Band of Brothers

They bonded during the tumultuous 1960s while fighting for change on campus. And they’ve remained a tight-knit group ever since.

Sept/Oct 2006 RALPH WIMBISHThey bonded during the tumultuous 1960s while fighting for change on campus. And they’ve remained a tight-knit group ever since.

Sept/Oct 2006 RALPH WIMBISHTHEY BONDED DURING THE TUMULTUOUS 1960s WHILE FIGHTING FOR CHANGE CAMPUS. AND THEY'VE A TIGHT-KNIT GROUP EVER SINCE,

FOR THEM, IT SEEMS LIKE A LIFETIME AGO. IN THE FALL of 1966 seven spirited young men arrived in Hanover with their eyes ablaze, just as America was catching fire. And they helped change the face of Dartmouth—at a time when it needed a good I kick in the butt.

This band of soul brothers from the class of 1970 was spurred on by the "We Shall Overcome" battle cry of the 1960s and the angry voices of Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown and the late Malcolm X—all the while marching in step to a Miles Davis beat. In retrospect, some in Dartmouth circles saw this Band of Brothers, as they call themselves, as a bunch of bad-ass Ivy League militants who wore Army jackets instead of green blazers. In fact, they evolved into a group of smart, cool professionals who have spent the past 40 years putting a cerebral exclamation point on the term "black power."

"One thing remarkable was that we wanted to learn everything. We just wanted to know it all. We were so thirsty for knowledge," says Wallace Ford '70, one of the 18 black freshmen who came to Hanover that fall, bringing the enrollment of minority students to about 30.

Ford and his freshman buddies—Don Dayson, now an internist in New York; Dandre DeSandies, a therapist at Stanford's counseling and psychological services center; Keith Jackson, a San Diego real estate developer; Herschel Johnson, writer and poet; Larry Stephens, a corporate lawyer with Sony Pictures Entertainment in California; and Tom Walker, a Chicago contruction management consultant—supplied the mind and muscle needed to make the Dartmouth Afro-American Society a force on campus by raising the significance of black consciousness. In the process, they made the most of their educational opportunities and left their marks in places far beyond Hanover.

"We had a commitment to excellence," says Ford, who went on to Harvard law school, public service and business consulting before authoring two novels. "It wasn't just about trying to see how much hell we could raise. We became dear friends, like brothers, in the classic sense of the term." Truly, this was a curious bunch.

Johnson, the writer, poet and artist, was the spiritual heart of the group. He came from "Bomb-ingham," Alabama, and knew the families of the four little girls killed in the 1963 church bombing. "Herschel always had a lot on his mind," says Walker, his college roommate. "He was very thoughtful, sometimes pensive, always searching for a better way to express himself. He dabbled in painting and drawing, but writing was the thing he focused on."

Walker, a high school football player with an imposing presence from Corpus Christi, Texas, was such a stabilizing force that his nickname was "Peace." "He was tall, good-looking and athletic," says Stephens, "a role model of what a strong black man should be."

Stephens (pronounced "Stef-fens") was the jovial Mr. Smooth who, when not singing in the Glee Club, was crooning to the ladies at various get-togethers. "Stevio" had an ear for music and an eye for architecture. "He never got angry," says Jackson. "That was his style."

Jackson, from San Diego, says he grew up in "Ozzie-and-Harriet riet land in black face." A basketball player and good high school athlete, he had a keen entrepreneurial sense. "Keith always was one deal away from the big one," Stephens says. "He was always about making money or chasing down some girl."

And there was Dayson, the "ethereal," soft-spoken doctor-to- be from Brooklyn whose heightened sense of curiosity sent him hitch-hiking all across New England at a time when black faces were rarely seen in rural towns. "I thought he'd be a poet," says Stephens. "You say Don Dayson, I'd say poetry."

"Don was one of the quietest people that I had ever met," Ford says. "He introduced me to aspects of music and literature that I had never known or considered. He moved to his own beat."

Ford moved to a beat of his own. He was a tall, lanky 16-year- old brainiac who became the lightning rod of the group. Born in Harlem, he was the son of a civilian auditor for the U.S. Army. In 1953 the Fords moved to Japan, where young Wally attended local schools and learned to speak fluent Japanese. He started school at age 5 and was bumped up to the second grade two weeks later. Four years later the family moved to Puerto Rico for two years before returning to the United States in 1959. "By the seventh grade, I was just 10 years old," he recalls. "I don't recall anything unique about me except that I really enjoyed reading, enjoyed going to school. I loved to read. My parents, when I was about 9, bought the World Encyclopedia, and I read it in three months."

When the Ford family settled in Teaneck, New Jersey, Wally became friends with DeSandies, a short, skinny kid. You might say that became the core of the Brotherhood, since both were accepted to Dartmouth. But Wally was set on attending Johns Hopkins until his dad, concerned about non-academic distractions, thought otherwise.

"He overheard me talking on the phone about how much fun I was going to have in Baltimore, all those pretty girls at Morgan State and Howard just down the road," Ford says. "He thought the temptations might be too much, so he steered me to Dartmouth." And DeSandies came along for the ride. "Wally's dad took us to Dartmouth in his little Chevy Corvair," he recalls. "I had my little trunk."

Right away, Ford and DeSandies formed friendships that would last forever. "There were so few of us blacks on campus, we came to know each other very quickly," says DeSandies. "The first person I met was Herschel. He was one of the kindest persons I'd ever met. A good brother, he loved to make people happy."

Instinctively, The Brothers enlisted in the Afro-American Society (AAS) and joined forces with upperclassmen such as Will McCurine '69, Woody Lee '68, Bob Bennett '69, George Spivey'68 and Tom Parker '69. Founded in the spring of 1966, the group met weekly to respond to the increased need for black awareness within a Dartmouth community that AAS members considered "foreign."

During the next few years the group worked fervently to increase black enrollment and faculty, make curriculum changes, bring notable black speakers and entertainers to campus and even sponsor a black arts fair. And nobody would have thought that George Wallace would play a major part.

The segregationist former governor of Alabama came to Hanover in the spring of 1967 as a prelude to his 1968 presidential run, and the blacks on campus decided they had to make a statement.

"There was friction around methods to get our point across to the administration and campus community," DeSandies says. "We argued, sometimes vehemently, about how aggressive or gentlemanly we should be." Ultimately, after great debate, they decided to boo Wallace, turn their backs and walk out of Webster Hall in protest. Some cleverly had signs hidden under their jackets.

Here's how Time magazine reported the incident in its May 12, 1967, issue: "With all the venom of a southern mob barring a school door to a Negro child, a handful of northern demonstrators sought last week to deny the Dartmouth College auditorium floor to George Wallace. 'Wallace is a racist, Wallace is a racist!' chanted Negro undergraduates as the Alabamian tried to address the student body. Then, led by a white instructor from Colby Junior College in New London, N.H., who yelled 'Get out of here! Get out of here!' the students charged the stage. Other students blocked the rush while Wallaces bodyguards hustled him to the wings."

Ford remembers things a little differently. "I do not recall anybody jumping up on the stage," he says. "He wasn't booed off the stage. Let's say he may have felt his presence wasn't welcomed."

Forced to cut his speech short, Wallace was escorted out to his limousine, where a handful of loud students, black and white, were waiting for him. They pounced on his car and rocked it back and forth.

"This was before security got good," Ford says. "We didn't think we'd get that close. I remember seeing his face through the rear-view windshield, and he was very unhappy."

The Wallace incident got the message across to everybody in the Dartmouth community, as well as to the nation through network newscasts the following night. The message was, yes, there are black students at Dartmouth, they are part of the institution—and the institution had to change.

"It was a pivotal moment in that it galvanized the movement at Dartmouth," Stephens recalls. "It really brought us together."

In the fall of 1967 The Brothers did more than let their Afros grow. With a new freshman class that included about 25 more blacks such as Charles Johnson '71, La Vergne Randolph '71, Frank Watkins '71 and Thomas Price '71, it was imperative to keep the boat rocking. They challenged the administration to increase recruitment of minority students. In response, The Brothers were authorized by the admissions office to go on speaking tours to various schools around the country.

Not only were these recruiting trips productive, they were fun, too. On one trip to San Diego, Ford and Stephens went out on the town after meeting with some prospective students. When Stephens asked, "Where's the sisters?" somebody directed them to a nearby convent.

Road trips always were special. Somebody would get a car and off they'd go in groups of two or three. Often, they'd speak to other student groups at schools around New England. One favorite destination was Mount Holyoke, where Walker met his future wife, Beverly. Johnson had a steady girl there, too. Her name was Marita.

"When he walked, he strode with comfortably long strides while slightly rolling his shoulders from side to side, not in an affected hustler manner, but in a way that expressed a hip confidence."

Several of The Brothers spent their semesters abroad: Stephens went to France; Dayson went to Tanzania. Some received Tucker fellowships or participated in the A Better Chance program, tutoring or serving in neighborhoods from Jersey City to Mississippi.

InApril 1968 Martin Luther King's assassination provided The Brothers with another defining moment. Ford, a DJ on WDCR, went on the air that night and, with input from Johnson, issued an angry proclamation directed at white America.

"We laid it out there. It was a very, very angry statement written in the height of emotion," Ford recalls. "The man who speaks about nonviolence is killed. We felt terrible about it, felt frustrated by it. Not all of us were fans of Martin Luther King. A lot of black people in 1967,1968 didn't think nonviolence was the way to go. We may have disagreed on his tactics, but not his goals." When Fords attack made it into print, a number of the white students took it personally and began to harass him; some called him the racist.

"I watched his back," Dayson recalls."At a party somebody went after him. Another time somebody threw a coin or something out of a window and it hit him in the head. Wally had a way of saying things to you, and some [white] people didn't like him." Says Stephens: "Wally grew into a fearless leader. He had no fear. He was always a target. He took the heat, and he was brilliant."

The tension continued to mount. In the fall of 1968, after another summer of the Vietnam War and the Bobby Kennedy murder, The Brothers were back on campus, armed with more demands. They didn't take over any buildings as some students did at other campuses, but things began to change. As DAM reported in its May 1969 issue, "Quietly and with no public commotion, a letter from Dartmouth's Afro-American Society landed on the desk of certain administration officers and faculty members on March 4." The letter cited 18 demands (another was added later) and asked the College to respond by April 3. "The official College, from President Dickey down, reacted seriously to the AAS letter," reported DAM. "What ensued was 39 days of intensive, at times physically exhausting review, discussion and formulation among administration, faculty and black students—carried out as Dean Leonard M. Rieser put it, in a climate of urgency in order that there be no sense of emer- gency.'" The administration addressed the need for black faculty, more money was committed to financial aid, and a black-studies program was established as well as the summer Bridge Program, which was created to give remedial help to incoming freshmen.

Culturally, Dartmouth became the place to be. The Alvin Ailey American Dance Company, with Judith Jamison, performed on campus, as did the likes of Ornett Coleman and Sly Stone. Don Cherry, the trumpeter, became an artist in residence. Theatrically, The Brothers convinced the drama department to stage something other than HMS Pinafore. Ford performed in Martin Duberman's documentary play In White America, and Johnson was the lead in Royal Hunt of the Sun, the Peter Shaffer play about the destruction of the Inca empire.

By the spring of 1970 black students had a distinctive voice at the College. That was quite evident after the Afro-American Society went to the administration with one more request: How about a black speaker at commencement? Dean Carroll Brewster came up with the idea of creating "an equal opportunity speaker," and Ford was chosen by his peers.

Ford electrified his audience that day. "The time is coming, the time has got to come, when freedom will be seen in our smiles, and Blackness will mean freedom. We have to believe this, because this is the only reality left to us," he said.

Ford was amplifying his feelings about the black Dartmouth experience. "I wanted to get the message out," Ford recalls. "How we felt about the school, the country, the times—and make that balance. I didn't want to embarrass anybody's parents."

Fittingly, Ford wrapped up his 10-minute address by quoting a poem written by Johnson:

For you with backs achingfrom bending

And flushing and scrubbingFor all of you women on transitYou with brown bags under your armsBringing home the leavings of white folksBringing it to your childrenFor all of you black mothers and fathersWho had to live with humilityAnd yet have the pride to surviveFor you black mothers and fathers who raised usYour men are now with you.

"It was one of those moments when even if you didn't agree with or like me, you couldn't deny the message," Ford says. "Every now and then, you may write something and you hit it, you're on; like when Michael Jordan hit seven 3-pointers in a row That's how I left Dartmouth."

After graduation The Brothers went their separate ways. Though they never had an official reunion, The Brothers remained in touch through good times and bad. Like 10 years ago, when Jackson battled throat cancer and Stephens drove down to San Diego from Los Angeles to make sure he got to radiation therapy.

"When I got tired of taking the pills, Herschel would call me almost every day and tell me it was something I had to do," Jackson says. "He walked me through it all."

Johnson had health problems, too, and one day in the spring of 2005 his heart failed, sending a shockwave through the group. At his funeral on May 6 in New York, The Brothers again came together, this time to say goodbye.

"He was my brother, my soul, a prince among men," Stephens says. "It was so difficult to see him there [in a casket] and not lose it."

Jackson, recovering from a stroke, couldn't make it to New York. "When Wally called with the news, I just wept," he recalls. "I hadn't cried like that since my father died."

Those same eyes that were ablaze in 1966 were all drenched in tears. Yet the funeral was a celebration. There was recorded music, a live jazz performance, singing, poetry, readings from Johnsons work and several testimonials by those who mustered the strength to speak.

The Brothers embraced one another that day and realized just how special they were to one another. Herschel was gone, but not their indomitable spirit.

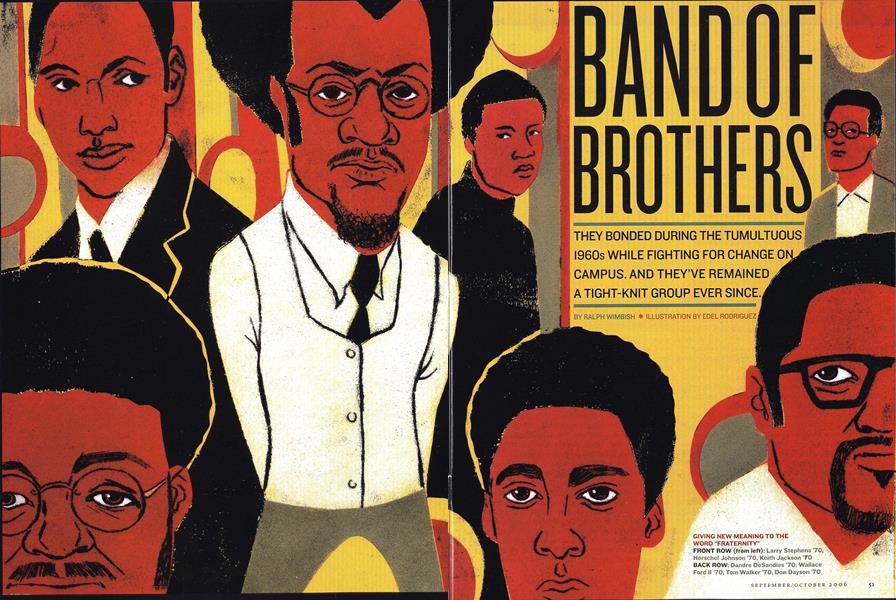

GIVING NEW MEANING TO THEWORD "FRATERNITY" FRONT ROW (from left): Larry Stephens '70. Herschel Johnsop '70, Keith Jackson '70 BACK ROW: Dandre DeSandies '70, Wallace Ford II '70, Tom Walker '70, Don Dayson '70

That Was ThenIn 1969 Dayson (left)and Ford (right) workedas Tucker interns in Jersey City, New Jersey.

This is Now Four of The Brothers gathered with other friends of Herschel Johnson '70 at his May 2005 funeral. From left: Tom Walker '70, Michael Orr '71 , Frank Watkins '71, Charles Johnson '71, Larry Stephens '70, La Vergne Randolph '72, Don Dayson '70, Thomas Price '71 and Wallace Ford II '70—with Wallace Ford III.

"IT WASN'T JUST ABOUT TRYINGWE BECAME DEAR FRIENDS, LIKE BROTHERS TO SEE HOW MUCH HELL WE COULD RAISE. IN THE CLASSIC SENSE OF THE TERM."

"CULTURALLY, DARTMOUTH BECAMECONVINCED THE DRAMA DEPARTMENT TO STAGE THE PLACE TO BE. THE BROTHERS SOMETHING OTHER THAN HMS PINAFORE"

RALPH WIMBISH is assistant sports editor at the New York Post. Heis the co-author of the biography of New York Yankees catcher Elston Howard, Elston and Me: The Story of the First Black Yankee

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

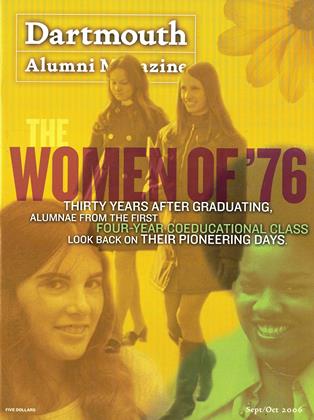

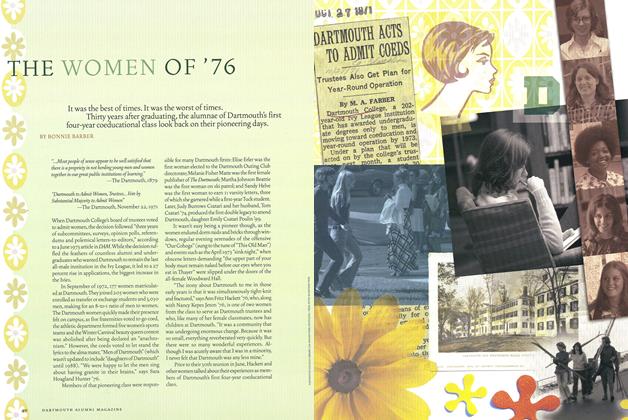

Cover StoryThe Women of ’76

September | October 2006 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

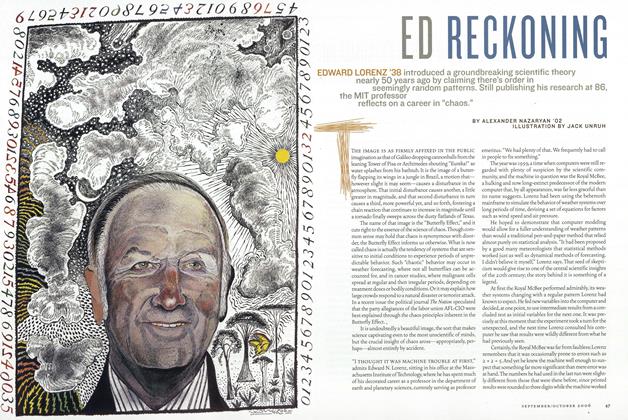

FeatureEd Reckoning

September | October 2006 By ALEXANDER NAZARYAN ’02 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2006 By Russell Hardy' 62 -

Feature

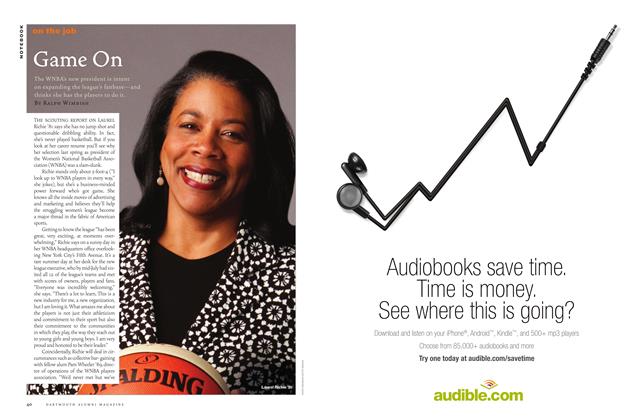

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2006 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SPORTS PUBLICITY -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYHigh Fidelity

September | October 2006 By Brian Corcoran ’88 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONDown the Tubes

September | October 2006 By Melissa Lafsky ’00

RALPH WIMBISH

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Special Teacher

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureKoop

June 1992 By C. Everett Koop '37 -

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

APRIL 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureLAND OF LOVE

MAY 1973 By Ralph J. Fletcher '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth's Ambassadors

OCTOBER 1997 By Simone Swink '98 -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill