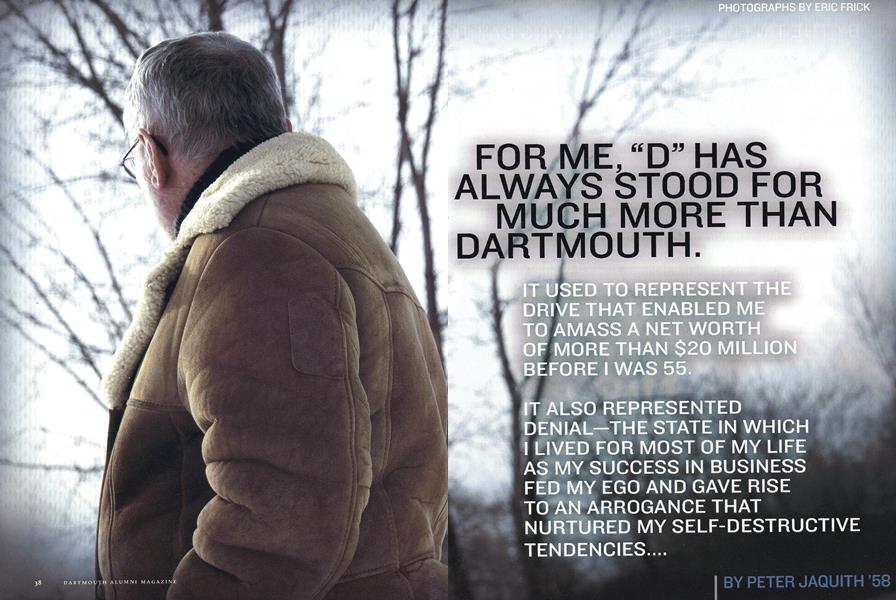

“D” is for Denial

For me, “D” has always stood for much more than Dartmouth.

Mar/Apr 2006 PETER JAQUITH ’58For me, “D” has always stood for much more than Dartmouth.

Mar/Apr 2006 PETER JAQUITH ’58IT USED TO REPRESENT THE DRIVE THAT ENABLED ME TO AMASS A NET WORTH OF MORE THAN $20 MILLION BEFORE I WAS 55.

BY THE TIME I WAS 60 I WAS LIVING DAY TO

I have been sober for eight years. Shortly before I entered a rehab program in 1997 that was to prove successful, I broke down and, for the first time in 50 years, cried uncontrollably for 20 minutes. Afterwards I felt as if a tremendous load had been lifted from me. It was cathartic.

I have an incurable and terminal disease. I have chosen to write bout it in the hope that any reader who suffers from the same disease, directly or indirectly, will gain hope that the inevitable can be postponed indefinitely. Make no mistake: This disease kills. In my years of sobriety I have lost friends and acquaintances to stroke, heart or liver failure, suicides and accidents resulting from addiction. I am not the first alcoholic to matriculate at Dartmouth, nor will I be the last. I have learned that sharing my experiences with others may or may not help them but will definitely help me. I have learned that carrying the message will keep me sober. I am thank- ful to be alive to tell it and to recount the salvation that has come with finally being comfortable in my own skin.

I ARRIVED IN HANOVER IN SEPTEMBER 1954, having received my admission letter in July after anxious months of being wait-listed. My father and uncle were both alums, and my godfather was my fathers Harvard Law School roommate John Sloan Dicke'29, then president of the College. I had graduated from Andover and applied to no other colleges. My tardy acceptance made me wonder if I could keep up with my Dartmouth classmates, and my concern was reinforced when Stearns Morse, the dean of freshmen, informed me I wasn't smart enough to do well in my studies. (He had received a letter from an alum who happened to teach at Andover.)

Upon hearing the deans assessment I decided not to waste too much effort studying. I escaped into a life of partying—and turned the opinion of the dean into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

It took me six years to graduate from Dartmouth because I skipped classes, did little homework, rarely studied and wasted a wonderful opportunity to increase my knowledge and abilities to think and grow. With my self-esteem diminishing daily and feeling isolated from my classmates, I became an alcoholic while seeking "higher" education. This had nothing to do with Dartmouth. It had everything to do with my own makeup.

As a scholarship student I worked evenings in the dining hall, which required me to remain on campus after final exams my sophomore year. My duties involved serving meals to alumni and graduating seniors' parents—and serving beverages to alumni and parents. Late one night during this service I found myself in need of a toilet but chose instead to relieve myself in some bushes near a dark comer of a dormitory. While doing so I was tapped on the shoulder by a campus security officer, who arrested me. At home later that summer I received a letter from the College advising me I would not be allowed to return for my junior year. I had a very low GPAand a few warnings for various infractions. The public urination incident was the last straw. It was suggested that I work for a year or two or fulfill my impending military duty and then reapply for admission if I so chose.

After considering my options, I chose the military and volunteered to join the Army. When I completed my military service I returned to Hanover in the fall of 1958. The College informed me that one more warning in my file would mean automatic dismissal.

The following March a fraternity brother and I decided to hitch a ride to visit girlfriends at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. After returning our dates to their dorms by midnight curfew, we decided to hitch a ride to Amherst to spend the night with a friend of mine at the DEKE house there. Neither of us was familiar with the campus, but the confidence gained through several hours of drinking led us in the right direction. Upon spotting the DEKE house, where I had been once a year earlier, we discovered the door was locked and the lights were off. We realized then that Amherst was on spring break. Undaunted, we kicked in a window and entered the house. After climbing three flights of stairs I opened a bedroom door to discover a white-haired lady asleep in her bed. Only then did we realize we were in the wrong house. As I turned to head down the stairs, I heard a bottle clanking past me, my fraternity brother having dropped his beer. Almost immediately the lights went on. Followed by my friend, I raced through the broken window, severely cutting my leg on a shard of glass. At the hospital emergency room, alerted by a police broadcast, the doctor turned us in and we became guests of the Northampton County jail.

Because this incident occurred outside the State of New Hampshire, I hoped the school would not learn about it. The next day I posted bail, leaving my friend in the cell, and went looking for his date of the prior evening to borrow money to spring him. She told me my friend and I were all over the national news—for breaking into Emily Dickinsons Homestead. Little did I realize how often I would be called upon to explain this incident throughout my professional life: when I sought admission to the New York Bar Association, when I was made a partner at Lazard Freres—and in subsequent job interviews. It lives on as a constant embarrassment.

Somehow, I managed to remain a student at Dartmouth. I graduated at or very near the bottom of my class in 1960.

The day after graduation I reported to my new boss at the Maxwell House division of General Foods Corp. in Minneapolis. My starting salary was $4,800 with the perk of a company car. I worked for the company for one year, during which I totaled two such cars b y driving under the influence through stop signs.

The following year I voluntarily left General Foods to go to the University of Minnesota Law School, where I had qualified as a state resident with good LSAT scores. Within a few weeks I realized that I had discovered my passion. I was an honor student, an associate editor of the law review my third year and graduated cum laude. After graduation I moved to New York City to become an associate attorney at Shearman & Sterling, then the largest law firm on Wall Street. I passed the New York bar and began a career as a corporate lawyer, practicing law for seven years before joining one of my clients, Lazard Freres & Cos., as an investment banker.

Within two years of my arrival there I was made a general partner—in an unusual way. I was called into the office of Wall Street legend and senior partner Andre Meyer, who was seated with Felix Rohatyn, himself a budding legend at the firm. Meyer advised me that Rohatyn needed an aide de camp to manage his schedule and told me that filling this need was the firms most pressing and important concern. Meyer said they both wanted me for the job and, if I did it well, I would become a general partner at the end of the year. I asked Meyer if I could have some time to think about it and he agreed. After briefly considering his offer, I told Meyer that since this assignment was of such great import to the firm, if he made me a partner immediately I would be delighted to assume those responsibilities. Meyer flew into a rage and dismissed me, but the next morning he agreed to my terms.

I remained a partner for the next 13 years, during which Rohatyn and I pursued mergers, acquisitions and corporate restructurings. Working primarily with Fortune 100 firms, we handled friendly negotiated mergers and were very active in hostile takeovers. We were very successful. I was earning about $3 million a year. I owned three homes and rented a New York City apartment. I was known for flying a group of 40 friends to Palm Springs each Thanksgiving.

Throughout those years of challenges and success I was a practicing alcoholic living in deep denial about my disease. I tried to hide my alcoholism from my business associates by not drinking during business hours or in front of my associates. But when I left Lazard to accommodate my wife's wish to live in California, it overtook me. Even so I functioned as a special partner with Forstmann Little & Cos. for a year, then spent two years as an executive director at Bear Stearns. I had not yet learned that alcoholism is one of the only terminal diseases that requires its victims to self-diagnose and accept it; that unless an alcoholic is willing to acknowledge his condition, he will not seek recovery. Alcoholism is an allergy of the body as well as an obsession of the mind. It is a progressive dis ease that worsens with age. The disease is cunning, baffling and powerful. It allowed me to rationalize that I couldn't possibly be an alcoholic given my business success.

At age 55 I was back in Manhattan running my own brokerage business and going through my second divorce. The fact that I was a blackout drinker, that I drank every night and during the day on weekends and holidays, that I drank for the effect alcohol created in me, was totally lost on me. I told myself I could stop if I wanted to. My failure to understand my alcoholism led me to another addiction: crack cocaine. I was introduced to the drug by a young woman I met in a bar. I'd never experienced such pleasure before. Immediately I craved it constantly. Within two years of finding drugs I was broke—but not just because of my $300-a-day habit.

Adivorce court in California had awarded my second wife all of my assets. Ours had become a New York/California commuter marriage in which we had drifted apart as I became a hostage to alcohol, but I didn't anticipate that the judge would give her everything I had. The judge's decision was aided in part because I was too broke to fly to California to attend the divorce hearing and had no representation. I did receive the lease obligation on our modest East Side New York apartment, its furnishings and all debts incurred during our marriage. My wife received several million dollars in assets. Almost $1 million in debt, I had no income. My bank accounts were closed, and when I attempted to sell my brokerage business to offset some of my losses, my ex-wife refused to sign off on the sale. Even as I became a full-blown crack addict, unable to pay my bills, I managed to continue to purchase drugs for my habit by selling crystal pieces left in my apartment to a second-hand store. As I sank deeper into my addiction I pretended to myself that I had no worries in the world. Eventually the sheriff arrived one winter day to evict me from my apartment—giving me two hours to collect my things and leave. I had to take the few clothes I could carry out to the street and join the homeless. An acquaintance put me on to an apartment in Queens where I could live without anyone knowing. It was empty but for one lawn chair, and had neither electricity nor heat, but I was grateful to have a roof over my head.

Because I was deeply medicated by drugs I did not feel the severty of my circumstances. It wasn't until several months later—when I awoke one morning underneath a table in the lobby of the Marrott Hotel on Lexington and 48th Street, where I had crashed the previous evening, and crawled out only to see people in the lobby beautifully dressed for Easter Sunday—that I knew I had to do something about my situation. I left the lobby, walked a few blocks north to the subway, jumped the turnstile (I had no money) and rode to my Queens abode. In a moment of clarity, using the Yellow Pages, I called Seafield, a rehab center in West- hampton, New York, and made an appoint- ment for the following Tuesday—the earliest time available. I still had an insurance poli- cy from the brokerage business that would pay the bill. On Tuesday a Seafield van picked me up in Manhattan and took me to the center. I spent fourweeks there learning about my problem. I arrived accepting I was a drug addict, but I left still in denial, think- ing the only reason I couldn't drink was be- cause it would lead me back to drugs.

Upon my departure from Seafield my younger daughter, Pamela, offered me a bed- room in her apartment in Studio City, Cal- ifornia. She and her sister arranged my transportation, met me at the airport in Los Angeles and took me home. Two weeks later I found my own apartment nearby and moved into it with donated furniture.

Thus began my final fall. Within six months of becoming sober I relapsed. Dur- ing my brief fling at sobriety I had focused on the differences between me and other re- covering alcoholics instead of the similari- ties. The more I emphasized how different we were, the more arrogant and critical I be- came. I now know that these were telltale signs of a relapse, but I didn't see that then. Instead, I wondered who these recovering alcoholics were to tell me how to live.

Even as I found an attorney to pursue an appeal of my divorce decree, confident the appeal would succeed, I slipped back into my disease. Once again I became an around-the-clock crack addict, the only dif- ference being my address. I was a practicing drug addict for the next 13 months.

After being evicted for the second time in my life, in early 1997,1 moved into a drug dealer s home in Northridge, California. I lived with him, his porno queen girlfriend, a cou- ple of "home-boys" and another addict. I purposely lost touch with my daughters and siblings, who assumed I had died. When I lost my divorce-decree appeal—on the grounds that I had thumbed my nose at the lower court by failing to appear—I was stunned.

Almost simultaneously, events in my life conspired to put me on a recovery track. A friend and fellow crack addict named Felicia wanted to leave Los Angeles and return to her family in Mobile, Alabama. She asked me to drive her home and I agreed, despite having no money. She claimed she had all we need- Ed to get us there. After stopping at her drug dealers to replenish her supply, we left Los Angeles at midnight with me detoxing at the wheel of a Hertz truck while she hit her crack pipe. During a stop along the way, as I slept, Felicia spent all her money on drugs. She asked me to find someone to wire us gas money. Furious, I found a pay phone and made a few collect calls. An old friend with whom I had worked a fewyears earlier agreed to wire me a few hundred dollars. Once in Mobile I drove directly to the airport, left Felicia with the truck and—using frequent flyer miles remaining from my old life—ob- tained a ticket back to Los Angeles.

My drug dealer met me at LAX and drove me back to his Northridge house.There, a few days later, I was evicted for the third time when the bank foreclosed on my dealer. I next found refuge in the home of another drug dealer, where there was a lot of traffic throughout the day and night. From there I called the friend who had wired the gas mon- ey to me in Mobile. He told me his boss, Harry, someone I had previously helped sub- stantially with his business, wanted to have lunch with me and would send a car to pick me up. Harry felt he owed me, although I nev- er suggested that. During lunch the follow- ing weekl told Harry that I was ready to come in from the cold. He hired me as a consultant to complete a project for his company and paid me $lO,OOO up front. Within two weeks I spent it all on drugs. Harry quickly figured out that I was still an addict— and made arrangements to put me in rehab immediately.

After three weeks in that rehab program Harry sent me to a residential facility in Pasadena, California, run by the Episcopal church. I told the priest in charge that I ex- pected to stay 30 days of the six-week pro- gram. I stayed seven months. That home saved my life. I arrived weighing 132 pounds and left weighing about 190. Harry had giv- en me a consulting job that provided me with sufficient income to meet my obli- gations. I was able to purchase a car and slowly to do the work necessary to abate my addiction. I had come to understand that I would never be cured of my disease. I grew to understand how it had affected me over the years: Before going out for cocktails or dinner I would have a few drinks at home. When I got home after an evening out drink- ing I would have one or more nightcaps. Whenever I drank at home I drank alone. As I look back at this pattern of behavior from a perspective of sobriety, I see it as insanity.

I lived in Pasadena for six years and had manyjobs. Harry paid me fortwo years, then I had great difficulty finding work. Although I sent out dozens of resumes to companies all over the world, I received no responses. Unable to get back into the business world, I took a job with a Hollywood messenger service. One day I found myself delivering an envelope for an office next to the one I had rented for six years in Century City. I wor- ried about meeting someone I knew on the elevator or in the halls. It occurred to me that God had a sense of humor.

Next I tried telemarketing for a firm in Orange County. I was a salesperson for Sears' kitchen cabinet refacing, traveling an average of 200 miles a day to meet ap- pointments in the greater L.A. area. In all of these endeavors I had to use my own vehi- cle and pay the gas and maintenance bills. I was desperate to become self-supporting. When I fell short I had to ask my family for help. It was deeply humbling, and I devel- oped a great appreciation for people who have no opportunity for business careers and survive through these difficult jobs.

As I was sinking into a depressed state I was contacted by a reporter from The NewYork Times who had heard about my situa- tion at a dinner party and tracked me down through one of my old business associates. The call came at a time when I realized my story was my only asset. I was willing to tell it. After the Times reported on my decline in August 2003,1 accepted invitations to appear on the Today show and Oprah. This publicity brought me back into the business world, where I am now trying once again to make a living. I realize now that had my ex-wife not been awarded virtually all my money I would have used it to kill myself through my addiction.

I'm grateful for the court's decision and truly believe God intervened to save my life. My spiritual life sustains me, as do the close relationships I have established with my daughters, Ann '87 and Pamela. While sober I have been blessed with four grandsons, two of them named for me, who have never seen their grandfather take a drink or a drug.

I hope they never will.

Peter Jaquith, photographed in Rochester, New York, December 14, 2005.

PETER JAQUITH lives in Rochester, NewYork.He is working on an autobiography. This is his firstpublished work.

DAY WITH A DRUG DEALER, HOOKED 24/7 ONCRACK COCAINE AND UNABLE TOUNDERSTAND HOW I HAD LOST EVERYTHINGI HAD WORKED FOR—AS WELL ASMY DIGNITY AND SELF-ESTEEM.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMind Matters

March | April 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2006 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2006 By Paul Stone '60 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Stages of Life

March | April 2006 By Nell Shanahan ’99 -

Sports

SportsThree Times a Coach

March | April 2006 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

March | April 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe 1961 Alumni Awards

July 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobert Lincoln O'Brien 1891

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

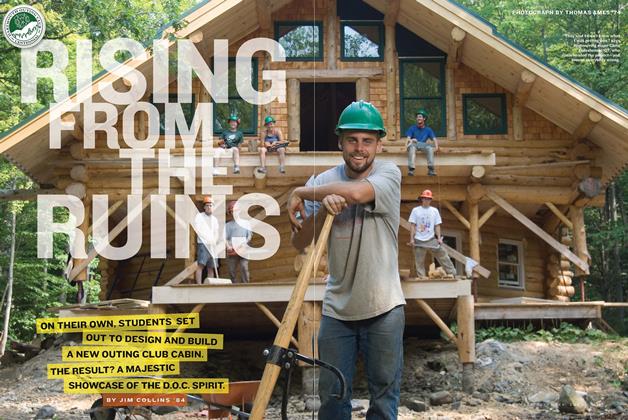

FeatureRising From the Ruins

Nov/Dec 2009 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

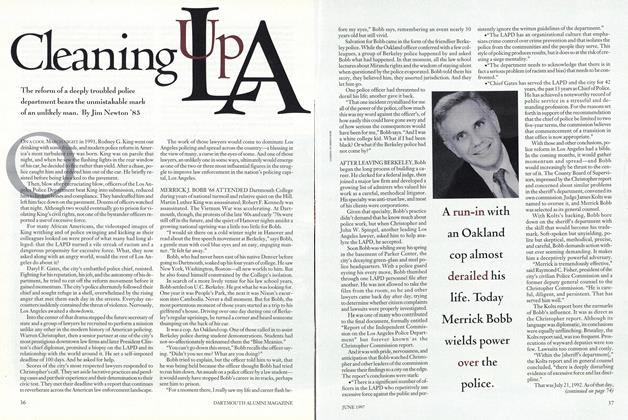

FeatureCleaning Up La

JUNE 1997 By Jim Newton '85 -

Feature

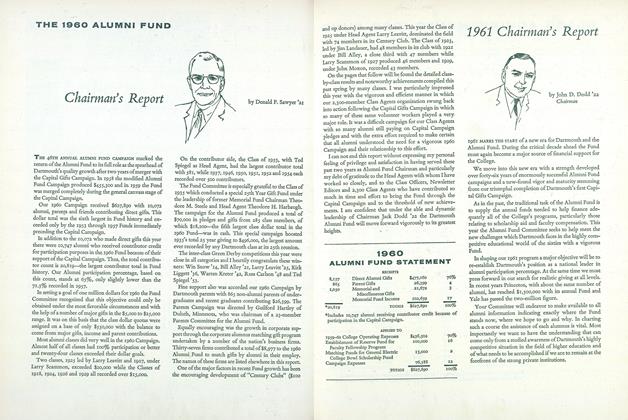

Feature1961 Chairman's Report

December 1960 By John D. Dodd '22 -

Feature

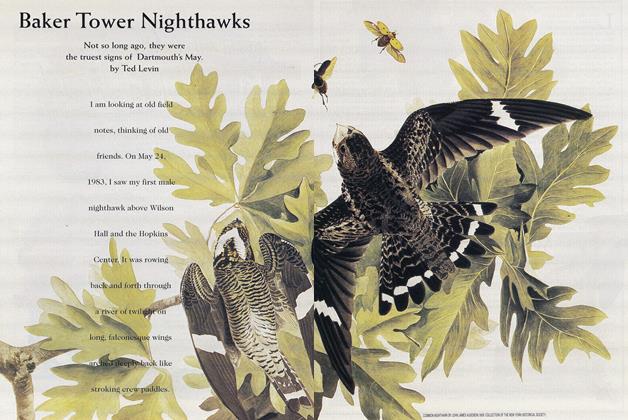

FeatureBaker Tower Nighthawks

May 1994 By Ted Levin