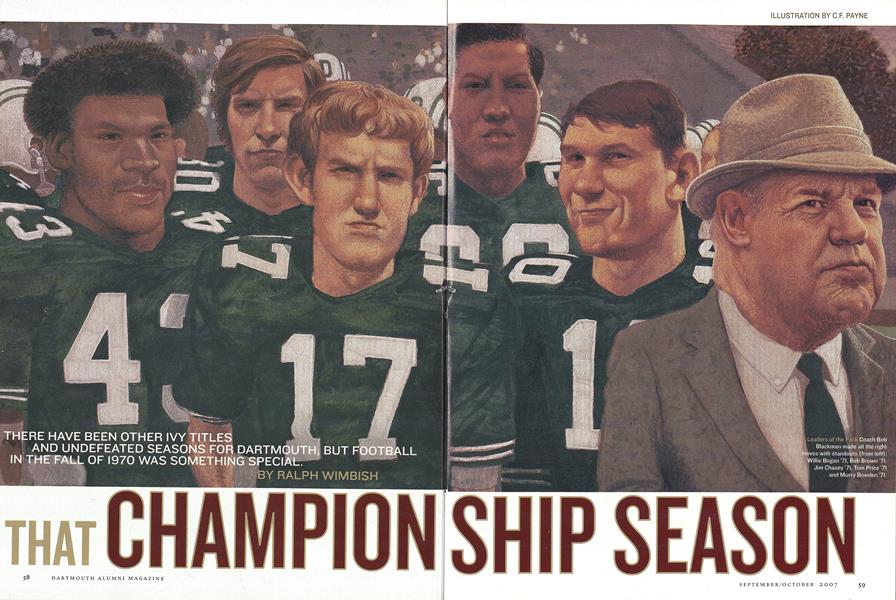

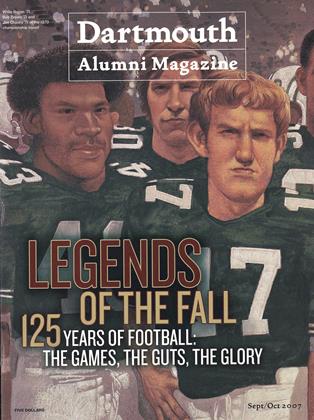

That Championship Season

There have been other Ivy titles and undefeated seasons for Dartmouth, but football in the fall of 1970 was something special.

Sept/Oct 2007 RALPH WIMBISHThere have been other Ivy titles and undefeated seasons for Dartmouth, but football in the fall of 1970 was something special.

Sept/Oct 2007 RALPH WIMBISHTHERE HAVE BEEN OTHER IVY TITLES AND UNDEFEATED SEASONS FOR DARTMOUTH, BUT FOOTBALL IN THE FALL OF 1970 WAS SOMETHING SPECIAL.

1970

while Hair was Humin' on Broadway and Streisand was singing her heart out, Bob Blackman was busy orchestrating the greatest football symphony ever played at Dartmouth College.

That was the year the legendary maestro saw his Dartmouth team perform a perfect 9-0 season that included the second of five straight Ivy League titles. The 1970 team was Mr. Blackmans opus.

Blackman really had no ear for music, but, boy, did he love the sound of football, especially the crescendo of cheers that accompanied every one of the 104 victories during his 16-year reign as Dartmouth's head coach.

His team brought home the Lambert Trophy that year as the best team in the East—over Penn State, mind you—and was ranked as the 14th best team in the nation in the two wire-service polls, ahead of perennial powers Southern California (USC) and Oklahoma. Blackman's team never trailed in any game that season and outscored opponents 311-42. So dominant was the defense that Dartmouth posted six shutouts, including four straight to end the season.

It's not surprising some experts say Blackman's team, led by 26 talented seniors from the class of 1971, was the greatest team in Dartmouth's fabled football history. Seventeen players on that team received All-Ivy League recognition and five were named All-East.

"They were the last great Ivy League team. They could have played with anyone in the country," says Ed Marinaro, the storied Cornell running back turned actor who sang the "Hill Street Blues" in 1970 when he and the Big Red faced Blackman's Green Machine.

To each of his players Blackman was like a Nat King Cole song- unforgettable in everyway. "Coach Blackman made it possible for us to execute at the highest level possible," recalls Murry Bowden '71, the co-captain and College Football Hall of Famer. "We had lots of characters on our team but everybody loved each other."

Blackman, labeled "an Ivy League Lombardi" by SportsIllustrated, was a barrel-chested mound of testosterone with the mind of a genius. His distinctive, authoritative voice sometimes was downright frightening, especially when amplified by his trusty bullhorn. In a sweatshirt at practice he looked like Bill Belichick; at games he resembled Hank Stram, always dapper in a coat and tie with a fedora on top.

"He was a gentleman, and that's what I remember about him most," says co-captain Bob Peters '71, an All-Ivy defensive tackle who describes himself as one of Blackman's "unruly" players. "I didn't appreciate his good example at the time. But after graduating from Dartmouth I came to realize what a rare human being he was. On one hand he was diligent, persistent and tough. But on the other hand he attempted to show appreciation for each player."

"Bullet Bob" prowled the sidelines with a limp, the result of a battle with polio in 1937 when he was a freshman football player at USC. He was given little chance to walk again, but one year later he was back on the football field. After the war he became a head coach: first at the San Diego Naval Academy, then Pasadena City College and eventually Denver University.

In 1955, after "Tuss" McLaughry had been fired after a fifth straight losing season, Dartmouth turned to legendary NFL coach Paul Brown for help. Brown, whose son Mike '57 was a quarterback at Dartmouth, formed a committee that recommended Blackman for the job.

Few coaches ever had Blackmans passion for the game. At practices there always was a premium on precision. Every player received a mimeographed sheet with timetables and charts, each one detailing exactly what he was to do when on the field. And each of Blackmans drills was timed to the minute.

"Sometimes he was a pain in the ass," says Bob Cordy '71, a former offensive guard who turned into a Massachusetts Supreme Court judge. "I liked him, but he wasn't a buddy-buddy guy. He meant it when he said he wanted 110 percent. He'd say, 'This is the game and how it is to be played. If you want to win, this is how it's supposed to be done.'"

Blackman was among the first college coaches to use computers to track the tendencies of opponents. And when it came to of-fensive play-calling, he was the Lex Luthor of his day, notorious for conniving, diabolical offensive schemes that featured reverses and lateral passes. To avoid penalties Blackman often went to the referees before the game to warn them about any trick plays he might use that day.

"He was obsessed, an organized genius," says Dan Radakovich '71, an offensive lineman who is now an attorney in Chicago. "He was the most organized person I ever knew. He broke it down so you could know your function, and it all fell into place. If it wasn't perfect, it wasn't good enough. Every aspect of the game—from the way we dressed, lined up, played, everything—had a purpose."

Blackman made it all work by establishing a solid national recruiting network that included coaches, alumni, friends, anyone who could convince some of the country's top high school athletes-some with football scholarship offers from other schools—to come to Hanover.

"At Dartmouth," Blackman would say, sans the bullhorn, "you'll get a great education and have some fun playing football."

"I don't think anyone chose Dartmouth just because it had a great football team," says Peters. "You also chose Dartmouth becase it was a great school."

Blackman, who had undefeated teams in 1962 and 1965, realized there was something special about those freshmen who arrived in the fall of 1967. More than 100 students—that's about one out of every five in the class—went out for the freshman team back in the days when first-year students were excluded from varsity play. Socially diverse, they came to New Hampshire from places such as Snyder,Texas; Glendale, Arizona; and Bozeman, Montana.They came when the rimes were a-changin' all across America. With the Vietnam War and the civil-rights battle ongoing, there was turmoil everywhere except on Blackmans football field.

"There was so much going on somehow or other, but all we could think about was the next play at practice," says Tom Price '71, a defensive end and one of 10 blacks on the roster in 1970, now a cardiologist in New Rochelle, New York. "Football allowed us to get away from the times. There were radicals on campus, but no one said football players had to take a stand. We were not politicians."

Maybe the smartest move Blackman ever made at Dartmouth occurred early in the 1968 season, when he played many of his sophomores throughout a 4-5 season, giving them the added experience they would later need to put Dartmouth back atop the Ivy League. Blackman also brought in an assistant coach named Charlie Harding, who stressed physical fitness.

"Everyone hated this guy," says John Short '71, the team's star running back who has stayed in decent shape while running his own business-consulting firm in Scottsdale, Arizona. "But his killer training regimen took our physical conditioning up several notches It made us a better team in the third and fourth quarters."

In 1969 Dartmouth went 8-1 and won a share of the Ivy League title, but the whole season is remembered by the one game the team didn't win—a 35-7 thumping at Princeton.

"I still have nightmares over it," Cordy says. "Blackman panicked. We saw Blackman like wed never seen him before. He made all these complex changes on the offense and on our approach, and it didn't work. That loss made us miserable and we made sure it never happened again." By the following September Blackman's ornery team was determined to go the distance.

"We could be arrogant, we could be nasty, hit Marinaro and tell him not to get up," says Barry Brink '71, a defensive tackle who, along with safety Willie Bogan '71 and Bowden, were known as the Killer B's.

Says Price: "There was nothing like walking into somebody's stadium, knowing there was nothing the other team could do to win. We knew we were the better team on both sides of the ball."

That season Dartmouth's "D" ranked in the national top 10 in seven statistical categories, including first in scoring defense, second in total defense, third in rushing defense and fifth in pass defense. Led by assistant coach Jake Crouthamel '60, the defense was so good, it even had its own theme song—"Green-Eyed Lady," a one-hit wonder on the radio by a rock band called Sugarloaf.

"We'd hear it on the bus ride to the stadium every game," says Bill Skibitsky '71, a defensive tackle back then and now owner of an engineering/construction firm in North Carolina.

"That was our anthem; our good-luck song," says Tim Risley '71, the hard-charging defensive lineman from Harrison, Arkansas, who returned to his home state after Dartmouth and is now an architect in Fort Smith. En route to the Penn game that year the song didn't come on the radio. "We had to stop the bus and call the radio station in Philadelphia," says linebacker Joe Jarrett '71, who is now an orthopedic surgeon in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. "We got it played and we won the game."

Joining Jarrett at linebacker were Wayne Young '72 and Bill Munich '71. The secondary was outstanding with Jack Manning '72, Mike Hannigan '71 and Russ Adams '71. And there was Bogan, who is now assistant general counsel for the McKesson Corp. in San Francisco—a future Rhodes Scholar who topped the team in appearences inside Baker Library.

"Willie was a great player. We trusted each other knowing he was back there," says Brink, now a clinical psychologist in State College, Pennsylvania. "He had no interceptions his senior year because nobody ever threw at him."

And nobody ran at Bowden, No. 10, the co-captain from Texas who played the rover-back position with the vengeance of a rabid Mack truck. At 5-foot-10 and 190 pounds, he was a fearless tackier and the teams inspirational force.

"I loved Murry," says Bogan, the only player from that team to be drafted by an NFL team, the Baltimore Colts. "As a defensive player he played with what was a reckless—actually it was a controlled—abandon. I considered myself a hard tackier, but I was always amazed by what Murry could do with his body. He was like a missile."

Marinaro puts it bluntly: "People ask me who hit me the hardest, and I tell them Murry Bowden, and that includes the NFL."

Bowden, renowned for "accelerating through impact," played every game as though he were on the verge of a season-ending injury, Prior to the 1970 season he had surgery to repair shoulder and knee injuries, and he always suited up with a specially designed brace to keep a shoulder in place.

"Murry invariably made aplay early in the game that ignited our defense," recalls Young, who later co-captained the 1971 team. "He would hit someone so hard that he would come back to the huddle with his facemask crooked and a grin on his face."

Dartmouth's defense was perfectly complemented by its offense. "It was a super combo," says Bowden, who for three decades has aggressively run his own real estate development firm, Hanover Cos., in Houston, Texas. "Our offense knew our defense wasn't going to let anyone score."

Peters, the former hell-raiser who nowadays is president of a New York group called Morality in Media, led an offensive line that included tackle Joe Leslie '72, tight end Darrel Gavle '71, center Mark Stevenson '71 and Cordy and Jim Wallace '71 at the guards. In the backfield there was Brendan O'Neill '72, Stuart Simms '72 and Short, the sparkplug who rushed for a team-record 787 yards, caught 25 passes and scored 15 touchdowns to win the Ivy League scoring title.

Says Adams: "We always said the hardest team we ever had to play was our own offense in practice."

The quarterback was Jim Chasey '71, a California beach bum who shared Ivy League Player of the Year honors with Marinaro and later went on to play in the Canadian Football League with the Montreal Alouettes. While Chasey has spent much of the past two years in New Zealand exploring business opportunities, his former teammates continue to marvel at his guile, skill and tenacity.

"I was one of 17 quarterbacks at freshman tryouts," Short recalls. "Chasey was clearly the coach's favorite, good judgment on his part. Jim was a very reliable person, an absolutely fluid athlete, deceptively fast and he threw the ball well."

"I was always worried about him. He was so laid back; nothing ever bothered him," says Risley. "I guess that's what made him such a good quarterback."

Nicknamed "The Snake," Chasey missed the first game with an ankle injury incurred in a 46-6 scrimmage win over Vermont. Still, with Steve Stetson '73 and Bill Pollock '72 filling in at quarterback, Dartmouth overcame a sluggish start to beat Massachusetts 27-0 in the season opener at Memorial Stadium, thanks in part to a blocked punt by junior Jim Macko '72 and a 73-yard punt return by junior Tim Copper '72.

Chasey came back the following week and led the Green to a 50-14 victory at Holy Cross. Unlike the previous year, when a few of the Holy Cross players came down with hepatitis, nobody had to be vaccinated this time. ("When they stuck Barry Brink with that big needle, he cried like a baby" Risley recalls of the 1969 incident.)

After Holy Cross came Princeton. It was time for revenge, and this time it was no contest. On Dartmouth Weekend the largest crowd (21,416) in Memorial Fields history saw the Green mount a 24-0 halftime lead en route to a 38-0 victory.

"They didn't have a chance," says Radakovich. "We destroyed them. They didn't realize how good we were."

After an easy win over Brown (42-14), Blackman notched his 100 th win at Dartmouth with a 37-14 victory before a crowd of 35,000 at Harvard. Short had a big day, rushing for 106 yards and two touch-downs and throwing a 49-yard option pass to Bob Brown '71.

"No doubt this is a great Dartmouth team," Crimson coach John Yovicsin said that day. "They strangle you on defense and won't let you breathe on offense."

Halloween arrived one week later and with it came the big show-down at Yale. A sun-soaked crowd of 60,820, plus a regional television audience, saw a slugfest between two (gasp!) nationally ranked Ivy League teams. Dartmouth prevailed in what one sports-writer said was "the most lopsided 10-0 game in the history of Ivy League football."

The Big Green rolled up 480 yards of offense, but was throttled by a slew of penalties and inopportune fumbles and interceptions. O'Neill ran three yards for the games only touchdown in the second quarter. Dartmouth might have scored more points if placekicker Wayne Pirmann '72 hadn't played in a soccer game in Hanover that morning.

Here's how Sports Illustrated reported it: "It fell to an eager Dartmouth grad, Class of '33, to volunteer to fly Pirmann to New Haven. When at last Pirmann arrived at the stadium, no doubt sped there from the airport ...in a roadster, he trotted onto the field near the end of the halftime show to try a few warm-up kicks and was promptly pushed aside by the band. Later, however, Pirmann proved himself to have been worth the trouble by kicking a 30-yard field goal the only time he was allowed to swing his leg."

"We went into the Yale game taking it one game at a time, being afraid all week we might lose," says Brink, Sport Illustrated's defensive player of the week. "They were the only team that had a chance to beat us. It was a healthy fear, if you know what I mean. Once we got that game, we knew we could go undefeated."

In the home finale against Columbia Chasey raced 75 yards for a touchdown and Copper returned a punt 64 yards in a 55-0 romp. Then it was on to Cornell. That was the week where Blackman goofed and booked the team into a hotel in Saratoga Springs, several hours from Ithaca. When Blackman discovered his mistake and found out the girls at Saratogas Skidmore College had planned a pep rally, he set a curfew for 9 p.m.

"I always had to negotiate with Blackman," Bowden says. "I told him wed shut it down by 10. He just shook his head and said, 'We'd better win.' And we did."

The score was 24-zip. On a muddy field, Short rambled for 192 yards while Marinaro, the nations leading rusher who was averaging 166 yards a game, managed only 60 yards on 21 carries. Jarrett had a memorable game, intercepting two passes intended for Marinaro, and shared the game ball with Risley.

"They really had a good defense," Marinaro recalls. "They were our nemesis. We were grooming ourselves for our '71 run, but they ran over us."

Then 8-0, there was just one game to go. Because the Ivy League didn't allow its teams to accept bowl invitations, the game at Penn was the last hurrah.

Ironically for Price, it fell on the same day, November 14, that a plane crash took the lives of almost the entire Marshall University football team. Had he not chosen Dartmouth over Marshall, which had recruited him, Price probably would have been on that plane.

Playing before a spirited crowd of 42,329 and on artificial turf for the first time, Dartmouth dominated the Quakers as Short ran for 154 yards and three touchdowns, Chasey completed 15 of 19 passes for 164 yards and Bowden—named to the Ail-American team the day before—intercepted three passes. But the big news was how close Penn, led by quarterback Pancho Micir, came to ending Dartmouth's shutout streak.

"Penn got down to the 7-yard line in the second quarter," Skibitssky recalls. 'And we knocked them back. It's like we said, 'Okay, that's enough.'"

On three straight plays Dartmouth's defense responded with big plays. After Price and Skibitsky sacked Micir on third down at the 24, Penn tried a 42-yard field goal that sailed wide right. Penn never came close again—and Dartmouth had its fourth straight shutout. Before it was over, though, the boys had a little fun. In the final minutes, after it became 28-0, the guys on defense were ready to unleash what they called "the triple thunderbolt." After the kickoff, they would run onto the field—and switch positions. Bowden and Bogan would play on the line; Skibitsky was to play safety—almost daring Perm to break the shutout streak.

For three years Moore had practiced onsides kicks but never had a chance to do one in a game. "In the huddle I said, 'Let's give Bobby a chance,'" says Adams, who usually did the kickoffs.

It was now or never, so Moore got the sign from Adams and squibbed the kick. Risley recovered the ball and Blackman went ballistic. "He told me to go apologize to [the Penn team] after the game," Moore recalls.

All was quickly forgotten once the game ended as Blackman was carried to midfield on the shoulders of Fred Radke '73 and Giff Foley '69. Minutes later it was all aboard for the bus ride to the season-ending dinner at the New York Athletic Club. It was a memorable, two-hour trip. Girlfriends were allowed to come along, and the coaches even permitted a beer stop.

"It was a great celebration the whole night," Moore says. "It got pretty crazy, as wild as you can imagine."

The perfect season was over, and soon after so were Blackman's days at Dartmouth. After he was named Walter Camp National Coach of the Year, he packed his bags for Illinois and rode into the sunset of the Big Ten. Before he went he turned down a challenge from Penn State coach Joe Paterno, whose team had finished with a 7-3 record.

"If we were allowed to play in such a game," said Blackman, "we would prefer to play a team that had a better season record than Penn State."

That was the Maestro. This was his opus.

We Were the Champions The 1970 team was distinguished by 17 All-Ivy and five All-East players.

"COACH BLACKMAN MADE IT POSSIBLE FOR US TO EXECUTE AT THE HIGHEST LEVELPOSSIBLE," RECALLS MURRY BOWDEN '71.THE CO-CAPTAIN AND COACH, LEFT, WITH THE LAMBERT TROPHY

RALPH WIMBISH is assistant sports editor at the New York Post Helives in Mount Vernon, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

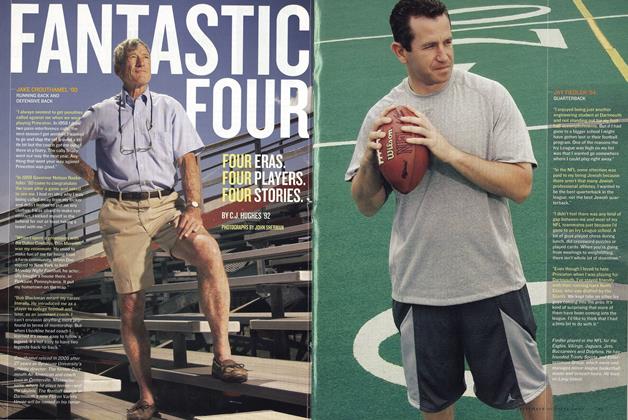

FeatureFantastic Four

September | October 2007 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

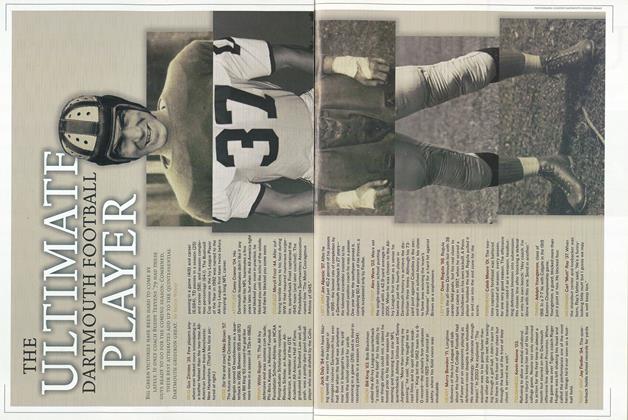

FeatureThe Ultimate Dartmouth Football Player

September | October 2007 By Bruce Wood -

Feature

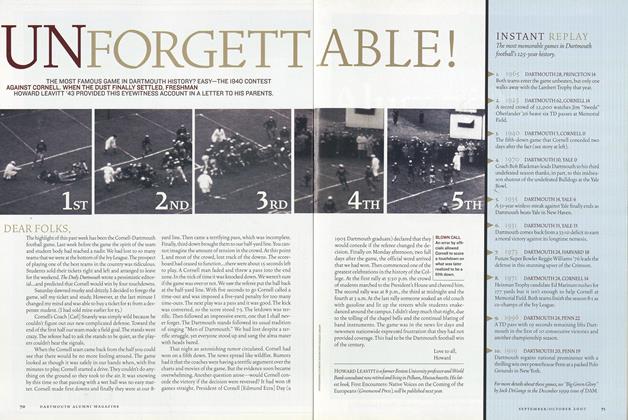

FeatureUnforgettable!

September | October 2007 By HOWARD LEAVITT ’43 -

SPORTS

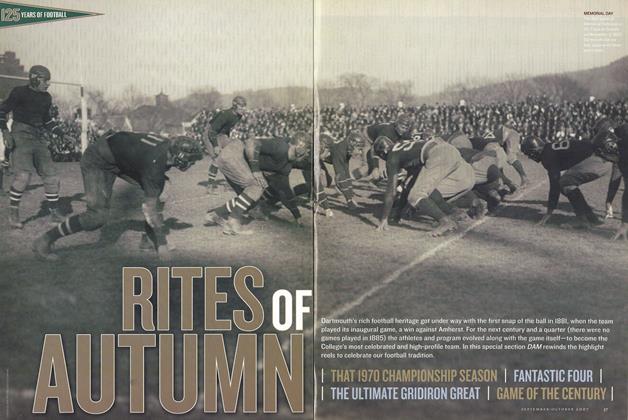

SPORTSRITES OF AUTUMN

September | October 2007 By Courtesy Dartmouth College Library -

Feature

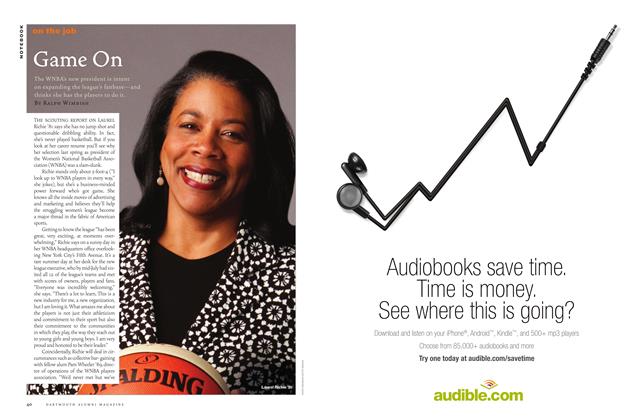

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2007 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2007 By Kristine Keheley '86

RALPH WIMBISH

Sports

-

Sports

SportsARRIVAL OF COACH DENT FORECASTS BETTER SOCCER TEAM

November, 1924 -

Sports

SportsDartmouth 45, Williams 36

March, 1926 -

Sports

SportsDartmouth's in Town Again!

November 1934 -

Sports

SportsWinter Schedules

December 1950 -

Sports

SportsGREEN MANPOWER TELLS

February 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Sports

SportsDARTMOUTH 21, CORNELL 13

December 1947 By Francis E. Merrill '26