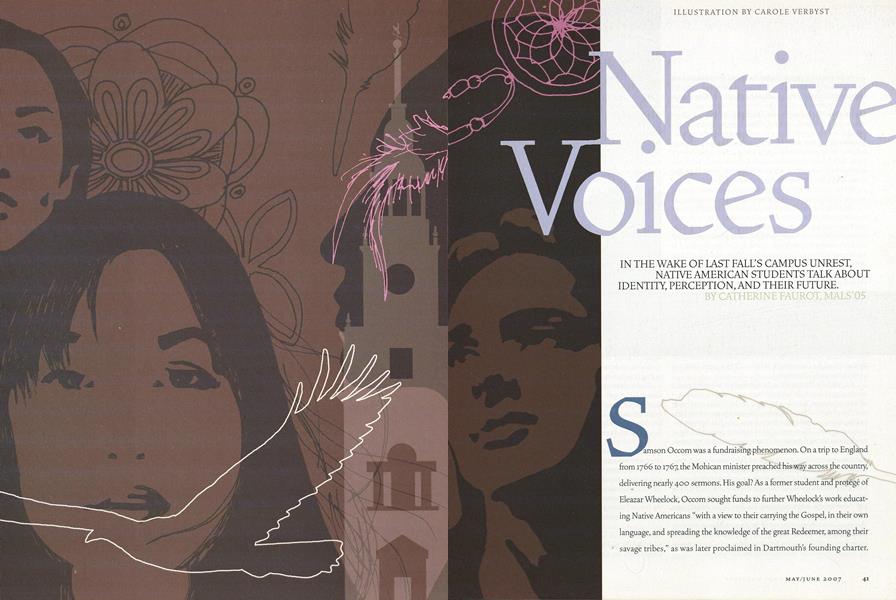

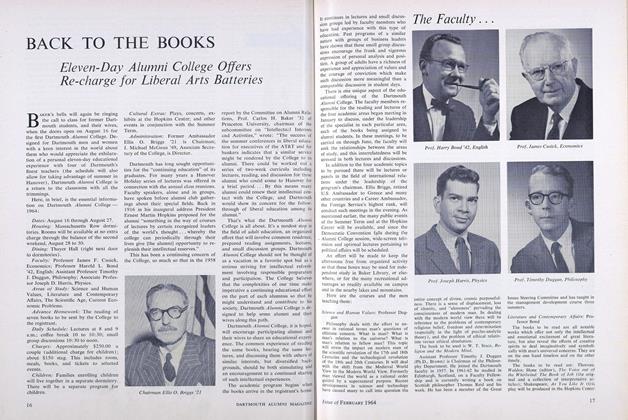

Native Voices

In the wake of last fall’s campus unrest, Native American students talk about identity, perception, and their future.

May/June 2007 CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’05In the wake of last fall’s campus unrest, Native American students talk about identity, perception, and their future.

May/June 2007 CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’05IN THE WAKE OF LAST FALL'S CAMPUS UNREST, NATIVE AMERICAN STUDENTS TALK ABOUT IDENTITY, PERCEPTION, AND THEIR FUTURE.

Samson Occom was a Fundraising phenomenon. On a trip to England from 1766 to 1767, the Mohican minister preached his way across the country, delivering nearly 400 sermons. His goal? As a former student and protege of Eleazar Wheelock, Occom sought funds to further Wheelocks work educating Native Americans "with a view to their carrying the Gospel, in their own language, and spreading the knowledge of the great Redeemer, among their savage tribes," as was later proclaimed in Dartmouth's founding charter.

By the end of his travels Occom had raised more than 12,000 pounds (more than $1.5 million in todays dollars), including sizable donations from both the Earl of Dartmouth and King George 111, for that purpose. But the vision Occom worked so hard to fund did not immediately come to pass. The charter of Wheelock's Dartmouth also mentioned that the College might, without the "least impediment" to "carrying on the great design among the Indians," be enlarged to teach the English. Reportedly because of disappointing results at his Moor's Charity School in Connecticut, where many Native American students died of illnesses or failed to take up missionary work upon graduation, Wheelock changed his focus to teaching English colonists once he arrived in Hanover.

Occom was livid. In its first two centuries Dartmouth enrolled only 19 Native Americans among roughly 40,000 students.

Thanks to Dartmouth President John Kemeny's recommitment in 1970 to educating Native Americans, today there are more of them pursuing degrees at Dartmouth—160, or about 3 percent of the student body—than at any other Ivy. In many ways they are typical undergraduates: passionate about the College, immersed in studies and activities, busy forging friendships. At the same time they are engaged in a struggle to transform education from a means of obliterating Native American culture into the means of preserving and strengthening their rights and identity. "Nowadays," says Heather Yazzie '07, a Navajo from Heartbutte, New Mexico, "it's all about being word warriors." Never has that been clearer than in the wake of events on campus last fall.

BLEEDING GREEN

"DURING MY ENTIRE FRESHMAN YEAR I FELT I COULD NOT have made a better choice of which institution to attend," says Samuel Kohn '09, a computer science and Native American studies major from the Crow tribe in Montana. "I bled green, and I was a real champion of Dartmouth."

Yazzie fell for Dartmouth in the eighth grade, when her aunt, a Stanford graduate, took her on an early tour. In spite of the vast difference between Yazzies upbringing on the Navajo reservation and that of most of her classmates (the year she arrived on campus her family got running water at home), she has felt welcome since her arrival. "There were a lot of students who didn't know much about Native Americans," Yazzie says, "and they were open to asking questions in a really careful way. That was a comfort to me that they were interested, even though we didn't have things in common like rowing crew or going rock climbing."

Although many of the Native American students come from urban environments, Dartmouth has worked hard to acclimate those from the reservation to the Ivy League. "The social and cultural gap between the reservation and life here is so huge," says Marissa Spang '07 of the Northern Cheyenne and Crow tribes in Montana. "I was always at the top of my class back home, but there are all these kids here who went to top schools and whose parents are really well off. The Native American community here serves as my bridge between the reservation life and Dartmouth."

The Colleges Native American program (NAP) acts as an interface between Native Americans and the rest of the Dartmouth community. NAP runs an orientation program for incoming students that takes place in the Native American House, an affinitybased dorm where Native Americans live with students from a variety of backgrounds. "Dartmouth emphasizes that we are distinctive and diverse and that we really contribute to the community," says Spang. "The house gives us a place, visibility within the Dartmouth community. It lets people know that we're still here, we're still alive, we still exist."

NAP also helps with cultural differences. For example, it is culturally inappropriate for many Native Americans to speak to elders without being spoken to first, making it difficult for some students to approach professors. Native American students are also reluctant to make eye contact with elders, even when they are engaged in conversation, so it may appear to faculty that the students are not engaged or able to answer questions directly. NAP offers strategies to deal with such issues, as well as information on how to navigate the academic and social support services available to all students. In addition NAP advises students on applying for internships, how to plan and execute events (such as the Native Summit, an annual networking conference for Native American students across the Ivy League that was originated at Dartmouth in 2004 and hosted in Hanover again last fall) and ways to balance academic and personal goals. NAP also offers support during personal and family emergencies.

The students also have their own campus group, Native Americans at Dartmouth (NAD), an organization many of them describe as essential in creating community among students who otherwise might not connect. (The College also boasts one of the premier Native American studies programs in the country and offers the only B.A. in Native American studies in the Ivy League.)

Like their peers, Native American students are the best and the brightest from their communities. Regardless of their resumes, however—and contrary to myth—there is no free ride for them at Dartmouth. Financial aid is available for all students who qualify, and Native Americans receive no special consideration. (If there are tribal education funds available, NAP helps students apply.) "I have as many loans as anyone else," says Poonam Aspaas '04 of the Navajo Nation in Shiprock New Mexico, who works with NAP in the office of pluralism and leadership.

A UNIQUE MINORITY

CONSIDERING THAT THERE ARE 562 FEDERALLY Recognized tribes, the College has had to work hard to reach out to prospective students and to create an inclusive environment for those who enroll. There is rarely more than one student from any given tribe on campus at a time, with the exception of students from the Navajo Nation, which Yazzie cheerfully describes as "larger than some countries." Due to the U.S. government policy of "termination" adopted in the 1950s and designed to eliminate the treaty rights of North American tribes by relocating their members to urban locations, some Native American students have been separated from their culture.

At the heart of the Native American students' experience at Dartmouth is the unifying fact that all are members of Native nations conquered by the United States. Native Americans accordingly occupy a unique niche among minority groups. Federally recognized tribes are considered "domestic dependent nations." Because of this status, Native nations have independent governments, judicial systems and law enforcement agencies.

In spite of the fact that Native nations have been suppressed by a colonial power, they continue to evolve in the face of ongoing difficulties. They suffer, however, from the burden of invisibility within a dominant American culture that would rather relegate them to the realm of history as a problem of the past. So while Native American students are receiving their education at Dartmouth, they are also offering one to their fellow students on what it means to shift from an American point of view to a perspective of the first Americans.

Time and time again Native American students say that community is what gets them through the experience of being Native students at Dartmouth. "We all have a common history with the United States in terms of colonialism," says Yazzie. "We were the first people on the continent and we all come from a Native background, whether it's on the reservation or in a city. It bonds us together."

For Daniel Becker '09, a Yup'ik Native Alaskan who grew up in urban Anchorage, his double major in Native American studies and creative writing serves to reinforce his Native heritage. His maternal grandfather was a white bush pilot who met and married a local girl while flying from village to village in U.S.Athabascan territory. Becker had never been to his mothers village in southwest Alaska prior to a Dartmouth summer research project trip last year. "According to my Bureau of Indian Affairs card, I'm one-quarter blood quantum [a measure of racial inheritance]. I'm simultaneously learning Native American studies and learning how to be Native," he says. "And to do that I need to be connected to my family."

In 2006 Native American playwright William Yellow Robe staged his Grandchildren of the Buffalo Soldier on campus. Becker says the play profoundly influenced his ideas about mixed-race heritage. "Even though I'm part Irish, it's important to acknowledge both parts of my background," he says, "but it's essential for me to choose where my heart lies so as not to be fragmented. I've always been first and foremost a Native person."

Through such activities as the Native Summit, undergraduates forge connections to a larger Native American community. At the gathering's opening dinner in Brace Commons last November, NAD co-presidents Schuyler Chew '09, a Mohawk and Tuscorara computer science major from Lewiston New York, and Yazzie welcomed the students. Keynote speaker Dr. Michael Yellow Bird pronounced a blessing in his Native language and offered a plate to the ancestors in accordance with tradition. Before the stampede to the spaghetti trays could start, NAP director Michael Hanitchak '73 called for silence. He wanted to talk about community.

"What do we think about when we look at our reasons for coming to Dartmouth?" he asked. "Often we think about getting an education, about getting ahead. But those words—'getting ahead'—imply that someone or something is left behind. Leaving people behind is not what Native people do. Native people are about community and bringing everyone forward together." It is a vision of community Hanitchak wants to extend to all of Dartmouth, a vision he says is shared by his colleagues in the administration but threatened by a small percentage of unaware or hostile Dartmouth students.

For Aaron Sims '09, an Acoma student from New Mexico majoring in computer science, Hanitchak's words clarify conflicting values he has received from his Native heritage and American culture. "I've always been taught to help others. That is what my family taught me and what my community taught me," he says. "In traditional ceremonies first we give thanks for everything—the land, animals, people—before we focus on ourselves. Capitalism has taught me to look out for myself. For me it's come down to the question: 'Do I want to make a buck or do I want to help people?' "

For many Native students their time at Dartmouth is a prelude to tribal service. Yazzie has a double major in environmental studies and Native American studies because, she says, "I grew up around the uranium mines and was always wondering why my people were getting sick." Similarly, Dailan Jake long '07, a Navajo from the Four Corners area of the Southwest, is an environmental activist fighting the construction of a new power plant on the reservation there. It's not necessarily easy to carry such a burden. "It's a white privilege to walk into a classroom, learn about all these issues and then be able to walk out again without having to apply it to your lives," says Spang.

SYMBOLS AND MASCOTS

ALTHOUGH NATIVE AMERICAN STUDENTS ARE EMBRACED on campus by both the administration and an overwhelming majority of students, a small but vocal minority of students greet Native Americans differently. Each fall The Dartmouth Review e-mails the entire incoming class with an offer of free Indian symbol T-shirts. Many students who view such gestures as harmless homage to a discontinued tradition are surprised to find the symbol or other appropriations of Native American history perceived as racist or a painful reminder of genocide.

For Native students, some of whom come from schools with Indian symbols and mascots, the image takes on a different meaning at a school with Dartmouth's history than it does at a school where the overwhelming majority of students are Native American. Rather than images of cultural pride, Indian symbols become images of cultural domination. "The problem with the Dartmouth Indian," says Sims, "is not that the particulars of the image need changing. It's that the image itself is a symbol of 500 years of oppression. There's a sense of entitlement and ownership in the idea that one group can simplify and minimize a whole people down to a symbol."

In fact, the American Psychological Association, based on a growing body of evidence on the negative effects of racial stereotyping on Native American youth, has called for an end to the use of Indian symbols and mascots by schools, sports teams and organizations. A related irony is that despite the warlike character of many Indian mascots, Native Americans are more than twice as likely to experience violence at the hands of whites than any other ethnic group in America, according to federal crime statistics.

The annual reappearance of the Indian symbol was the first in a series of events in the fall of 2006 that made many Native American students question how welcome they really are on campus. On Columbus Day 2 00 6 Native students met at midnight on the Green, as they have for many years, in a sacred drumming ceremony to honor their dead ancestors. As Colin Calloway, longtime chairman of the Native American studies department, pointed out in an October 9 interview with The Dartmouth,"[ Columbus Day] is not just a success story, not just a story of nation building and triumph. There's always a flip side...always someone on the receiving end."

That night the drumming circle was violated—allegedly by drunken fraternity pledges. "We were recognizing over 500 years of genocide that resulted in millions of indigenous casualties—and we were interrupted," says Timothy Argetsinger '09, an Inupiaq student from Anchorage, Alaska. "This would never have happened at a Holocaust memorial or a Martin Luther King Jr. vigil." Although the event was widely discussed among Native American students, they chose not to make any public statements. But the tension surrounding the Indian symbol intensified during Homecoming Weekend with the unsanctioned sale of T-shirts showing a Holy Cross Crusader on his knees performing a sex act on an Indian.

"To see an image like that," says Aspaas of NAP, "is so degrading and hurtful that it turns your stomach. And if people are having a good time, laughing about it, you can't understand why hurting someone is part of having a good time." Aspaas counsels students who are upset by culturally insensitive incidents on campus, often working 11-hour days even before the incidents of the fall to respond to requests for help. Although she misses the wide-open spaces and colors of her hometown in Shiprock, New Mexico, Aspaas says she came back to help Native students know they belong at Dartmouth.

"I've felt relatively comfortable on campus, except for last fall," says Teresa Renee Smith 'OB, a Shawnee government and psychology major from El Dorado, Kansas. "But my family taught me that the stress and anguish I feel at Dartmouth will only make me stronger in the end and that people are the same no matter what region of the country I am in. There will always be someone who hates me, not because of who I am but because of what I am."

Tensions also rose last fall when Native American alumni complained about a photo including an Indian head cane in the 2007 alumni calendar published by the development office. Although they understood the image represents a symbolic connection between past and present, both Native American alumni and students saw it as tacit administrative approval of the image.

These simmering tensions moved to the front burner when Dartmouth men's and women's crew teams held a costume party with a cowboys-and-Indians theme the first weekend in November. On one side of the divide were non-Native students who were revisiting childhood fun; on the other side Native American students saw icons of genocide, colonialism and appropriation. Although the crew team captains immediately and publicly apologized, many Native American students saw another example of cultural Insensitivity that made them question their place in the larger Dartmouth community. On a broader scale, Native American students also understand that what happens on campus is a microcosm of what is happening in the country as a whole. The issues, says Sims, "are bigger than just the Indian symbol."

Ironically, the long-planned centerpiece of the November Native Summit was a presentation on the Dartmouth Indian symbol, and many members of the crew team attended as a conciliatory gesture. Native Americans on campus, including students, alumni and administrators, carefully framed the event as an occasion for reconciliation.

In her role as a Rauner Library manuscripts specialist, Mauli Watkins 'O6 of the Choctaw Nation from Oklahoma City set the tone by asking for a discourse respectful to all points of view, including those of the athletes present. This culminated in an impromptu speech by Dr. Lori Alvord '79- a Navajo surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center and associate dean at the Medical School, who expressed her understanding of the alumni attachment to the Indian symbol. "It's embedded in their love of the College," she said, "and I get that. I understand how much I love this College."

After the presentation students helped themselves to a Chinese food banquet in the basement of Filene Auditorium and adjourned to small discussion groups. In one room crew team members gathered with Native Americans, along with a smattering of other interested students. Peterson Brossy '07, a Navajo from Honolulu, Hawaii, who rowed his freshman year, came to the meeting to help forge connections between Native Americans and crew team members. "I know the leadership of that group," he says, "and I came because I thought I could temper things a bit, maybe make a bridge. Crew is the whitest sport this side of croquet. As the only non-white person I felt all kinds of pressure to perform well and represent Indians in a positive light. There were some stresses, but in the end my teammates let me know I was an integral part of the team."

Still, the issues surrounding the Indian symbol tap into deep questions of identity, power and control, and for a while emotions ran high on both sides of the room. At a certain point an Oglala Sioux graduate fellow, who wishes to remain anonymous, addressed the rising hostility.

"I'll tell you a story," he said quietly, as the students in the room leaned forward. He described a playdate when he was 9 years old with a white friend who wanted to spend the night at his houseuntil the moment his father was due to arrive home. "My friend started crying, and I was doing the things a little kid does, asking if he was okay. And he says, 'ls your dad going to scalp me?' "

The story helped to put a personal face on the academic explanations of the damaging effects of Indian symbols. The Native American students had come looking for a face-to-face apology, and in the end they got one. "I'm sorry," said heavyweight crew cocaption Abraham clayman '07. It was clear he meant it. In that one room, at least, a slender bridge of reconciliation had been forged. But the double burden facing the Native American students remained: having to experience incidents, whether rooted in racism or thoughtless behavior, then having to explain why they hurt.

FINDING A VOICE

AFTER MONTHS OF GROWING FRUSTRATION, ON NOVEMBER 20 the Native American Council (NAC), a group of Dartmouth faculty, staff and students, purchased a two-page ad in The Dartmouth describing the incidents that bothered Native American students last fall. That same day President James Wright sent a campuswide e-mail apologizing for the incidents and asking students to make the College more welcoming to Native American students. "They are members of this community...they are your classmates and your friends," wrote Wright. "And they deserve more and better than to be abstracted as symbols and playthings. On November 21 athletic director Josie Harper made an apology of her own for having invited the Fighting Sioux of the University of North Dakota to compete in a December hockey tournament scheduled years in advance. (An NCAA ban on the. UND nickname and mascot is in litigation.)

On November 28 The Dartmouth Review, reacting to the NAC statement, President Wright's letter and Harpers apology, published an incendiary issue sporting a cover illustration of an Indian brandishing a scalp with the headline "The Natives Are Getting Restless!" The tone of the lead article, titled "NADs on the Warpath," might be summed up as trivializing. "It is as if a large, dust-covered quadrennial alarm clock in the Native American House suddenly sprung to life and alerted the Native Americans at Dartmouth (NADs): It's time to start being angry again," wrote editor Daniel Linsalata '07. Other articles mocked the Native American students as overly sensitive and humorless.

The following day an estimated 500 students with representation from across the spectrum of student cultural groups, administrators and faculty members gathered for a "Solidarity Against Hatred" rally on the Green. President Wright spoke. In the following weeks Review editors apologized for the cover, admitting "boorishness," but defended the editorial content of the issue. Later Review president Kevin Hudak '07 resigned.

Nothing was done by the administration until the NAC publication in The Dartmouth."

"I feel I'm a joke here with how people treat Native people," says Long. I dont feel comfortable saying I'm a Dartmouth student because this stuff is going on.

Faculty members to whom Native students have turned empathize deeply. "The events of the past year have left many students feeling frustrated and distrustful, says Calloway. "Although Dartmouth recommitted itself to Native American education in 1970, it's time to reaffirm that recommitment by trying to make sure this is an environment where Native students feel welcome and eager to learn, not Harrassed and ready to leave."

Sims has considered how the perspective represented by The Dartmouth Review translates to the national arena: "It's scary to realize that the kids here are going to be the people who are in positions of power one day, knowing that they have these traditions of thought embedded in them. But then I remember that I'm on the same playing field. The same level of influence they have from being here, I have too."

Argetsinger Argetsinger says the events on campus last fall have strengthened his ties to Dartmouth. "The rally showed me that a large proportion—maybe a majority of Dartmouth students—no matter what their skin color, are progressive-minded and concerned about the well-being of others, he says. "But I must point out that I never really felt a lack of support on campus. I never felt victimized throughout the course of these incidents. The only thing that has been offended has been my intelligence. I Know who I am and where I come from and that is enough."

Argetsinger's s confident attitude would likely make Samson Occom proud. In the past 35 years approximately 600 Native American students from more than 200 tribes have graduated from the College. Many have distinguished themselves in the same variety of fields inhabited by their classmates, often working for their tribes and inspiring others to come to Dartmouth, where Occom's hopes for the original Dartmouth are at last bearing fruit in New Hampshire's granite soil.

"Even though I'm part Irish, its important to acknowledge both parts of my background," says Daniel Becker 09, a Yup'ik Native Alaskan. "I've always been first and foremost a Native person."

"I feel I'm a joke here with how people treat Native people," says Dailan Jake Long by, a Navajo from the Southwest. "I don't feel comfortable saying I'm a Dartmouth student because this stuff is going on."

CATHERINE FAUROT is a regular contributorto DAM. Her last story was "Not Your Mother'sBible" in November/December 2006.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHostile Takeover

May | June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05 -

Feature

FeatureA Different Kind of Homeland Security

May | June 2007 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2007 By Joe Novak '52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May | June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2007 By BONNIE BARBER