The College prepares for the ultimate health emergency— an avian flu pandemic.

FOR DARTMOUTH'S EMERGENCY planners, the avian flu is out there somewhere, moving and growing over a distant horizon, never out of sight. Like a tropical depression in the South Atlantic viewed from a small town in Florida, the threat level is still low but the danger is real. Will it turn into the "big one," a global pandemic to match the Spanish Flu of 1918 that killed more than 50 million people, 675,000 of them in the United States and more than 25 right here on campus?

"When it comes to pandemics, there is no rational basis to believe that the early years of the 21st century will be different than the past," said Mike Leavitt, secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), at a New Hampshire summit conference attended by Dartmouth planners on May 26. "If a pandemic strikes, it will come to New Hampshire."

If that happens, Dartmouth intends to be ready. The pandemic planning group (PPG), a subset of the Colleges standing emergency management group, met in a day-long April retreat to assess the situation. Accenting the gravity and importance of the needed plan, President Jim Wright addressed the group, noting that advance planning was particularly important in a residential community such as Dartmouth.

"This is an extension of our existing capabilities," says Michael Blayney, the Colleges director of environmental health and safety. "We're adding capacity, and this planning process has enhanced our ability to plan for other problems."

Those other problems will have to take a near-term back seat. "If President Wright has to make the call to suspend the academic program and send students home," says Sheila Culbert, senior assistant to the president and chair of the PPG, "it will be one of the toughest decisions in the history of the College. Even in 1918 the College didn't shut down."

The Great Pandemic of 1918 is everyone's worst-case scenario. Between 20 and 40 percent of the worlds population caught the Spanish Flu. People who felt fine in the morning were dead by nightfall. Unlike other flu strains, this one killed young adults even more readily than it did older people—the highest mortality rate was in the 2O-t0-5O age bracket. Dartmouth was no exception. Though an official count doesn't seem to exist, it appears that 25 students and two faculty members died. Among those students, about half were members of a physically fit corps of military cadets in training for service in World War I. Full dormitories are no place for a lethal virus that might selectively target young people, so Dartmouth's best defense is obvious: As the flu approaches, depopulate the campus.

completed or begun work on all 28 items on the list. Heavy reliance will be placed on education and individual planning, beginning with a letter to the Dartmouth community that went out in May outlining the potential problem.

"Students call it 'that really scary letter,' " laughs Linda Kennedy, director of student activities and a member of the PPG. "One of them, after hearing one of my discussions, asked, 'So sometime in the next hundred years this might happen?'" And it's not just students who aren't yet overly concerned. At this year's First Year Parents' Weekend, Kennedy gave a presentation on the threat: Eight people came.

"Education is the critical component," says Culbert. "Pandemic planning will be part of orientation this fall."

Should a worst-case scenario unfold, the Colleges plan calls for a suspension of the academic program and a partial evacuation of the campus. Viruses spread faster in clustered communities of people, and a busy college is a cluster defined. The trick, like the problem faced by evacuation planners monitoring an oncoming hurricane, is when to make the call.

For the College, that call will depend initially on warnings from the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO uses a six-phase system to assess the seriousness of a possible pandemic. Right now the avian flu is in phase three ("No or very limited human-to-human transmission"), the lowest level of an actual alert. If the virus gets to phase six ("Efficient and sustained human-to-human transmission"), if it's of a particular virulence and if it gets close enough to New Hampshire, the College's emergency plan will go into effect. The PPG will then ask the first question: Are the students better off here or somewhere else? Most everyone involved expects the answer to be the latter.

"We've been told to expect near simultaneous worldwide outbreaks," says Kennedy. "We'll close on the early side so that everyone can get into smaller groups. The problem is that we can't force-evacuate 6,000 people. We'll want parents who are close enough to come get their own students. Others we'll take to public transportation hubs, provide them with food, water and money for several days of difficult travel." Initial comments by federal planners had included the probability of restrictions on travel, but authorities have now assured Dartmouth's group that travel away from campus will be possible.

Suspending classes and getting most students off campus will be just the beginning. If the 1918 pandemic is any guide, the flu will come and go in a matter of months. Dartmouth's plan assumes a less-than-one-year disruption in the academic program. All essential staff functions required to keep the College running will have to continue. That means not just facilities management and payroll, but admissions, development, financial administration and many other departments. Although an obvious tool will be an increase in staff telecommuting (and part of the plan is to increase the Colleges already-strong Internet connectivity so that people can work from home), the campus will be far from empty. As just one important example, Blayney points to the Colleges science and technology buildings, all of which house hazardous materials as part of their core mission. "We're responsible for the research community and its facilities," he explains. "So if the College shuts down, we'll effectively become night watchmen."

But the College's core responsibility, of course, is to the health of its people, not its buildings. "We want people to be selfreliant," says Blayney. "For faculty and staff, we want them to begin thinking about their families' needs—food, water and energy for what may be an extended dislocation of the economy. Seventy-two hours of self-sufficiency is the minimum we want people to prepare for."

After that? Like any battle plan, the advance-planning version may be obsolete within a few days of its implementation. The PPG will meet regularly to reassess the situation, but already the College is far ahead of where it was when the Spanish Flu caught the whole world by surprise in 1918 and nobody was sent home from Hanover. In the Rauner Library archives there's a photograph of students and military cadets gathered at the height of the pandemic, doing mass calisthenics on the Green.

"Don't expect that," laughs Culbert, "even if the thing never materializes."

Birds on the Brain The College hopes to avoid scenes such as this one from the 1918 flu outbreak.

ED GRAY is a frequent contributor to DAM. He lives in Lyme, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

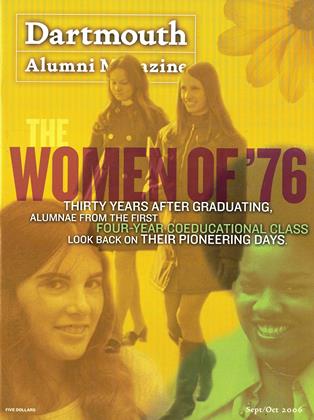

Cover StoryThe Women of ’76

September | October 2006 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

FeatureBand of Brothers

September | October 2006 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

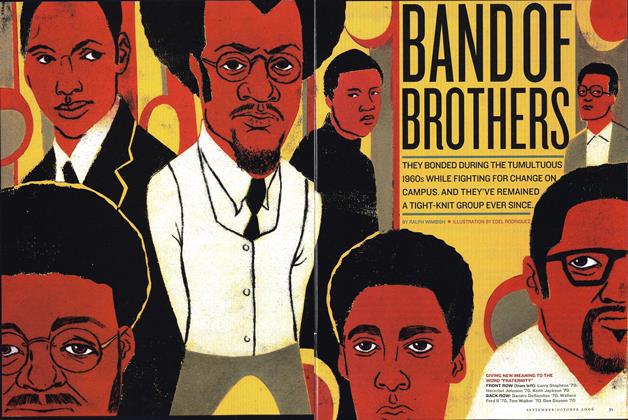

FeatureEd Reckoning

September | October 2006 By ALEXANDER NAZARYAN ’02 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2006 By Russell Hardy' 62 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2006 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SPORTS PUBLICITY -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYHigh Fidelity

September | October 2006 By Brian Corcoran ’88

Article

-

Article

ArticleAnnouncement that Commencement will be held "as usual"

June 1917 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI BARRED FROM CHINNING FRESHMEN

February, 1923 -

Article

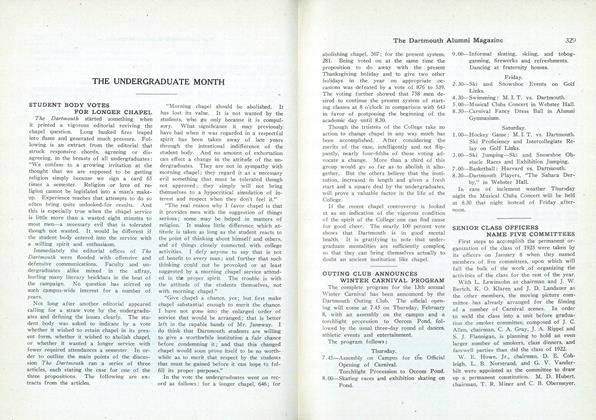

ArticleNew Faculty Members

November, 1930 -

Article

ArticleMASON TROPHY WINNER

May 1962 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

JANUARY 1968 -

Article

ArticleST. LOUIS ASSOCIATION

June, 1926 By Charles W. Mckenzie '20