Sanborn House I had gotten the address in Gainesville, Florida, where he and his wife, Betty, wintered. I had written him to see if he wanted to give a reading at my fraternity, Psi Upsilon. had written back, to my surprise, and said yes.

On May 23,1990-Eberhart was a meticulous incriber his own books-Eberhart gave a reading in Psi Us living room before a standing room-only crowd of undergraduates and Upper Valley residents. I introduced him as Dartmouth's poet-in-residence—which was wrong as his term ran from 1956 to 1984-but he did not correct me. I could have added that he had won the Pulitzer, the National Book Award and the Bollingen and that he had been consultant in poetry (now poet laureate) at the Library of Congress under Eisenhower and Kennedy.

Eberhart, short, bald except for wisps of white hair around his ears and small except for his potbelly, began by saying that this was his first public reading in Hanover in 20 years. It was a strong dose of reality for a young writer—a famous poet and he had not give a reading in his hometown in 20 years?

In his high-pitched, passionate voice, Eberhart remembered his undergraduate years, drinking whiskey at Alpha Delt and the D's he got in Greek, chemistry and biology. He read "The Fury of Aerial Bombardment," his famous Second World War poem, but he passed over "The Groundhog," his most anthologized poem, saying that he felt the end was too sentimental. The poems sounded always Eberhartian, with his signature awkward syntax and obscure language ("John Ledyard" includes words such as "entablature" and "intrepidity").

Eberhart ended with the poem "Cover Me Over." He said when he was 16 and living in Minnesota, he wrote four poems one night after reading Tennyson. One was "Cover Me Over," an eight-line poem about sleep. "It was perfect, "he said without pretense, "and will long outlast me." Not a bad ratio, I thought, one immortal poem out of four.

During the next year I kept in touch with Eberhart. He invited me a number of times to his house on Webster Terrace. It was a rambling, white colonial on a deadend street behind fraternity row. We would sit at the kitchen table and he would smoke his ever-present pipe and nibble on chocolate—he was a fiend for chocolate and kept bars stashed in rooms around the house and in his car—and talk for hours on end. He spun tales from working as a deck hand on tramp freighters in the Pacific or his stint as a private tutor for the king of Siam's son—in typical Eberhart fashion he had leapt up and shaken the king's hand when he was introduced, incurring a severe scolding from the prime minister, who said no one, not even New York governor Franklin Roosevelt, had "shaken hands with the royal body."

In his lively, interested way, Eberhart and I became friends. We missed sharing the same birthday by only a few hours, and we both had strong memories of Cambridge University. I was one of the last in a long line of young poets he had mentored, from Robert Lowell to Allen Ginsberg to 40 years of Dartmouth undergraduates. We talked about putting out a collection of his letters, which would be a fascinating book (Dartmouth's Special Collections is presently processing and cataloging his papers, which will end up running more than 130 linear feet). I showed him my poems, which he treated kindly but honestly. He gave good advice about battling through the vicissitudes of bad luck: His first book of poetry was a single long poem, A Bravery ofEarth, that was published in March 1930, half a year into the Great Depression, and sold only three hundred copies.

Whenever a visit was over, he always tried to drive me back to campus. He loved to drive, and because he was a bit lazy, he would always drive rather than take the three- or four-minute walk to Sanborn House. "I've the blood pressure of a 19-year-old," he would say.

Maine, unexpectedly, was where I communed with Eberhart after I graduated. When I met my future wife, I began joining her family on their annual sojourn on an obscure part of Penobscot Bay called Cape Rosier. This was Eberhart territory. His salt-water farmhouse, Undercliff, was only a foggy cove away from that he steered, like any self-respecting Maine boater, standing up. But most of the time he sat quietly in a weathered Adirondack chair, a pipe on one armrest and binoculars on the other, nothing to read, nothing to do but sit and stare and think. ours. He loved Maine intensely and spent three months at Undercliff every summer. He often flew kites or took out the Reve (French for "dream"), a 36-foot skiff

This summer when my wife and I finished packing the station wagon and were about to launch forth on our 13-hour drive from Washington, D.C., to Cape Rosier, we read out loud "Going to Maine," Eberhart's paean to anticipation from his 29th and final book of poetry, Maine Poems (1989). One afternoon a few days later we kayaked past Undercliff.

When I saw his empty Adirondack chair, I imagined a wisp of pipesmoke curling into the spruce trees and thr rolling words of "Cover Me Over."

The poem, as he predicted, has finally outlasted Richard Eberhart. It will outlast us all:

Cover me over, clover Cover me over, grass. The mellow day is over And there is night to pass.

Green arms about my head, Green fingers on my hands. Earth has no quieter bed In all her quiet lands.

Well Versed Eberhart, relaxing in 1979, was one of the "last remaining links with the heroic age of modern poetry," according to The New York Sun.

When he was 16 he wrote four poems one night after reading Tennyson.

JAMES ZUG is the author of American Traveler: The Life and Adventures of John Ledyard, published this past April and now ina second printing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

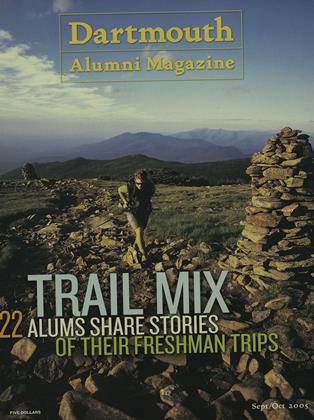

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

September | October 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

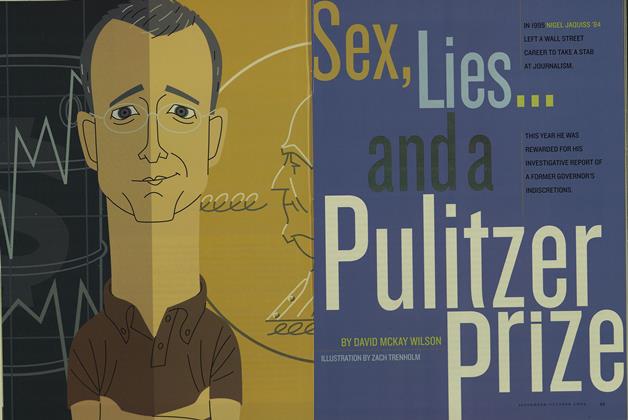

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

September | October 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

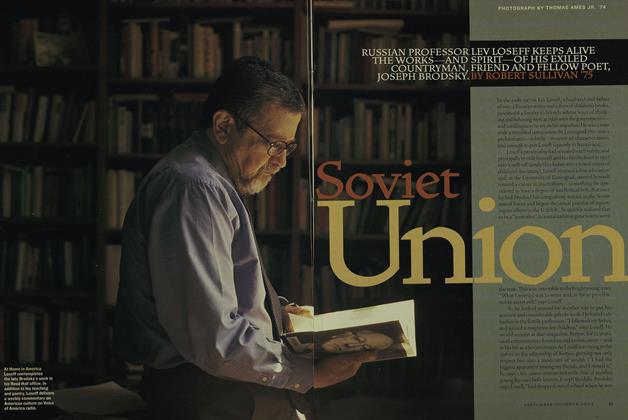

FeatureSoviet Union

September | October 2005 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBand of Sisters

September | October 2005 By Maura Kelly ’96 -

Interview

InterviewThe Archivist

September | October 2005 By Sue DuBois ’05 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2005 By BONNIE BARBER

James Zug ’91

-

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionIn Praise of Class Notes

May/June 2004 By James Zug ’91 -

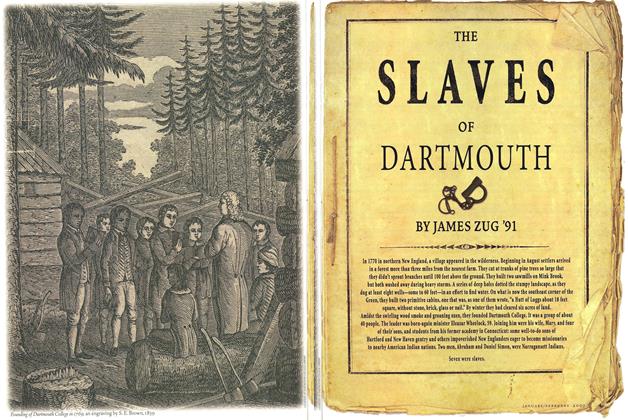

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Slaves of Dartmouth

Jan/Feb 2007 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Article

ArticlePress On

MARCH | APRIL By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYKing of the Hill

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2016 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

pursuits

pursuitsPuzzle Master

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By James Zug ’91 -

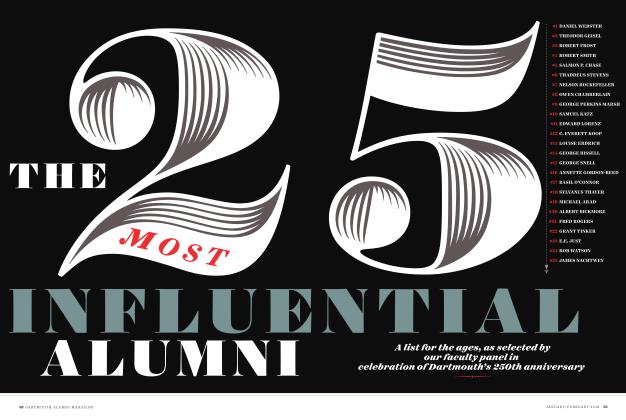

The 25 Most Influential Alumni

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2019 By Rick Beyer ’78, George M. Spencer, Jim Collins ’84, 3 more ...

TRIBUTE

-

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEStories in Stone

May/June 2005 By Andy Rowles ’65 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

Nov/Dec 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEA Life Well Lived

Jan/Feb 2011 By Deborah Schupack ’84 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEChristian Existentialist

Nov/Dec 2007 By Jeffrey Hart ’51 -

TRIBUTE

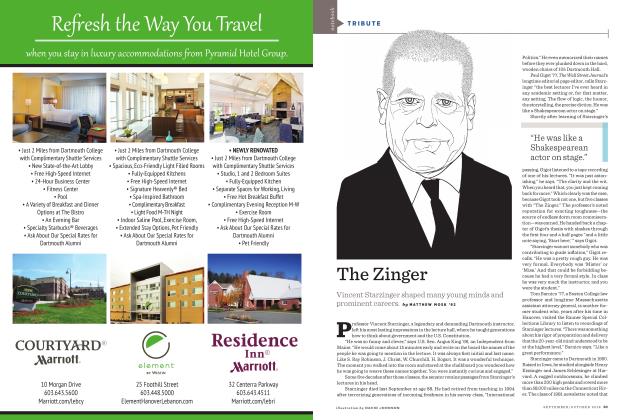

TRIBUTEThe Zinger

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTESage on Stage

Mar/Apr 2008 By Mike O’Connell ’65