An education professor reports on his efforts to use Shakespearean drama to bring reconciliation to a war-ravaged land.

CANDLES FLICKER IN THE GUTTED WINDOWS. IN THE DARKENED SHELL OF the war-ravaged university library courtyard the boy moves slowly, stealthily toward the girl. All the others—dancers dressed in black trimmed with red—adopt stances of frozen animation. The boy, a smile on his lips, holds the girl's eyes as he approaches her. They meet beneath ribbons cascading from above: palms touch, fingers intertwine. The girl lowers her eyes demurely—just for a moment—then looks up to meet the boy's steady gaze. Their bodies move closer. "If I profane with my unworthiest hand, the gentle sin is this...," says Romeo (16-year-old Dzenan Durakovic) to Juliet (18-yearold Klara Markic) in slightly accented English.

The scene is the Capulet ball in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. Romeo, played by a Muslim Bosniak, is professing his love at first sight of Juliet—in this case a Catholic Croat. What is occurring on stage between the adolescent lovers—and what has happened through five weeks of intense rehearsal—is remarkable. Remarkable because it involves a coming together of teenagers from two formerly warring ethnic groups in this polarized Balkan country. The setting is Mostar, the largest city in southern Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is divided roughly by the Neretva River. With the Muslims on the east and the Catholics on the west, there are few opportunities for social interaction between the two groups. Although it is 11 years since the U.S.-brokered Dayton Agreement put an end to civil war in the Balkans, hostilities run deep and ethnic tensions persist. Schools throughout the country are segregated, and ideas that encourage cross-cultural collaboration are viewed with suspicion.

For the last seven years, with teams of Dartmouth graduate and undergraduate researchers, I have been exploring the painful transition toward desegregation in two Mostar-area schools. I have also been studying the impact of the war on the moral reasoning

of children and adolescents, their attitudes about forgiveness and their development of faith. I viewed my role in producing Romeo and Juliet as a token of my thanks to the city's youth for their cooperation in my research, but it was also an explicit intervention that I hoped would help reconcile antagonistic neighbors.

Producing a play in current-day Bosnia and Herzegovina presented particular challenges due to the nations fragile ethnic relations and recent violent history. Upwards of 250,000 Bosnians perished in the largest conflict in Europe since World War II, and more than a million were displaced. Living in the shadow of the atrocities committed between 1992 and 1995, the citizens of this reconfigured nation now face the challenge of how to reject the nationalistic platforms of their politicians, move forward with their lives and find some way to coexist peaceably with their neighbors—all the while not losing sight of the lessons of the past.

But how can a countiy hold together if its students cannot learn together and play in harmony, and especially if some identify more strongly with neighboring Croatia than they do with their own nation of Bosnia and Herzegovina? "My identity is Croat, my nationality is Croat," one young male actor commented. "I've always considered myself a Croat. I want to go to Croatia because I want to be a citizen of Croatia. I want to live and make a family in Croatia. Here, if you go to a Bosniak area, they are different." Part of that difference may be that the Bosniaks primary allegiance is to Bosnia and Herzegovina and that they want to retain the integrity of their country. Many fear the possibility of war breaking out again.

Despite these ethnic divisions, we forged ahead with our play. Two former luminaries in Dartmouth's theater department, Caz Liske '04 and Sabrina Peric '03, played pivotal roles on the production team: Liske, currently a third-year drama student at the Moscow Arts Theater School, as assistant director, and Peric, a second-year doctoral student in anthropology at Harvard University, as designer. They were joined by Emilie Brothers, a McGill graduate who teaches in inner-city London, and Lucy Whidden '07.

We received repeated warnings that our production would attract neither actors nor an audience, and that its theme of feuding families was too painfully relevant to the local context. Instead, Romeoand Juliet drew more than 130 to audition for its integrated cast and crew and it played to four enthusiastic houses in the hot days of early August.

Finding the right location provided one of the bigger challenges. I looked for an open-air setting that was austere and evocative—one that could suggest Shakespeare's Verona, with its bustling courtyards and political intrigues, and also reflect Mostars grand past. The ruins of the old university library, built in the last decade of the 19th century and the home of a former mayor, served as awelcoming meeting place for our cast and crew.

It was not only the presence of mines, the shrapnel-scarred sidewalks or the broken buildings that spoke of human tragedy and dislocated lives. On the last night of the production, as the Friar confided in Juliet about the magical properties of some herbs, a man of approximately 30, dressed in street clothes, suddenly stood in the main entrance of the library, fully illuminated at center stage. He looked bemused rather than drunk as he stared down into the rapt audience. I signaled to some cast members to coax him off the stage, but to do so respectfully, lest he turn violent. I need not have worried; quietly weeping, the unexpected visitor told my Capulet offstage that during the war he had fought near the library and had lost two brothers in the conflict. A probable victim of post-traumatic stress disorder, he pleaded with my actors to hear his story. "People like him did something that nobody appreciates," one actor said to me. "They fought for something and yet they really don't know what they fought for, and after the war nobody remembers them. Nobody wants to hear their story."

In this atmosphere of mutual suspicion, striving to make the student actors into a cohesive group was also a significant challenge. Initially there was some disagreement about what language would be spoken in the play. I had decided that 80 percent of the text would be rendered in the languages of the two ethnic groups and 20 percent would be in Shakespearean English. Disagreements developed about which parts should be in Croatian or Bosnian. Peric, who has Croatian roots, was a tremendous help in resolving these discussions, and after five weeks together all the cast members simply referred to "our language."

At one rehearsal Lady Capulet, played by a Muslim, and Paris, who was played by a Catholic, were mysteriously absent. We later learned they had been on a date, and that Lady Capulet had taken Paris across the Stari Most bridge to the eastern side of the river—the first visit in his 18 years to the Muslim side of his home city.

Acting workshops run by Liske, pizza parties, soccer games in the park and trips to the ravishing Croatian coast all helped meld the disparate individuals into a team. It became clear that attitudes and lives were being transformed by this artistic collaboration. "I am glad that Romeo is a Muslim and I am a Christian. It is good to show the city that different people can work together for this play," said Markic, our Juliet. As we prepared to depart there were many signs of hope, and the young actors were clamoring for the Dartmouth team to return the following summer.

All the World's a Stage Performers overcame ethnic differences and joined together for a unique theatrical experience.

ANDREW GARROD directs the teacher education program at Dartmouth.

"We received repeated warnings that our production would attract neither actors nor an audience.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

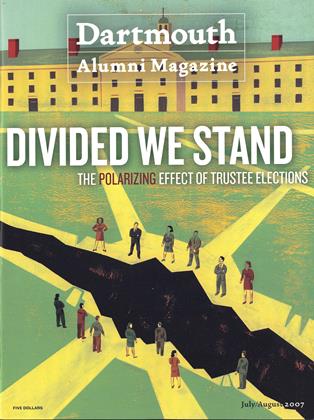

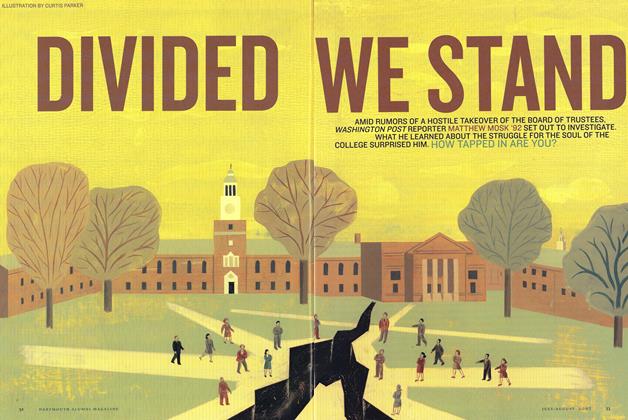

Cover Story

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July | August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

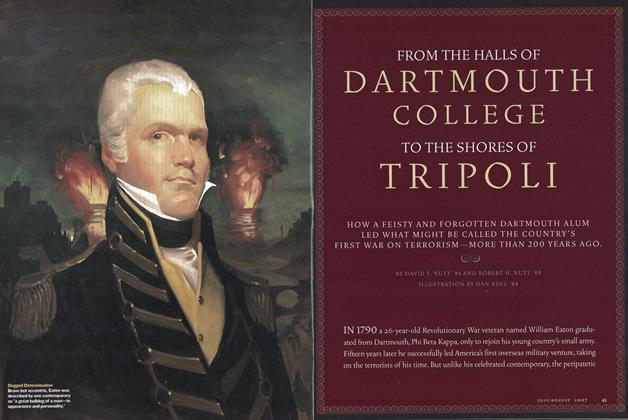

Feature

FeatureFrom the Halls of Dartmouth College to the Shores of Tripoli

July | August 2007 By DAVID T. NUTT ’44 AND ROBERT H. NUTT ’49 -

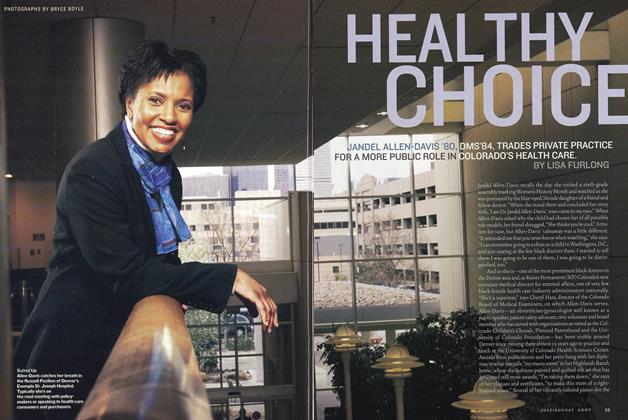

Feature

FeatureHealthy Choice

July | August 2007 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2007 By BONNIE BARBER

Article

-

Article

ArticleVALE ATQUE AVE

June 1917 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH DEGREE IS GOAL OF KOREAN'S AMBITION

August, 1923 -

Article

ArticlePublication Schedule

June 1943 -

Article

ArticleThayer

JANUARY 1973 By J. J. ERMENC -

Article

ArticleWestchester

FEBRUARY 1971 By J. RICHARD PRIOR '60 -

Article

ArticleThe Mystery of the Wah Hoo Wah

March 1974 By JOHN B. STEARNS'16