Crossroads of the East

As China expands its economy and military, the United States needs to pay more attention to the region.

May/June 2008 DAVID KANGAs China expands its economy and military, the United States needs to pay more attention to the region.

May/June 2008 DAVID KANGAs China expands its economy and military, the United States needs to pay more attention to the region

HOW TO DEAL WITH CHINA'S RAPID EMERGENCE DURING THE PAST 30 years as a global power has become a major issue in the United States. Debate over whether to view China as a threat is increasing in Washington, D.C., but so far there is little consensus. The business community is strongly in favor of building durable relations with China, while the military establishment is more skeptical. There are also those who are willing to take a wait-and-see attitude, hoping that in time developments can assuage U.S. fears about future Chinese intentions.

However, threats to the United States from East Asia do not arise from the traditional sources of great power: rivalry and conflict. Rather, the greatest threats to the United States could arise from the actions of the smallest and weakest countries in the region, Taiwan and North Korea. Furthermore, these threats are not direct threats against the United States but instead arise indirectly—from a U.S. decision to defend Taiwan or from the possibility North Korea could sell nuclear weapons to a Middle Eastern terrorist group that would use them against the United States. Aside from these indirect threats, the United States, along with most East Asian countries, faces no direct military threat to its security in the region.

Indeed, U.S. interests there are as much economic as they are military. Economic growth, not military conflict, has been the hallmark of the modern East Asian region, and U.S. economic ties to the region are deep and growing deeper. The United States has traditionally interacted with East Asia through a series of bilateral security arrangements, known as the "hub and spoke" model. When U.S. power was at its height during the Cold War this strategy was largely successful at promoting U.S. interests and fostering growth and stability in the region. Now, however, this strategy is under increasing strain. While relations with Japan have grown closer, U.S. bilateral security arrangements with the Republic of Korea are in the process of evolving or being scaled back. At the same time the rise of regional multilateral cooperative institutions, while hardly in a position to replace the role of the United States, is creating alternate pathways to cooperation. Combined with Chinas rise and increasingly active diplomacy, the United States is most often in the position of reacting to—rather than leading—changes in East Asia.

Despite its deep ties to the region, however, the United States is a global power with regional interests. The United States is only intermittently attentive to the region; Washington often deems problems elsewhere in the world as more important than issues in East Asia. It will mainly intervene in the region when it is in its interest to do so. The United States remains by far the most powerful and im- portant country in the world, and all East Asian states would like to see more, not less, American attention to the region, even if they also know they cannot rely on or expect unequivocal U.S. support. Still, most of the states welcome or accept U.S. leadership and are satisfied with the status quo: a U.S. military presence that is not unduly intrusive along with stable economic relations with China.

To that end, the United States faces a difficult path in the future. It can try to remain the most important and influential country in the region, but this will require more sustained attention to the region and a more equal relationship with many countries than has been the case in the past. Or the United States can allow East Asian cooperation to develop, with it occasionally being included and occasionally being absent. How U.S. policy develops will have key implications for stability in the region. If the United States and China ultimately yiew each other as a threat and begin to balance each other militarily, the region as a whole will become increasingly unstable. Yet if the two great powers find a modus vivendi, even if that is not outright partnership, the region will more likely be stable.

In fact, there is little debate in East Asia about whether China is a threat. East Asian states see substantially greater economic opportunity than military threat in China, and therefore accept, rather than fear, Chinas expected emergence as a powerful and perhaps dominant state in the region.They prefer China to be strong rather than weak, and although the states of East Asia do not unequivocally welcome China in all areas, they are willing to defer judgment about what China wants. Historically, it has been Chinese weakness that led to chaos in East Asia. When China is strong and stable, order has been preserved.

What might be China's goals and beliefs a generation from now is at best a wild guess—so much will change between now and then, within China itself, within the region and around the globe. In 1945 it would have been remarkable to think that 30 years into the future the United States would be withdrawing from Vietnam, that China would be not only communist but lost in the throes of a decade-long "Cultural Revolution," or that South Korea would grow to become the nth-largest economy in the world. In 1975 most observers thought the United States and Soviet Union would be locked in rivalry well into the next century, and would have scoffed at the notion that China could manage an economic transformation that would dwarf South Koreas. Thus, we cannot predict how East Asia will evolve during the next generation.

The United States has generally viewed its foreign policy and grand strategy as global, whether during the Cold War or now in its fight against terrorism. Yet most politics are more local than global. The United States has also not been very good at understanding the nuance and complexity of the diverse regions in which it has interests. China's rise in East Asia has global implications, to be sure. Yet perhaps more importantly, the East Asian region has its own internal dynamics, shared history, culture and interactions—many of which occur without any regard for the larger world and many of which are not well understood by Americans. To argue that a regional view of Chinas rise is critical does not mean that the search for basic, underlying factors is futile or that social science cannot illuminate important issues in East Asia. Quite the opposite: How China and the East Asian region evolve in the coming generation will have a major impact on regional and global relations. If all sides manage their relations with care, the future has the potential to be more peaceful, more prosperous and more stable than the past.

All East Asian states would like to see more, not less, American attention to the region.

DAVID KANG is a government professor andan adjunct professor at Tuck. This is adapted fromhis most recent book, China Rising (ColumbiaPress, 2007).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

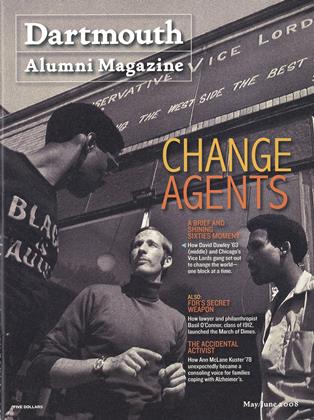

Cover Story

Cover Story“We Could Change the World”

May | June 2008 By E.J. CRAWFORD -

Feature

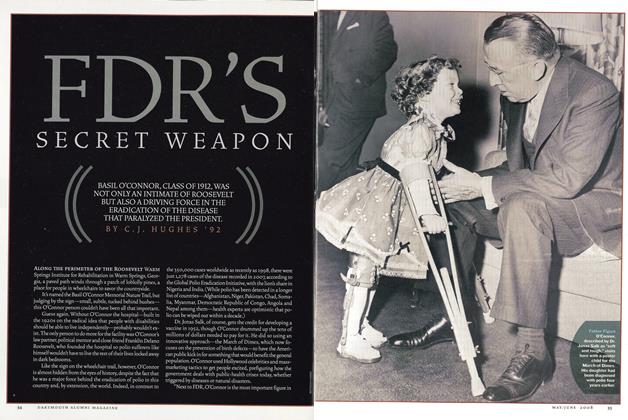

FeatureFDR’s Secret Weapon

May | June 2008 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

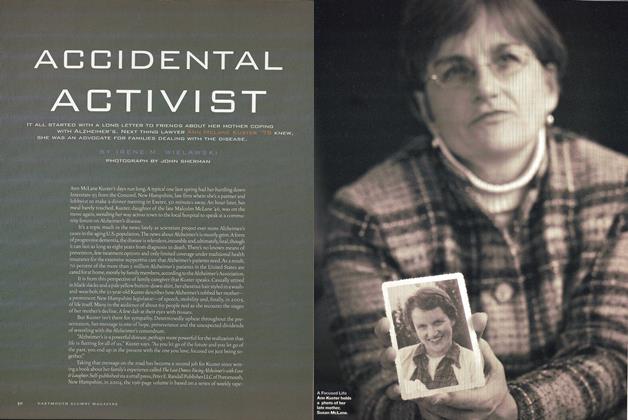

FeatureAccidental Activist

May | June 2008 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2008 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2008 By Kit Wilson '89 -

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May | June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONInvestor’s Ed

Nov/Dec 2006 By Annamaria Lusardi and Alberto Alesina -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTo Be a Lazy European

Jan/Feb 2007 By Bruce Sacerdote ’90 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTrain The Brain

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By CECILIA GAPOSCHKIN -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONLive Free or Die?

Jan/Feb 2009 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAmerica Is Queer

Sept/Oct 2011 By Michael Bronski -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONDesigner Genes

Mar/Apr 2008 By Ronald M. Green