Investor’s Ed

Investing retirement funds should require a license—just as driving does—to prevent financial crashes.

Nov/Dec 2006 Annamaria Lusardi and Alberto AlesinaInvesting retirement funds should require a license—just as driving does—to prevent financial crashes.

Nov/Dec 2006 Annamaria Lusardi and Alberto AlesinaInvesting retirement funds should require a license—just as driving does—to prevent financial crashes.

INCREASINGLY, INDIVIDUALS IN THE United States are in charge of their financial well-being before and after retirement. This is fundamentally a good idea. It is a basic principle of liberal philosophy that people should be in charge of their own lives, and that includes saving for retirement and investing their retirement wealth. It's also a good idea because the financial distress of pay-as-you-go public pension schemes will make it more and more difficult for governments to support their citizens' retirements.

Large companies have already shed traditional retirement plans and turned to 401k programs. Congress just passed a bill that allows companies to switch workers over to 401k plans. However, too little attention is paid to the fact that successfully investing for retirement requires financial knowledge and competence, and financial mistakes may not only harm the people who make them, but society as a whole. For example, a completely clueless investor may ruin himself and his family financially, ending up elderly and poor. He will also impose a cost on society since some form of financial support will eventually be provided by taxpayers. Society has an interest in helping individuals make good investment decisions.

The risk is real since financial ignorance is rampant. Evidence from a major U.S. survey—the Health and Retirement Study (HRS)—shows that about half of older Americans do not understand the concept of compound interest and the effects of inflation. An even larger percentage does not know that investing in a single stock is riskier than investing in a diversified mutual fund. These mistakes are often compounded by peer effects: Many people follow their friends' advice in financial matters.

A recent study in a leading financial journal shows that church attendance, a social activity, leads to a larger propensity to own stocks. Fellow churchgoers like to dispense financial advice, and people listen to them. Even professors and teachers do not seem to display much financial dexterity. Evidence from a randomly selected sample of TIAA-CREF participants during the 1990s shows that half of investors from academic institutions had not changed their asset allocation once over a 10-year period. While fluctuations in stock market prices require reallocation in the composition of the portfolio to keep the desired ratio of bonds and stocks, many investors rarely make any changes.

When left to their own retirement saving and investment decisions, people may simply postpone the decision until it is too late. A striking finding from the HRS is that lack of planning and lack of knowledge about pension rules is widespread among American workers. The fact that one third of workers 50 and older have not thought at all about retirement is not a good sign, since not planning is tantamount to not saving. Lack of preparedness is also apparent from how little current workers know about Social Security and pensions. Not only are most workers incorrect about the age at which they will be eligible for Social Security benefits, but about half of the older workers surveyed in the HRS do not even know which type of pensions they have.

How do economies implement a system where workers are in charge? People will only buy into it if they can benefit from it. Perhaps we could learn about steering our financial futures from driving schools, where the goal is to prepare drivers to obtain their licenses. Why do we require drivers to have a license? First, we want to be sure they know the rules of the road and have basic driving skills. Second, knowledge and skills related to safe driving will decrease the chance that they will do harm to themselves and others. Like a clueless investor, a reckless driver hurts himself,his family and society as awhole.

A financial drivers license issued by each state would not cost much and does not need to be another large public program. In fact, it could be administered via a Web page and be based on standardized tests. One does not need to be a financial wizard to manage his savings, just as a driver does not need to be a mechanic or a Formula 1 racer to be out on the road. With the same amount of time required to prepare for a driving test, investors could learn some basic information that could prevent horrible mistakes. Rather than listening to random tips, workers would acquire knowledge about fundamental financial concepts, such as diversifying, exploiting the power of interest compounding and taking advantage of employers' pension matches and tax-favored assets.

People should repeat the test if they fail. They should show their financial licenses to their employers. Employers, in turn, could be required to direct employees without licenses to a default pension plan or to consultations with a certified financial planner. Acquiring competence and financial literacy will empowerworkers and help them appreciate the potential advantages of an ownership society. Ask yourself: If you weren't required to obtain a drivers license, would you take the time to read your states driving manual before hitting the road? Maybe.

But getting financial information is a bit trickier. We do not have a state or national standard for financial literacy, or an official manual one can read to gain basic financial information. A financial license will address these deficiencies too.

Will financial drivers licenses solve all the problems? No. Drivers licenses can't prevent all accidents. We have already agreed that the benefits of being able to drive with a license outweigh the risks of the road. We are willing to limit the risk on the roads because we recognize the danger to individuals and to society. We should take the same measures to reduce the risk on household balance sheets.

ANNAMARIA LUSARDI is a Dartmouthprofessor ofeconomics. ALBERTO ALESINA is professor of economics at Harvard.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

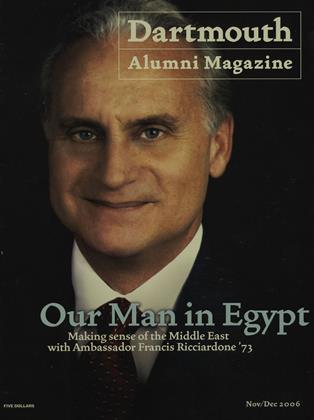

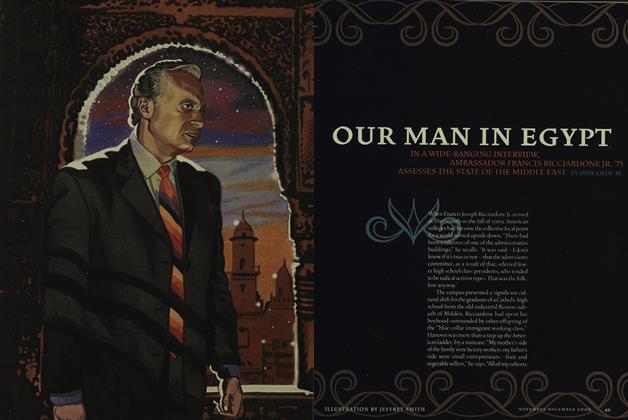

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

November | December 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

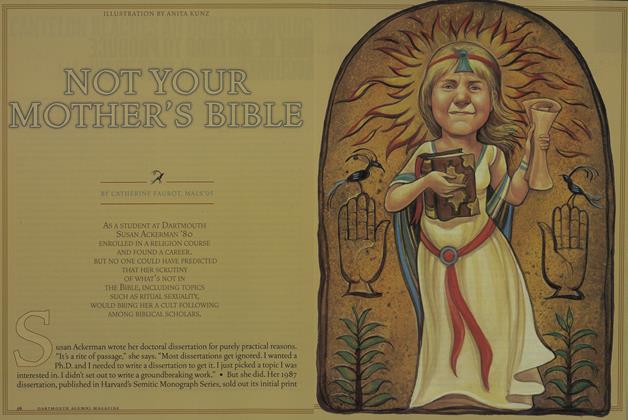

FeatureNot Your Mother’s Bible

November | December 2006 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’05 -

Feature

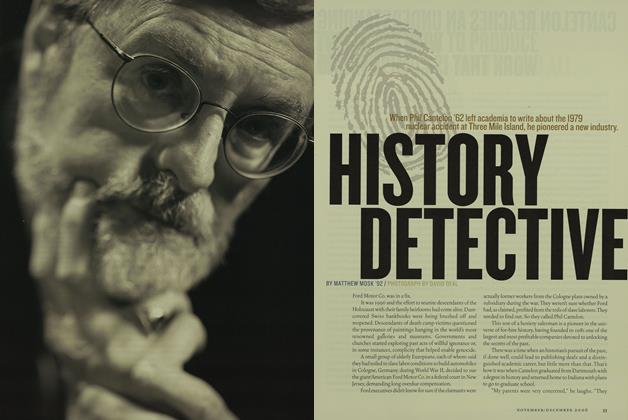

FeatureHistory Detective

November | December 2006 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONFailing the Test

November | December 2006 By John Merrow ’63 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSReturn of Pinto

November | December 2006 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Sports

SportsTips of the Trade

November | December 2006 By Courtney Banghart ’00

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMillennial Mindset

May/June 2007 By Aine Donovan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTrain The Brain

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By CECILIA GAPOSCHKIN -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Well-Traveled Story

July/Aug 2009 By Ernest Hebert -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Global Classroom

May/June 2003 By Jack Shepherd -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONThe Ultimate 24 Hours

MAY | JUNE 2014 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionEyes Wide Shut

Sept/Oct 2003 By Sydney Finkelstein