The Whistleblower

Every fall, business law professor Darryll Lewis ’75 leaves his classroom to teach NFL players a few lessons—on the field.

Nov/Dec 2008 Ralph WimbishEvery fall, business law professor Darryll Lewis ’75 leaves his classroom to teach NFL players a few lessons—on the field.

Nov/Dec 2008 Ralph WimbishEvery fall, business law professor Darryll Lewis '75 leaves his classroom to teach NFL players a few lessons—on the field.

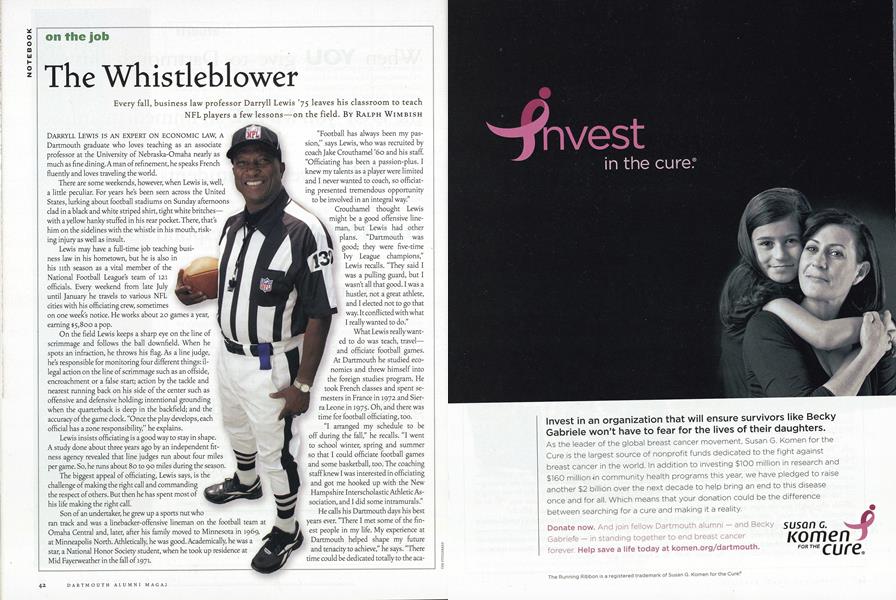

DARRYLL LEWIS IS AN EXPERT ON ECONOMIC LAW, A Dartmouth graduate who loves teaching as an associate professor at the University of Nebraska-Omaha nearly as much as fine dining. A man of refinement, he speaks French fluently and loves traveling the world. 4 111

There are some weekends, however, when Lewis is, well, a little peculiar. For years he's been seen across the United States, lurking about football stadiums on Sunday afternoons clad in a black and white striped shirt, tight white britches with a yellow hanky stuffed in his rear pocket. There, that's him on the sidelines with the whistle in his mouth, risking injury as well as insult.

Lewis may have a full-time job teaching business law in his hometown, but he is also in his nth season as a vital member of the National Football League's team of 121 officials. Every weekend from late July until January he travels to various NFL cities with his officiating crew, sometimes on one week's notice. He works about 20 games a year, earning $5,800 a pop.

On the field Lewis keeps a sharp eye on the line of scrimmage and follows the ball downfield. When he spots an infraction, he throws his flag. As a line judge, he's responsible for monitoring four different things: illegal action on the line of scrimmage such as an offside, encroachment or a false start; action by the tackle and nearest running back on his side of the center such as offensive and defensive holding; intentional grounding when the quarterback is deep in the backfield; and the accuracy of the game clock. "Once the play develops, each official has a zone responsibility," he explains.

Lewis insists officiating is a good way to stay in shape. A study done about three years ago by an independent fitness agency revealed that line judges run about four miles per game. So, he runs about 80 to 90 miles during the season.

The biggest appeal of officiating, Lewis says, is the challenge of making the right call and commanding the respect of others. But then he has spent most of his life making the right call.

Son of an undertaker, he grew up a sports nut who ran track and was a linebacker-offensive lineman on the football team at Omaha Central and, later, after his family moved to Minnesota in 1969, at Minneapolis North. Athletically, he was good. Academically, he was a ' star, a National Honor Society student, when he took up residence at Mid Fayerweather in the fall of 1971.

"Football has always been my passion," says Lewis, who was recruited by coach Jake Crouthamel '60 and his staff. "Officiating has been a passion-plus. I knew my talents as a player were limited and I never wanted to coach, so officiating presented tremendous opportunity to be involved in an integral way."

Crouthamel thought Lewis might be a good offensive line- man, but Lewis had other plans. "Dartmouth was good; they were five-time Ivy League champions," Lewis recalls. "They said I was a pulling guard, but I wasn't all that good. I was a hustler, not a great athlete, and I elected not to go that way. It conflicted with what I really wanted to do."

"I arranged my schedule to be off during the fall," he recalls. "I went to school winter, spring and summer so that I could officiate football games and some basketball, too. The coaching staff knew I was interested in officiating and got me hooked up with the New Hampshire Interscholastic Athletic Association, and I did some intramurals."

He calls his Dartmouth days his best years ever. "There I met some of the finest people in my life. My experience at Dartmouth helped shape my future and tenacity to achieve," he says. "There time could be dedicated totally to the academic experience with so few distractions and so many great people whom I would end up calling friends for life."

His officiating career actually started even earlier. As a teenager Lewis blew his first whistle doing peewee games for the North Omaha Boys Club. After graduating from Dartmouth he went back to Omaha to attend law school at Creighton University. When he wasn't studying torts or contract law he refereed high school games.

By 1980 he was doing college games as an official in the Big 8 Conference, nowadays known as the Big 12.

"I tried working all the positions, but I fell into being a line judge," Lewis says. "I was never a fast person, never fast enough to be a deep official. Having played linebacker and guard, I was well suited to be a line judge."

After Creighton, Lewis spent the next eight years working for an Omaha- based energy company called Inter North Inc. Then he made another good call by getting out of there before it became known as Earon. By that time he had established his own private law practice.

By 1986 Lewis also was teaching at Nebraska-Omaha and sent his resume to the NFL, which began to monitor his work. Lewis excelled as a college ref. Between 1993 and 1996 he was chosen to work the Cotton Bowl, the Rose Bowl, the Peach Bowl and the Alamo Bowl. Finally, after the 1996 season, the NFL offered him a job working games for NFL Europe, the now defunct spring developmental league that began in 1991 as the World League of American Football.

"It was a great experience," Lewis recalls. "We were totally immersed in NFL rules and mechanics. The players were somewhat quicker than what I had been accustomed to [in college football] but somewhat slower than in the NFL.

"We were put on crews with NFL officials who taught you the ropes and application of the rules," says Lewis. I recall calling an unsportsmanlike conduct [penally] on a player who had openly belittled me. The penalty cost his team the game. The veteran officials instrutted that these types of fouls should be avoided because they were difficult to prove. The league supported me, however, because the player had run 15 yards to show me up."

The NFL brought Lewis home for the 1998 season. On December 20 that year in Pittsburgh, Lewis was bulldozed on the sidelines by a linebacker he still can't identify. Despite a serious knee injury that would later require reconstructive surgery, he finished the game—and the rest of the season. Lewis was back on the field the following week, on December 27, for one of his most memorable moments—marking the spot on the play in which Denver Broncos running back Terrell Davis broke the 2,000-yard barrier. At the time Davis' total was the third highest rushing total in NFL history.

"I remember the Terrell Davis moment, but I don't specifically remember handing him the ball," Lewis says.

Lewis had the surgery during that off-season but remained in the game. In 1999, while he underwent extensive rehabilitation on his knee, the NFL reintroduced its replay rule and moved Lewis up to the press box to become one of the leagues first replay officials.

"Being a replay official was a great learning experience," Lewis says. "At that time very few officials had served on the field as well as in the booth. Now, with few exceptions, most of the NFL replay officials are retired NFL officials. So, at the time, I brought some actual NFL officiating knowledge to the booth.

"This was the first year for the digital replay system; before, the system was based on video. It has continued to evolve. I believe that the NFL has a work able system with the actual power to reverse or affirm calls remaining within the sole discretion of the referee, unlike the NCAA, which gives that power to the replay official. The fact that the vast majority of NFL teams voted to make the replay system permanent is a tribute to its success and acceptance."

By 2003 Lewis was back on the field, where he has been focusing on reaching the Super Bowl. To achieve this goal Lewis must compete against fellow official. Every week all are analyzed and graded by as many as three different NFL evaluators.

"We all make mistakes," Lewis admits. "When you make an error, you're downgraded. It's very competitive. The NFL has [supervisors] who call you and tell you what you've done wrong or they'll tell you how to correct your deficiencies. It's the system the league has. It's all a matter of decimal points."

Lewis won't say if he has ever missed a call. "I have never blown a call that affected the outcome of a game," he says. "However, I have made some correct ones during the waning moments of a competitive contest."

Last season Lewis was chosen to work the Pro Bowl, the NFL's all-star game, in Hawaii. Between the 2000 and 2006 seasons he's worked a number of divisional and wild-card games, but he's still waiting for that elusive Super Bowl call.

"That's the ultimate achievement, my dream," Lewis says. "It's the pinnacle. One cannot go any higher. It's the same for the officials as it is for every player in the NFL. That's my goal; that's what I'm going to do."

Gary Love '76, one of Lewis' best friends from Dartmouth, has no doubts Lewis will make it to his promised land.

"Darryll has executed his life plan better than anybody I know," says Love, now an investment banker in San Francisco. "In college he told me he would go to law school and become a lawyer. He did that. He said he'd become a college professor. He did that. He said he wanted to be a Big 8 referee. He did that. He said he'd become an NFL referee. He did that.

"Here was a black man from Omaha, Nebraska—that in itself was amazing who knew exactly what he was going to do with his life," Love says. "To do all that was pretty darn difficult."

Not if your name is Darryll Lewis.

RALPH WIMBISH, an assistant sports editorfor The New York Post; is a regular contributorto DAM.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

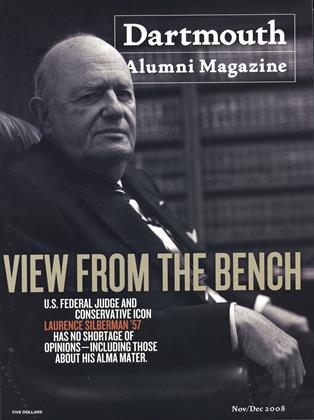

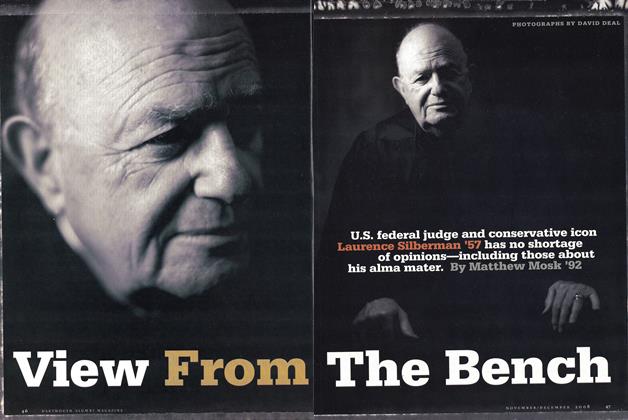

COVER STORY

COVER STORYView From the Bench

November | December 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

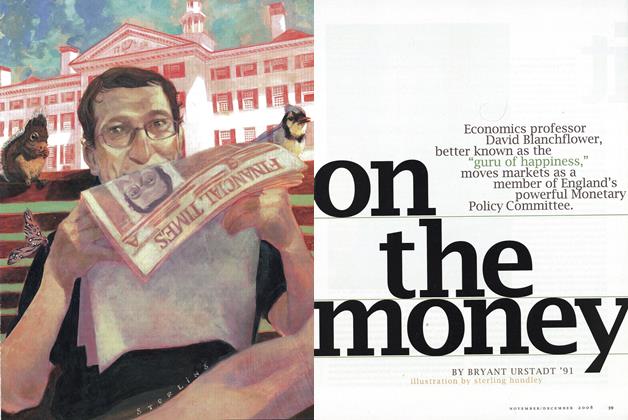

FeatureOn the Money

November | December 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

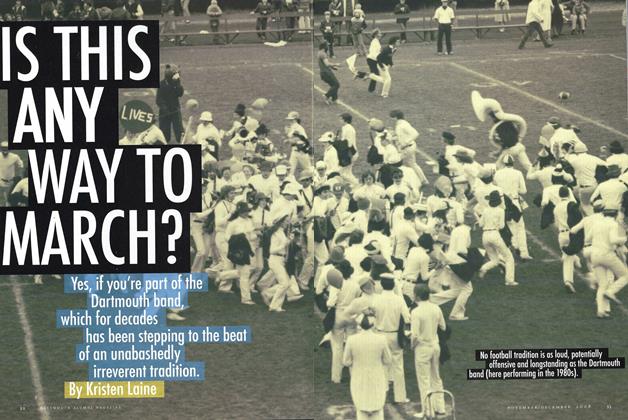

FeatureIs This Any Way To March?

November | December 2008 By Kristen Laine -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2008 By Bruce Beasley '61 -

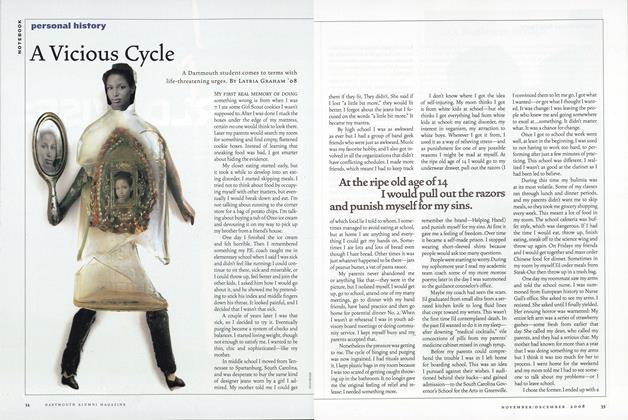

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Vicious Cycle

November | December 2008 By Latria Graham ’08

Ralph Wimbish

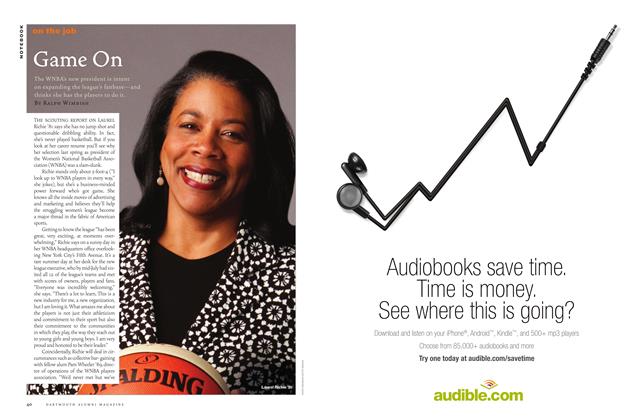

ON THE JOB

-

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBWorking With Obama

May/June 2009 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBLegal Guardian

May/June 2011 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBData Detectives

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By ERIC SMILLIE ’02 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBTheir Future Is Now

Sept/Oct 2009 By Kaitlin Bell ’05 -

On the Job

On the JobWhere the Lava Flows

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBIn the Zone

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By Sean Plottner