“I’m Here to Listen”

Dartmouth’s expert on post-traumatic stress disorder discusses the challenges faced by veterans back from Iraq.

Jan/Feb 2008 Nik Steinberg ’02Dartmouth’s expert on post-traumatic stress disorder discusses the challenges faced by veterans back from Iraq.

Jan/Feb 2008 Nik Steinberg ’02Dartmouth's expert on post-traumatic stress disorder discusses the challenges faced by veterans back from Iraq.

In 1973, AS THE LAST U.S. SOLDIERS were withdrawn from Vietnam, Dr. Matthew Friedman '61 left Massachusetts General Hospital to finish his residency in psychiatry at the Veterans Hospital in White River Junction, Vermont. He arrived to a clinic overflowing with combat veterans, their symptoms ranging from vivid flashbacks to violent outbursts. "We didn't know what to do for them," Friedman says.

Few doctors, however, were better suited to understand the veterans than Friedman, whose doctoral dissertation at the University of Kentucky focused on how experiences alter brain structure and behavior. At the VA hospital he found veterans struggling to adapt to such drastic neurological changes. He also found his research partner and future wife in nurse Gayle Smith, who was working there after spending a year at a MASH clinic in South Vietnam. In 1974 he and Smith started, in their apartment, one of the nation's first informal therapy groups for veterans. When Congress established community-based veterans centers in 1979, Friedman was picked to run the first one, in Williston, Vermont.

A decade later a proposal he coauthored established the National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a consortium of seven branches that Friedman directs to this day. In addition to managing more than 100 staff nationwide and a $30 million annual budget, Friedman collaborates with the Department of Defense on preparing soldiers for war, lobbies Congress and the White House to secure adequate funding for treatment, sees patients and teaches Dartmouth medical students. PAW was grateful to get some of his time in early fall to discuss his work.

What is it about combat in Iraq and Afghanistan that makes soldiers susceptible to PTSD?

Many of our current combatants are on their fourth deployment, so we have to wonder whether more exposure is going to be a problem down the road. In Vietnam most of the fighting was at night and there was downtime in the day. The danger in Iraq is an intense 24/7 scenario. Thanks to marvelous surgical capability we're saving a lot more lives. In previous wars 25 percent of people wounded in battle did not survive their wounds. Now it's down to 10 percent. But one of the best predictors of PTSD is sustaining a serious wound.

How does the rate of PTSD among female soldiers compare to males?

Almost all epidemiological research on psychiatric disorders shows that females are nearly twice as likely as men to develop PTSD, depression and other anxiety disorders. Males are more likely to develop alcoholism and substance abuse. However, the data coming out of Iraq is interesting because the men and women are coping about the same. One has to be cautious, because women who enlist in the military may not be representative of American women in general. Whatever is happening, the usual gender difference does not seem to be holding.

Why did you tell Congress that one ofyour greatest concerns was the prevalence of military sexual trauma—thearmed forces' term for sexual assaultand rape?

Military sexual trauma is a terrible thing. It often happens when there's a power im balance, in that the perpetrator is a senior officer compared to the victim. And given the very high emphasis on group cohesion and loyalty in the military, there's real pressure on people who have been sexually traumatized to keep their mouths shut. It's even more complicated in a war zone, because you are all dependent on one another for safety and staying alive. So it's very difficult for victims to come forward, especially if they are women, who are the minority and may feel the need to prove themselves more than men. You may not be aware that there are as many males with military sexual trauma as females. Even though the proportion is higher for females, it comes out to about the same number.

Why are the soldiers in need of treatment the least likely to seek it?

In our society there is a stigma associated with mental illness. That stigma is amplified in a military culture, where having mental illness is seen as not having the right stuff. Even when people recognize they are not the same as they were before their deployment, they may hesitate to seek mental health treatment because they're afraid it will ruin their career. Remember, we have an all-volunteer army, and many of these people were thinking of spending 20 years or more in the military. Another reason is that avoidance is one of PTSD's main symptoms. People don't want to have to confront their traumatic memories because it's too painful.

What's your most memorable PTSDexperience?

About 20 years ago I got a call from the emergency room saying that a Vietnam veteran just showed up holding a rifle and insisted on seeing a psychiatrist. I told the ER to call the police but to tell them to stay out of sight. So there I was, driving to the ER through the snow, thinking: Here's a guy who's driven in the middle of the night, with a gun, to see a psychiatrist. He obviously wants help or he wouldn't have done this. When I arrived I made sure that the police were out of sight, and there's the guy with a gun. I went up to him and said, "Look, I'm here to listen to you, but I'm so scared because you're holding that gun that I don't think I can in these conditions. So if you're willing to relinquish your weapon, I'm willing to do everything I can to help you." He tossed down the gun and within the flick of an eyelash three police grabbed him. I said to the police, I don't think I'm in danger now. Let me go with this man into an office and we'll close the door, but I want you standing outside in case things get out of control." So we went in and talked. He eventually checked in to the hospital, where he did pretty well. Having a sense of how these people felt helped me come up with a strategy. And obviously it was a successful one or I wouldn't be here to tell you about it.

Is there a downside to this practice?

There's a balance that needs to be maintained if you're doing this work. It's very hard to help people who, through no fault of their own, are suffering. One of the problems when you are working with so much trauma is that you shut down emotionally because it's too difficult to bear. Well, you can't shut down emotionally and do your work as a therapist. The other problem is being overwhelmed by taking in all this trauma. Well, you can't do that either.

What holds your interest after working on PTSD for 35 years?

I really believe the trauma field has everything, from the molecular science to social policy to bioterrorism. The questions it asks are absolutely fundamental, the implications are far-reaching and the possible payoff is spectacular. It's very interesting to listen to the morning news and recognize what they're talking about may affect your day at work, whether it's 9/11 or a school shooting or a tsunami. And then there's the moral dimension of trying to help people who were in the wrong place at the wrong time and are suffering. That's not such a bad thing to be doing with your life and your profession.

Nik Steinberg is pursuing a master's inpublic policy at Harvard's Kennedy School ofGovernment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

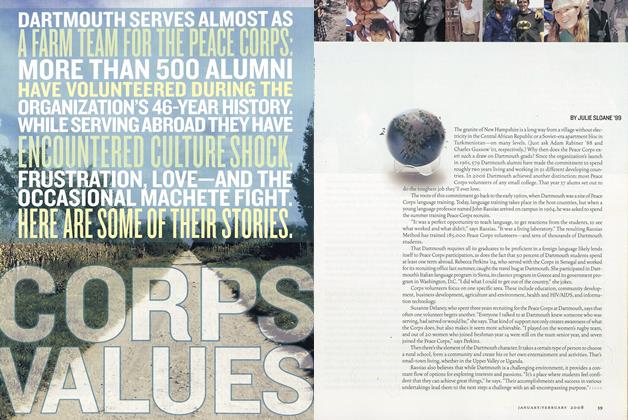

Cover StoryCorps Values

January | February 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

FeatureCold Warrior

January | February 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

FeatureRhyme and Reason

January | February 2008 By CARL JAPIKSE ’69 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

January | February 2008 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

January | February 2008 By Cameron Myler '92 -

Sports

SportsFast Break

January | February 2008 By Mike O’Connell ’65

Interviews

-

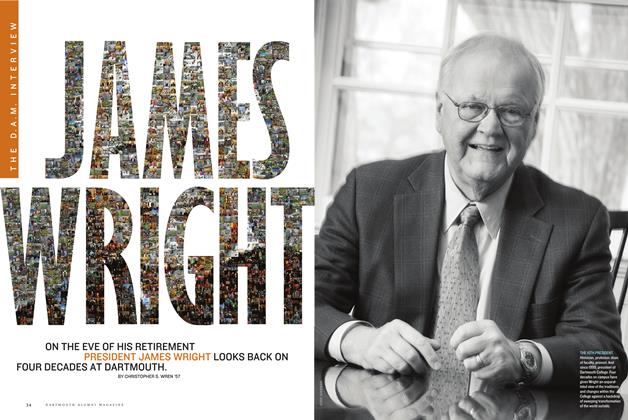

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJames Wright

May/June 2009 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Interview

Interview"We Expect Excellence"

May/June 2005 By James Wright -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

Mar/Apr 2008 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

Interview"Nuanced Decisions"

May/June 2011 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

Interview“The Courage to be New”

Mar/Apr 2003 By Roxanne Khamsi ’02 -

Interview

Interview“Oscar Night Is a Work Night”

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By Sean Plottner