Can You Believe It?

An atheist explains why he can’t buy into religious thought—and ponders the damage done by some who do.

May/June 2004 Walter Sinnott-ArmstrongAn atheist explains why he can’t buy into religious thought—and ponders the damage done by some who do.

May/June 2004 Walter Sinnott-ArmstrongAn atheist explains why he can't buy into religious thought- and ponders the damage done by some who do.

I RECENTLY VISITED A TOP PREP school with my teenage daughter. In front of all the visitors, the principal proudly announced that his school is open to all religious views. As evidence, he reported that his students are about 40 percent Catholic, 40 percent Protestant and 15 percent Jewish, with the remainder believing in various other religions, including Buddhism. He didn't even mention atheism, presumably because he doesn't take atheism to be a significant position on religious issues. Another possibility is that none of his students are atheists, but that's unlikely. Many of my students and colleagues at Dartmouth who are atheists now were already atheists in high school. Or maybe the atheists at this prep school hide their views from their principal and their parents, so there are many more atheists than meet the eye.

Why would atheists hide? Many avoid religion because they find it boring or they dislike being hounded by evan- gelicals. Atheists don't want to spend their lives talking about God any more than they want to spend their lives talking about UFOs or the Loch Ness Monster. For such myths, their motto is, "Get over it!" Another reason is that criticism of re- ligious beliefs is often considered impolite or even unconstitutional—although it isn't. Religion is treated like a senile relative whose bizarre statements are not to be questioned.

courage to admit that you are an atheist. There is also a darker side to atheists' silence: Atheists fear that their views will alienate friends and family, clients and employers. Preachers often proclaim that among atheists, "Everything is permitted" Who would want to befriend or hire or vote for anyone with no morals? Although very few atheists really believe that everything is permitted, as long as this parody of atheism is widespread, it takes

Atheists need to display such courage and honestly explain why they do not believe in God. The explanation is simple. Most educated modem adults don't believe in ghosts for the same reasons: We have no real evidence for ghosts. Even people who think they see a ghost should acknowledge that their apparent evidence is extremely dubious. Moreover, we have evidence against ghosts, since ghosts are incompatible with established science. These same problems arise for religious beliefs. There is no good evidence for God and much evidence against God. Yet many intelligent people, including many of the faculty at Dartmouth, believe in some form of deity. Why?

Some religious believers claim to have evidence for the existence of God, but religious experiences are no more evidence for God than ghost experiences are for ghosts. Both kinds of experiences arise in circumstances —such as high emotionthat make them unreliable. Reports of miracles are no better, since supposed witnesses have strong motives to lie or deceive themselves. We would never accept such testimony in court. And philosophical arguments for God—ontological, cosmological and teleological—have been refuted many times. When surveyed impartially, every educated modern adult should agree that there is no good reason to believe in God.

Without reason, faith still might seem defensible. However, mere faith is irresponsible when it conflicts with the evidence. Traditional religious beliefs do conflict with lots of evidence, particularly the widespread suffering in this world. Many children have been born with horrible birth defects that caused them tremendous pain and early death. An all-good God would prevent these harms if he could. An all-powerful God could prevent them. It follows that there is no God who is both all-good and all-powerful, as traditional Judaism, Christianity and Islam claim.

why do we need so much, and why must it be distributed so unevenly? In the end, there is no way around this and other evidence against the existence of any traditional God. Theologians give many responses, but they all fail under scrutiny. Maybe God repaid the child's suffering with a ticket to heaven, but why didn't God send him straight to heaven without the suffering? Maybe free will is more important than any amount of suffering, but what does free will have to do with birth defects? Maybe God was teaching a lesson to the child's parents, but isn't it unfair to use one person's suffering to teach others, especially when you could use better teaching methods? Maybe we mere mortals are too feeble and ignorant to see the justification for suffering, but then why should we believe there is any justi- fication? Maybe God is not subject to our lowly human moral standards, but then why should we love or worship such a God, except out of fear or confusion? Maybe we need some suffering to make us appreciate the good things in life, but

Perhaps we should let people believe what they want, no matter how silly, as long as they don't hurt anybody. But religious beliefs do hurt people by caus- ing wars. Many wars, of course, are not based on religion, and even religious wars result from non-religious forces as well. Nonetheless, it is hard to deny that many wars from the Crusades to the modern day have been and continue to be fueled in large part by religious beliefs. It is no coincidence that terrorists are so often motivated by religion, since it is harder to get non-religious people to volunteer as suicide bombers.

Religious beliefs have also motivated attacks on homosexuals and abortion doctors. They create conflicts within and between families. Organized religious lobbies slow medical progress in important areas such as stem-cell research, which almost nobody opposes except on religious grounds. Paralyzed people confront the costs of religious beliefs every day. So do parents of children with juvenile diabetes and children of parents with Parkinsons or Alzheimer's. Stemcell research might not succeed in curing all of these ills, but surely it should be tried.

Finally, religion does theoretical damage. It is amazing what intelligent people can bring themselves to believe in the name of religion. The only way they could get themselves to accept such beliefs is by intentionally ignoring the evidence. How could theists stop this self-deception from infecting other parts of their intellectual lives?

I admit that religion has some personal benefits for some believers: It helps many people get through their daily lives. It also motivates some people to help others. But that is sad. If people cannot face their lives without illusions, and if they are not motivated to help others apart from the commands of a fictional God, then we are all in deep trouble.

Of course, when I am teaching, I do not force my atheistic views on vulnerable students. I present both sides as fairly as I can, and I encourage students to think about the issues for themselves. Still, I wonder whether it might be better to teach the truth. Professors don't put up with beliefs in ghosts, even in student papers. Why should we have to treat religion differently?

Outside of classes, most atheists see little to be gained by broadcasting their beliefs. Theists won't listen, and atheists don't need to listen. This defeatist attitude means that evangelicals get away with spouting harmful nonsense. They gain confidence, and many undecided people with open minds hear only one side of this important issue. If atheists let themselves be cowed, our countiy's policies will continue to be distorted by ancient religious myths. More religious wars will arise. And there will be more suffering among people who need abortions or stem-cell treatments or just sexual freedom.

Our best hope for progress is for atheists to speak out and, as politely as possible, tell any theists who will listen why religious beliefs are indefensible.

WALTER SINNOTT-ARMSTRONG is aprofessor of philosophy and the Hardy Professor of Legal Studies, as well as co-author of God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist (Oxford University Press).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May | June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

Feature

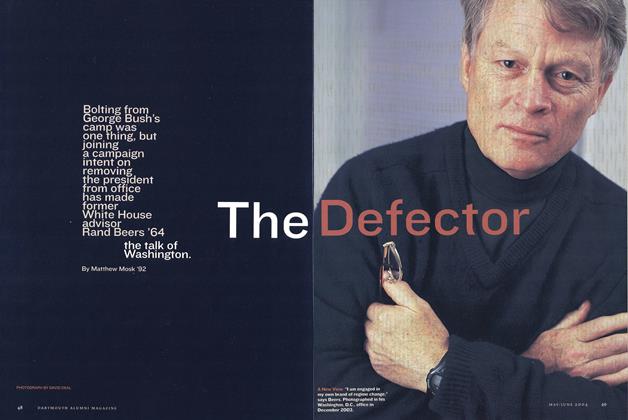

FeatureThe Defector

May | June 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May | June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

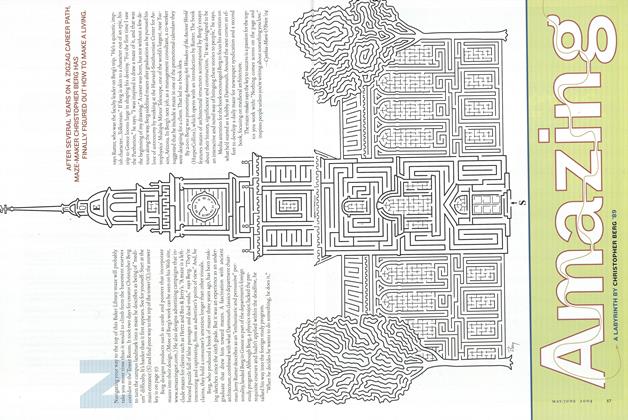

FeatureAmazing

May | June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Sports

SportsStraight Shooter

May | June 2004 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71

Walter Sinnott-Armstrong

Faculty Opinion

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMillennial Mindset

May/June 2007 By Aine Donovan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTo Be a Lazy European

Jan/Feb 2007 By Bruce Sacerdote ’90 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTrain The Brain

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By CECILIA GAPOSCHKIN -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionPatriotism’s Perils

Jan/Feb 2003 By JAMES BERNARD MURPHY -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July/August 2006 By Lucas Swaine -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionEyes Wide Shut

Sept/Oct 2003 By Sydney Finkelstein