Training For Life

A former varsity rower reflects on lessons learned that have little to do with academic studies.

Sept/Oct 2005 Justin Jones ’02A former varsity rower reflects on lessons learned that have little to do with academic studies.

Sept/Oct 2005 Justin Jones ’02A former varsity rower reflects on lessons learned that have little to do with academic studies.

WITHIN 30 HOURS OF GRADUATING from Dartmouth in 2002 I was rowing on the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, training to make the U.S. National Team. The sun seemed hotter, the river dirtier and the air heavier, but I did not allow myself the luxury of nostalgia for Dartmouth. The Connecticut River was behind me; the winding path to the 2004 Olympic Games lay ahead.

Along the watery road to Olympic trials, I would gamer a gold medal at the 2003 Pan American Games as well as a gold and a bronze medal in the elite events at the U.S. Rowing National Championships. At Olympic trials in June 2004 I raced in the double for a place on the Olympic team, but did not earn the honor of representing the United States—and Dartmouth—in Athens. That is where my rowing story ended, but I'll probably reflect more on where it began: the fall of 1998, the moment I arrived for a crew meeting in the Alumni Gym.

"There is no best time, there is only this time," Will Scoggins, my freshman coach, used to say. He would sit on the edge of a chair, finger his gray-flecked beard and survey his young athletes with searching blue eyes. We gathered for practice as we would before a storyteller, and opened ourselves to his vision of who we were to become. We trained not to become athletes, but to become heroes.

In the winter months we converted the bays of the boathouse into a makeshift training facility. We battled on the rowing machines and weight-trained with ancient, rusting equipment. The fun was in "going after it," Scoggins would say, and go after it we did. Amid the clamor of teammates singing along with the music and cheering each other on came the primal shouts of young men challenging their limits.

We would help each other to find the animal within: the moment when absolute focus on getting one more repetition or one more seat in a boat race elevated the mind beyond the pain, the noise and the fatigue. There was a surreal slowing of time as the self and the action became one. If we were to win against the larger, more experienced crews, we would have to row harder, a little crazier.

We discovered that each rower's perseverance solidified the foundation of sacrifice, unity and trust essential for the unique demands of the sport. Many times I would have rested had it not been for the dedication of my teammates.

Training through the long New Hampshire winters prepared us for moments such as those we encountered at Henley-on-Thames in England on Sunday, July 8, 2001, 600 yards into the 1-mile, 550-yard course of the Henley Royal Regatta.

Princeton was a three-quarters boat-length up on us. I was in the stern of the Dartmouth boat, and was aware that our opportunity, our championship, was slipping away from us. After a brief moment of doubt I drove my legs harder against the boat, hanging my weight on the oar.

Steadily our boat locked into one surging rhythm. Eight bodies moved in perfect harmony, the coxswain the unifying consciousness. One mile into the race, we were still half a boat-length down to Princeton. We pulled for our coach Scott Armstrong, for each other, for Dartmouth and for all the training and missed opportunities.

Enveloped in the deafening roar from the grandstand, we charged to the finish line at 42 strokes per minute, edging Princeton by 3 yards. We were the first Dartmouth crew to win this event classified for elite collegiate and club eights. We were the 2001 Ladies' Challenge Plate Champions.

I wouldn't fully appreciate that moment—the joy of sharing the victory with my teammates—until getting to the U.S. National Team Training Center, where the fierce competition would make a team sport feel more like an individual pursuit.

Like my peers at Dartmouth, I had many classrooms beyond the lecture halls and libraries. One such classroom was the stadium. I ran stairs to get stronger, to test myself, but, mainly, because I could.

One such evening was a cold Saturday in early November. A spotlight on the south side of the Davis Varsity House faintly outlined the bench-seats ascending toward the starlit sky. I tested my traction on the ice-glazed bench, and then I was off. The rhythmic, hammering ping of my feet striking the aluminum benchseats echoed off the far side of the stadium, mixing curiously with the muffled music and cheers from nearby fraternities.

Time passed as frost slowly gathered on the inside collar of my thermal shirt. I pounded up the benches several more times. The last run up—No. 67 for the evening—l concentrated on the fleeting seats. Then I was finished, alone with my rushing breath, overlooking the half-sleeping campus, appreciative of the many lives one can lead there. The possibilities were enough to make Dartmouth special—a place where sky-soaring bonfires could happen—and did.

That night in the stadium I turned on numb, slightly quaking legs and slowly descended the stairs. Class was dismissed for the evening.

I had hammered away into the midnight hours on many occasions, and no one had ever stopped me. Even as a sophomore, I knew I would miss Dartmouth—a place where it was okay to be a little mad.

Made in the Shades Jones (center)practices in a Dartmouth shell on theConnecticut River in 2002.

JUSTIN JONES recently completed survivalschool after a hiking trip to New Zealand.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

September | October 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

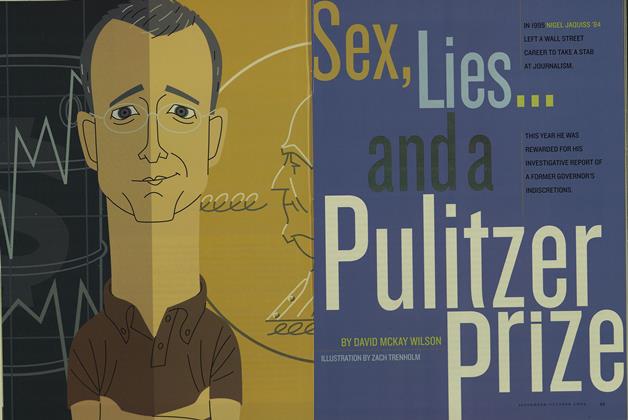

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

September | October 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

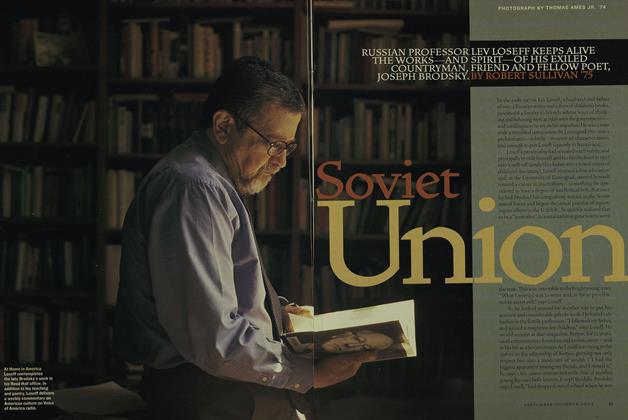

FeatureSoviet Union

September | October 2005 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBand of Sisters

September | October 2005 By Maura Kelly ’96 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTENo Quieter Bed

September | October 2005 By James Zug ’91 -

Interview

InterviewThe Archivist

September | October 2005 By Sue DuBois ’05