Eyes Wide Shut

When corporate prestige breeds overconfidence, good managers may find themselves in denial over major business problems.

Sept/Oct 2003 Sydney FinkelsteinWhen corporate prestige breeds overconfidence, good managers may find themselves in denial over major business problems.

Sept/Oct 2003 Sydney FinkelsteinWhen corporate prestige breeds overconfidence, good managers may find themselves in denial over major business problems. By Sydney Finkelstein

People have been shaking their heads recently over the Jayson Blair reporting scandal at The New York Times. How could top management have let it go on for so long? How could they have missed all the warning signs? One staffer was even quoted as saying, "How could we be so stupid?"

But it's not stupidity at all. In fact, what happened to The Times is not very different from what happened to Barings Bank in the Nicholas Leeson scandal or to Motorola when it watched passively while the cell phone business shifted from analog to digital technology. In my research I've found that companies led by very smart executives fall into disastrous situations, and the same patterns emerge time after time, across industries.

Despite what most people might think, in almost every case of major corporate failure, key executives are fully aware of what's going wrong, in real time. At Barings Bank, Nicholas Leeson was covering up huge losses on his speculative trades by relying on Account #88888 as a catch-all clearing account to make sure the numbers balanced. Far from being a "rogue" trader, however, Leeson had approval from his superiors in London. Even among clerks in the Singapore office where Leeson held court, interviewees told me that his activities were an open secret.

Similarly at The Times, the management knew that Jayson Blair's stories had to be corrected dozens of times. Metro editor Jonathan Landman e-mailed superiors that, "We have to stop Jayson from writing for The Times. Right now." That was more than a year ago. Senioreditors were aware of Blair's track record. And reports are emerging that several of Blair's former colleagues had strong suspicions about his activities. In short, Blair's untrust worthiness was an open secret when the scandal broke, and many in the organization were not surprised at all.

Another shocking pattern is that in case after case, senior executives who know that something is wrong specifically choose not to do anything about it. At Motorola, a succession of CEOs watched as Nokia took market share away with its new digital phones. Remarkably, Motorola owned several key digital patents that it licensed to Nokia, which then had to report back how many digital phones it was selling. Yet despite this detailed market information, Motorola executives chose not to enter the digital market themselves, which would have meant turning away from their dominance in the analog market.

At The Times, top management has pleaded guilty to poor internal communication, but the story goes deeper than that. Top editors who knew of problems with Blair's work intentionally did not share that information with other editors. Instead, Blair was assigned to the highpressure national desk. Even when he wrote front-page stories that relied on unnamed: sources and drew complaints, senior editors kept him on the job and did little to rein him in.

The big question is why. How could executives at prestigious institutions such as Barings, Motorola and The Times fail to act in the face of such clear data? I believe that fundamentally it's not about incompetence or poor communications or a diversity program that got out of hand. The key is in the very prestige that these companies enjoy.

The Times is internationally respected by outsiders and revered by insiders. It considers itself not just Americas newspaper of record, but maybe even the best news organization on the planet. When your aspiration is to be not just great but the best, it's easy to believe that your young reporter has actually scooped everyone else on the Washington sniper story or the Jessica Lynch story. Why question someone who is simply fulfilling the organizations highest selfimage? Blair appeared to be doing the kind of reporting that was expected of him.

It's the same at many other blue-chip companies: Leaders choose not to sweat the small stuff because they've been so successful for so long, they disregard warnings that would trouble a less confident group. The willingness to challenge the status quo and confront dominant but dangerous assumptions are the hallmarks of thriving companies. When these qualities are absent, even smart executives fail.

When Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger puts the blame squarely on Blair, he is factually correct. Blair is the one who lied, cheated and plagiarized. But it appears Sulzberger doesn't realize that, from a management perspective, this was much more than a case of poor internal communications or a flawed mentoring process for young reporters. It's about leaders closing their eyes to reality in the face of evidence that challenges their deepest self-image.

Sydney Finkelstein, author of Why Smart Executives Fail (Portfolio), is a professor at the Amos Tuck School of Business.Reprinted from The Wall Street Journal 2003 DOW Jones & Co. Inc. All rights reserved.

In case after case, xecutives who know something is wrong thoose not to do anything about it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

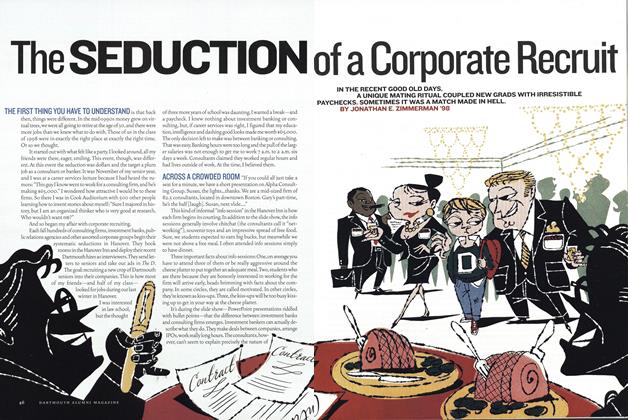

FeatureThe Seduction of a Corporate Recruit

September | October 2003 By JONATHAN E. ZIMMERMAN ’98 -

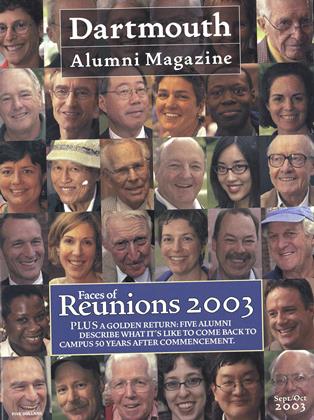

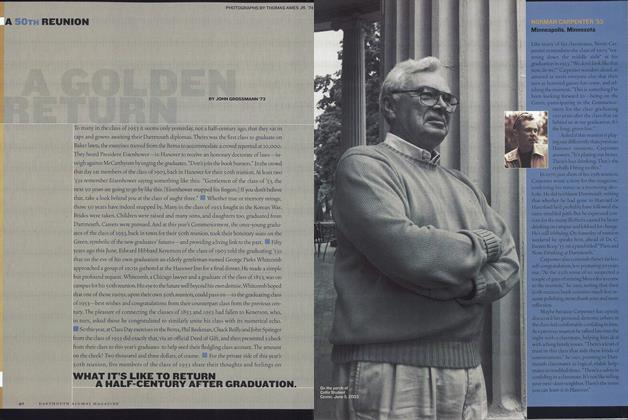

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Golden Return

September | October 2003 By JOHN GROSSMAN ’73 -

Feature

FeatureO Julie!

September | October 2003 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

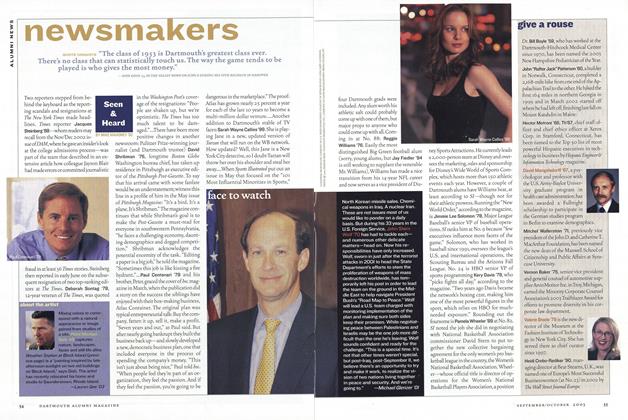

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

September | October 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Outside

OutsideGetting the Ax

September | October 2003 By Lisa Gosseling -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionLet the Hype Begin!

September | October 2003 By Kabir Sehgal ’05

Faculty Opinion

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMillennial Mindset

May/June 2007 By Aine Donovan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTrain The Brain

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By CECILIA GAPOSCHKIN -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Global Classroom

May/June 2003 By Jack Shepherd -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Next Frontier

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jay C. Buckey Jr. -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July/August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionDouble Trouble?

May/June 2001 By Ronald M. Green