Myths of Innovation

Two Tuck professors explore how entrepreneurship succeeds—and fails—in large companies.

Mar/Apr 2006 Vijay Govindarajan and Chris TrimbleTwo Tuck professors explore how entrepreneurship succeeds—and fails—in large companies.

Mar/Apr 2006 Vijay Govindarajan and Chris TrimbleTwo Tuck professors explore how entrepreneurship succeeds—and fails—in large companies.

IT'S CLEAR TO US FROM years of observation that large companies generally fail to realize their full innovation capacity. It's no accident that business icons such as Bill Gates and Michael Dell have achieved success by starting their own ventures.

Five years ago we set out to conduct in-depth studies of new business launches at several well-known corporations including Corning, Hasbro, Analog Devices and The New York Times Co.This was a great deal of fun. The people we spoke with had been through the most compelling experiences of their business lives. They described exhilarating highs and excruciating lows. They enlightened us on the many trials and tragedies that make entrepreneurship within large organizations a unique challenge. No two companies that we examined used the same approach to building a new business within an existing one. There are few commonly accepted practices. In part, this is because the science of innovation is barely under way. Because of the lack of any proven discipline for new business building, stories of innovation remain highly influential. The most common goes something like this:

It was the best of times for the Mammoth Corp. Earnings were growing year in, year out.

targets. Mammoth was humbled. But one day Mammoth was late on a product launch. The company ceded a huge chunk of market share to a younger and hungrier competitor. At the end of the quarter the company missed its earnings

The leadership team quickly rose to the challenge of restoring Mammoths glory. The CEO made a big speech and sent the word out to all employees that Mammoth was looking for the Next Big Idea.

The company held innovation seminars, innovation workshops and innovation retreats to catalyze the search. Then came the magic the company was looking for: From a dark and forgotten corner deep within Mammoth there emerged a visionary—our hero—a leader with the Next Big Idea.

Mammoths executives were careful, but after much deliberation they concluded that this indeed was the Next Big Idea. And so our hero landed a dream job, leading Mammoth into the future.

But it wasn't as easy as all that. Our hero discovered the truth about big organizations—that they are machines built to excel at yesterdays business. Our hero ran into roadblocks: people who demanded that he honor procedure; people who stood in the way of smart hires; people who insisted that the business would fail unless it adopted more of Mammoths best practices. Within a few months, inspiration became desperation.

Late one night our hero woke up in a cold sweat. In a dream he had been wrestled into submission—and nearly strangled to death—by a giant octopus.The significance of the dream was obvious. Our hero resolved right then and there that he would defeat the octopus, using whatever means necessary. Mammoth would not be allowed to destroy its own future.

In the real world the myth of the innovator vs. the octopus is worse than just amusing fantasy. It is destructive. There are two flaws. First, the story suggests that the big idea is all you need, when in fact the big idea is just the be ginning. Second, the story suggests that a lone rebel can convert the idea into aviable new business. In truth, even the most talented leader cannot succeed alone. Innovation requires more than just individual achievement—it requires organizational excellence.

We propose a new innovation myth in which our hero is not a rebel but a wise and experienced conductor of a symphony of business activity. Our hero views competitors as enemies, not insiders. Our hero knows that winning is a matter of orchestrating the construction of something entirely new, something that can evolve quickly and something that can benefit from limited, targeted engagements with the existing band of talented musicians.

Our hero would achieve harmony by meeting the three fundamental challenges unique to entrepreneurship within large organizations: forgetting, borrowing and learning.

FORGETTING: NewCo's business model is invariably different from CoreCos. The answers to the most fundamental business questions—who is the customer? what value do we offer? how do we deliver it?—are dramatically different. The essence of the forgetting challenge is ensuring that CoreCo's success formula is not imported to NewCo. Forgetting is much more difficult than it sounds, because there are so many reinforcers of the behaviors that have made CoreCo successful. To forget, NewCo must be built from scratch, with no preconceived notions about hiring (in particular, both outsiders and insiders should be considered), organizational structure, core processes, performance measures or values.

BORROWING: NewCo's biggest advantage over its competition is the wealth of resources and assets within CoreCo. The essence of the borrowing challenge is gaining access to these resources, and doing so in away that is healthy for both NewCo and CoreCo. Borrowing is always in tension with forgetting, because the most certain way to forget is to completely isolate NewCo from CoreCo. Thus, NewCo should only borrow where it can gain a crucial competitive advantage, never just for incremental cost cutting. Links between NewCo and CoreCo inevitably create tensions. A top priority for the senior management team is to ensure that interactions remain healthy and productive.

LEARNING: NewCo's business is highly uncertain. It must systematically resolve the specific unknowns within its approach as quickly as possible, and zero in on the best possible approach. Unfortunately, the typical planning process for corporations is designed for something entirely different—holding managers accountable to known standards. NewCo must operate on a separate and distinct planning cycle, one optimized for rapid learning rather than consistent performance.

When it comes to innovation, individual entrepreneurs capture our imagination but established organizations have the greatest untapped potential. When large companies master the challenges of forgetting, borrowing and learning, they still may fail to dazzle, but they will certainly prosper.

VLJAY GOYINDARAJAN, recently namedone of the world's 50 most influential management gurus by the London Times, and CHRIS TRIMBLE are on the faculty at theTuck School of Business at Dartmouth. Theyare the authors of the book Ten Rules For Strategic Innovators: From Idea to Execution (Harvard Business School Press,December 200s), from which this article wasadapted.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

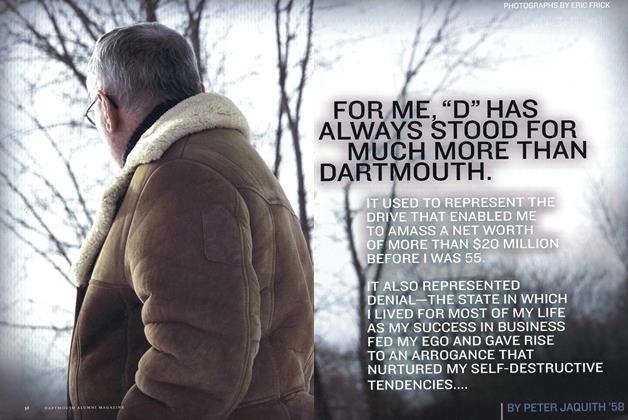

Feature“D” is for Denial

March | April 2006 By PETER JAQUITH ’58 -

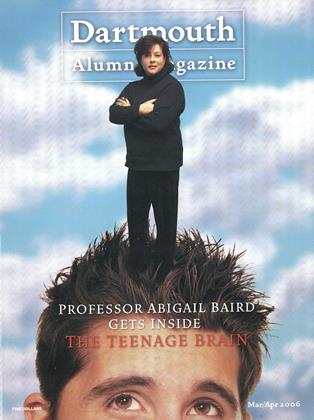

Cover Story

Cover StoryMind Matters

March | April 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2006 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2006 By Paul Stone '60 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Stages of Life

March | April 2006 By Nell Shanahan ’99 -

Sports

SportsThree Times a Coach

March | April 2006 By Brad Parks ’96

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONThe Perils of Innovation

Nov/Dec 2010 By Chris Trimble and Vijay Govindarajan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Well-Traveled Story

July/Aug 2009 By Ernest Hebert -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Next Frontier

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jay C. Buckey Jr. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAmerica Is Queer

Sept/Oct 2011 By Michael Bronski -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionDouble Trouble?

May/June 2001 By Ronald M. Green -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionCan You Believe It?

May/June 2004 By Walter Sinnott-Armstrong