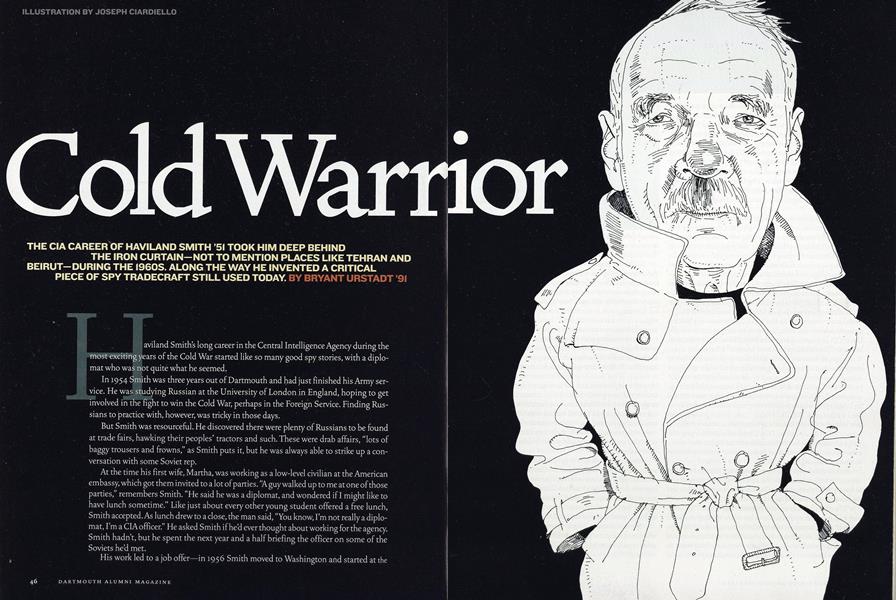

Cold Warrior

The CIA career of Haviland Smith ’51 took him deep behind the Iron Curtain—not to mention places like Tehran and Beirut—during the 1960s. Along the way he invented a critical piece of spy tradecraft still used today.

Jan/Feb 2008 BRYANT URSTADT ’91The CIA career of Haviland Smith ’51 took him deep behind the Iron Curtain—not to mention places like Tehran and Beirut—during the 1960s. Along the way he invented a critical piece of spy tradecraft still used today.

Jan/Feb 2008 BRYANT URSTADT ’91THE CIA CAREER OF HAVILAND SMITH '51 TOOK HIM DEEP BEHIND THE IRON CURTAIN-NOT TO MENTION PLACES LIKE TEHRAN AND BEIRUT-DURING THE 1960S. ALONG THE WAY HE INVENTED A CRITICAL PIECE OF SPY TRADECRAFT STILL USED TODAY.

In 1954 Smith was three years out of Dartmouth and had just finished his Army service. He was studying Russian at the University of London in England, hoping to get involved in the fight to win the Cold War, perhaps in the Foreign Service. Finding Russians to practice with, however, was tricky in those days.

But Smith was resourceful. He discovered there were plenty of Russians to be found at trade fairs, hawking their peoples' tractors and such. These were drab affairs, "lots of baggy trousers and frowns," as Smith puts it, but he was always able to strike up a conversation with some Soviet rep.

At the time his first wife, Martha, was working as alow-level civilian at the American embassy, which got them invited to a lot of parties. "A guy walked up to me at one of those parties," remembers Smith. "He said he was a diplomat, and wondered if I might like to have lunch sometime." Like just about every other young student offered a free lunch, Smith accepted. As lunch drew to a close, the man said, "You know, I'm not really a diplomat, I'm a ClA officer." He asked Smith if bed ever thought about working for the agency. Smith hadn't, but he spent the next year and a half briefing the officer on some of the Soviets he'd met.

His work led to a job offer—in 1956 Smith moved to Washington and started at the CIA for $5,000 a year. Not only did it seem like a lot of money, the job accorded nicely with an upbringing that held social service and the public good in high esteem. It was a value prized in his household and also, feels Smith, in the country as a whole at the time.

"There were a lot of us who wanted to save the world who went to work there," he says. "I was one. I really felt that I might contribute to our not being overrun by the Soviets."

As a graduate of the Ivy League, he was hardly alone. The CIA was famously riddled with idealistic Ivy Leaguers, and he met even more officers from Exeter, where he had gone to prep school. There were other Dartmouth grads but, true to form, Smith declines to reveal their names.

Not only did the salary and the philosophy behind it suit him, so did the work. He was in the Clandestine Service, the unit of the CIA dedicated to the recruitment and handling of human sources, as opposed to the Directorate of Intelligence, which primarily prepares reports. The constantly changing assignments and stations fed a restless in quisitiveness and warded off an easy susceptibility to boredom. "I was diagnosed with ADD [attention deficit disorder] when I was 65," says Smith. "The doctor told me that if I'd had any other job I probably would have been an unmitigated disaster."

Smith recalls all this in fairly unassuming guise, considering the kinds of adventures we discuss. Sitting in a corner table at Mollys in Hanover—not exactly Rick's Cafe in Casablanca—he's wearing an argyle sweater vest, a blue button-down shirt and a hat with the letters CIA emblazoned across the front. The acronym is translated below: "The Culinary Institute of America." It's a hat that makes him laugh, so he wears it from time to time. He has gray hair in straight bangs, an unapologetic gray moustache. He talks with quick intensity and often seems amused by the absurdity of the world.

His teeth are all there, too. This would seem an odd footnote, except that he played goalie for Dartmouth's hockey team in 1948 and 1949, in the wild days before the great minds of hockey developed the face mask. "I think," he says, "I was the first goalie to graduate with all my teeth," something he partially attributes to playing backup for an All-American, Dick Desmond 49, which gave him plenty of time on the bench. So much time that he quit after sophomore year, an early sign of what he describes as a lifelong aversion to physical suffering.

Smiths career with the CIA was longer and more fruitful than his stint in hockey. In 1958 he was sent to Prague, where he served as station chief until 1960. The CIA was in relative infancy then, and the Soviet Union was still largely a mystery.

"The cultural divide was just so great," says Smith. "You could pick each other out so easily, but we just knew nothing about one another." Over the years, as officers like Smith matured and the same thing happened on the other side, possibilities for interaction grew greatly, a fact which, in the intelligence world, cut both ways. As Smith sees it, we're in the early stages of a similar trajectory today in our efforts to understand and infiltrate radical Islam.

In Prague Smith was responsible for contact with every agent in Czechoslovakia. He oversaw a staff of one, but his coworker had a nervous breakdown and left soon after Smiths arrival. Then it was just him. That was all right, says Smith, because it was a "limited job. I was just there to support the agents on the other side." Largely, he was a receiver of information, which came by letter and often by "dead drops," packages left in pre-assigned spaces. Through these transmissions, usually from sympathetic officers on the other side, he might learn about troop movements and the names of intelligence officers on the other side. "But we weren't really getting great stuff in those years," he says.

He would take long walks in the old city, too, often tailed by surveillants from Czech intelligence. On those walks he often thought about the art of surveillance and the art of escaping surveillance, and he began to develop some theories of tradecraft later adopted by the CIA as a whole.

In 1960 he moved to Berlin, where he became a case officer in the counterintelligence unit responsible for monitoring east German activities. The job became much more complicated in 1961, when the Berlin Wall went up. Smith remembers that day well. He was in East Berlin and, upon hearing that the Soviets were rolling out concertina wire, he hurried back to his office on the western side of the city. "It was a terrible time," he recalls. "Families were getting split. It was just obvious how bankrupt the Soviet system was."

Communicating with contacts on the other side became one of the major problems in the intelligence business, and it was in Berlin that much of modern intelligence tradecraft was born. As a case officer Smith became responsible for training dozens of agents in the arts of the dead drop and the covert mailing. Tradecraft is beloved in Hollywood, and the dead drop may be the most well-known tool, along with the miniature camera. Smith worked extensively with both. The Soviets were much better at making secret cameras, he says, adding, "All we had were Minoxes, which you could just go out and buy." Smith estimates he must have made more than two dozen dead drops in East Berlin alone in the two years after the wall went up, and probably covertly mailed another three dozen letters.

Returning to the States in 1963, Smith began a three-year stint at Langley as the acting chief of the Czech branch. He set up an internal operations course to teach the elements of communicating with contacts behind the Iron Curtain. In this time he added a major tool to the spy's toolbox. It was called the "brush contact," and it solved one of the persistent problems of the trade: how to exchange information when the CIA officer is being tailed.

"My experience in Prague showed me you can never be sure whether or not you're under surveillance," recalls Smith, "and so I asked myself, 'How can I do what I have to do while I am under surveillance?'

Author Benjamin Weiser first reported on the invention of the brush contact in his 2004 book,A Secret Life, which covers the defection of Polish colonel and U.S. spy Ryszard Kuklinski. Weiser writes: "Smith noticed that when he was in Prague, the MV [Czech secret police] often had four agents follow him—two behind him and two across the street. He found that if he walked along a street and turned right, he created a gap in which the agents trailing him would lose sight of him for a few seconds and those across the street for even longer."

In Prague, Smith had begun to suspect that a second sharp right turn would ensure that both sets of tails would lose visual contact. Passing his contact in that gap, Smith would be able to hand off or receive a packet without detection. And there was another element: There had to be an "escape route," through which the contact agent could disappear before the tails caught up with Smith; otherwise the ruse would be apparent immediately.

Seeking approval for its use, Smith first demonstrated the technique in the reception area of Washington's Mayflower Hotel. With a deputy of Richard Helms, then the CIA deputy director for plans, looking on, Smiths brush contact worked so well that when the deputy asked when the demonstration would begin, he was shocked to learn it had already taken place. The technique was later perfected in New York while Smith was training a Czech agent in communications techniques for his return to Prague. (New York happened to be an active location for spookery of all kinds, due to the presence of the United Nations headquarters.)

The brush contact, writes Weiser, "became one of the most critical forms of CIA tradecraft in the decades that followed." It was used all over Eastern Europe. Prague and Berlin, with their tangled streets, were ideal for Smiths innovation. "It worked like a charm," he says.

Between 1966 and 1969 he was a case officer in Beirut, in charge of efforts against the Soviets and the East Europeans, with three officers working for him. Beirut, famously a great melting pot of intrigue, was "a terrific place to hunt Soviets," says Smith. "It was a wild, free-swinging environment, and our job was to find out who was going crazy and to try to get in touch with them."

There Smith developed friendships with Soviet Bloc contacts and learned something about the art of personal interaction under the communist regime. "They all learned they couldn't trust their peers,' explains Smith, "so they had a problem: how to develop a personal relationship." The answer was a social rite called "bonethrowing," in which one party would throw out a tiny morsel of "sensitive" personal information. If the other returned with something equally sensitive, it was a sign that the two might enter into a relationship. As the friendship grew, so did the mutual compromise, ensuring each against the other.

He developed one friendship in particular with a man named Rem Krasilnikov, then the head of KGB counterintelligence in Beirut. "It was fascinating," says Smith. "We both openly acknowledged that we were intelligence officers, and within the limits of what we could talk about it was actually a very candid relationship." As far as Smith knows it was the only real friendship between members of the CIA and the KGB.

They would have lunch together. Krasilnikov and his wife, Ninel, would come over for dinner. Smith, of course, would have to write up a report about their meal the next day. Krasilnikov was doubtless doing the same.

Smith would sometimes make fun of Rem's first name, which was actually an acronym for "Revolution, Electrification and Peace," a Soviet slogan popular in the 1920s; Krasilnikov's wife's name, similarly patriotic, is Lenin spelled backwards.

In one particularly candid moment the subject of commitment to the revolution came up, and Smith waved Krasilnikov off.

"Oh, stop all the b.s.," Smith said. "You're no more a committed communist than I am."

Krasilnikov argued dutifully, but Smith went on. "In all the years I've been doing this, I've never met one true believer," he said.

Krasilnikov smiled. "The true believers are all in the West," he admitted.

After the 1967 war, however, the party in Beirut ended and "things got tense," says Smith.

In Eastern Europe there had been a kind of gentlemen's agreement that there would be no violence between operatives. "Something had happened early on in Vienna," says Smith, "I'm not sure what, and after that there was a tacit agreement that there wouldn't be any rough stuff." But the Middle East was another story, especially after the Six-Day War in 1967. It was during that period in Beirut that Smith got shot at for the first and last time. He had been asked by the U.S. ambassador to observe the first funeral of a Lebanese member of the militant Palestinian fedayeen. The procession went along the Corniche, a broad boulevard by the Mediterranean. Smith stood on one side, choosing what he thought was an unobtrusive location in the shadow of a wall about 15 feet high. There were mourners and guns everywhere and shots fired in the air. He is still not sure why—perhaps it was just being an American at a Palestinian funeral—but a young teenager on the other side of the boulevard without warning started shooting an AK-47 in Smiths direction. Too small to control the gun's recoil, the boy traced an arc of bullets over Smiths head, finally dislodging a chunk of the wall above him that dropped down his shirt. "It confirmed my deeply held belief that I'm a devout coward," he says, adding that the kind of guy needed in an area like that is more of the special operations variety, such as an Army Ranger, rather than a bookish, desk type such as himself. He kept that bit of stone for years on his bureau.

Smith served as deputy station chief in Tehran from 1969 to 1971—a "terrible tour," he says—and then back at Langley, overseeing worldwide developmental and recruitment operations against Eastern Europeans and Soviets. One of his assignments in those years was to put together a sketch of every Soviet who had ever cooperated with the CIA from 1945 on.There were perhaps 100 names on that list, and it included an examination of the motivations of each one. "Of those, only a handful were actually recruited as agents, most were volunteers," says Smith. "We would try cold pitches—throwing a note into a car or something—and some tried coercion, but it never worked." The CIA, in other words, was at the time less useful as an organization of infiltration than as a global point of entry for any sympathetic "enemy" who might wish to cooperate.

Later Smith became the chief of the counterterrorism staff, over-seeing intelligence on groups such as Italy's Red Brigades, Germany's Baader-Meinhof, Black September, the IRA and the Japanese Red Army. In trying to track down such groups "the key to the whole thing is foreign intelligence," notes Smith, meaning that liaisons with agencies in-country will always provide more valuable intelligence than the CIA could ever dig up on its own. From that practical point of view, recent events, particularly in Iraq, says Smith, "cannot have a good effect on our liaison relationships." The intelligence challenge presented by groups such as Al Qaeda, Smith believes, will ultimately be solved by friendly services in the Middle East.

Smith retired in 1980 and moved to Brookfield, Vermont. He built a house and raised fallow deer, putting up a seven-foot fence around 15 acres of property. At one time he had more than 100 deer, which he sold to restaurants and specialty grocers. In 1999, not long after one of his deer head-butted him and broke two of his ribs, his wife had had it. "You're not going to die on this place, this place is going to kill you," she told him. Soon after they sold the farm and moved to a small condo in nearby Williston, just outside Burlington.

Smith remains a keen watcher of world events. He remembers standing with his wife in front of the TV in Vermont in the fall of 1989, when the Berlin Wall came down, tears in his eyes. "It just blew me away," he says. "I was there the day they put it up, and I never would have thought it would just disappear like that."

He writes now, too, contributing for years to The Burlington FreePress and currently writing regularly for The Baltimore Sun and the Hanover areas Valley News. After Britain's MI-5 successfully disrupted the attempted bombings of several airliners last summer, Smith pointed out the valuable role local intelligence would play in future counterterrorism efforts and urged the United States to consider building a domestic intelligence unit similar to England's. He places op-eds and other pieces as he can. In January of 2005, for instance, he wrote for The Washington Post about the wisdom of punishing the CLA's Clandestine Service for providing pessimistic reports of the situation in Iraq. He's also written for The Boston Globe and The Hartford Courant.

One of his subjects is the "emasculation" of the CIA, a process he says has been progressing steadily since 1990, when budget and personnel were reduced in a "peace dividend" after the Cold War. The 9/11 attacks tarnished the agency's reputation, and "the administration screwed the CIA in terms of blaming it all on them, creating an environment into which everything since 9/11 fit," Smith says. In the run-up to Iraq analysts "who questioned the wisdom of invading Iraq were not allowed to put it forward," he says, and the subsequent environment was one where those analysts, already frustrated by being blamed for 9/11, were more likely to throw up their hands. The intervening years have resulted in a battle between the agency and the administration, resulting in Porter Goss and Gen. Michael V. Hayden, two directors loyal to the administration rather than intelligence, he says. Smith is not optimistic about the changes. "Much of the senior management of the Clandestine Service has been fired or has quit, reportedly to be replaced with more compliant officials," he wrote in The Washington Post. He described the purge as "cutting off our nose to spite our face."

Last summer Hayden announced the release of the much-publicized "family jewels," memos prepared internally by the ClA in the 1970s that documented wrongdoing of all kinds.

"You heard about this stuff," says Smith, "but I wasn't involved in any of it. I was working on the Soviets at the time and if I was asked to do anything illegal, I just refused." As for why Hayden chose to release them now, Smith is not sure. "Maybe the time was just right," he says. "If this had happened 20 years ago there would have been an absolute firestorm."

In any event, says Smith, it is well to remember that, "with the exception of a few things undertaken by Dick Helms [director from 1966 to 1973], pretty much everything the CIA does is ordered by the White House."

In a way, though, Washington seems very far from Smith these days. He points out that he "really has no inside information." He's a Vermonter now.

The Honourable Schoolboy Smith in 1955, one year prior to joining the Agency.

THE CIA WAS FAMOUSLY RIDDLED WITH IDEALISTIC IVY LEAGUERS.THERE WERE OTHER DARTMOUTH GRADS BUT, TRUE TO FORM, SMITH DECLINES TO REVEAL THEIR NAMES.

SMITH'S "BRUSH CONTACT" BECAME ONE OF THE MOSTCRITICAL FORMS OF CIA TRADECRAFT."IT WORKED LIKE A CHARM," HE SAYS.

Bryant Urstadt haswrittenfor Harpers, New York and The New Yorker. He lives in New York City.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

January | February 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

FeatureRhyme and Reason

January | February 2008 By CARL JAPIKSE ’69 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

January | February 2008 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

January | February 2008 By Cameron Myler '92 -

Sports

SportsFast Break

January | February 2008 By Mike O’Connell ’65 -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“I’m Here to Listen”

January | February 2008 By Nik Steinberg ’02

BRYANT URSTADT ’91

-

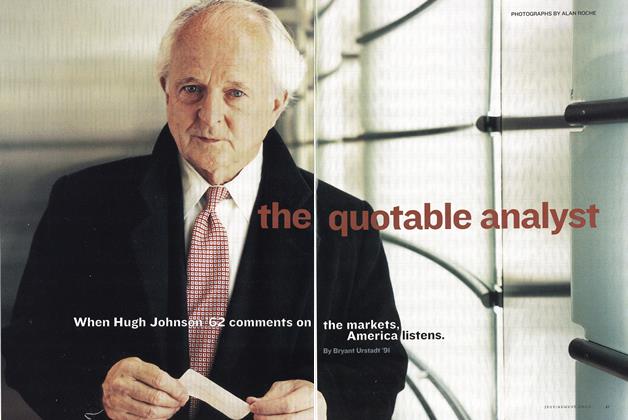

Feature

FeatureThe Quotable Analyst

July/Aug 2002 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

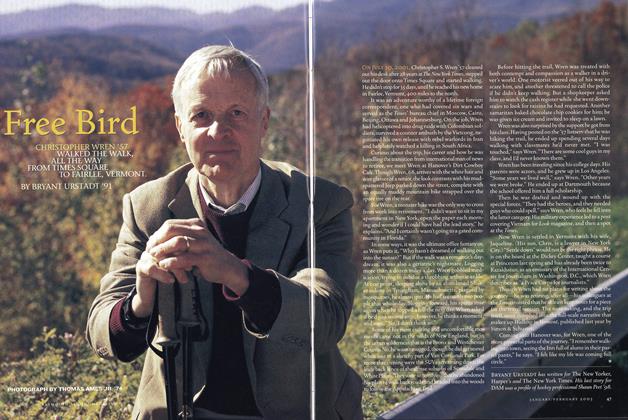

Feature

FeatureFree Bird

Jan/Feb 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

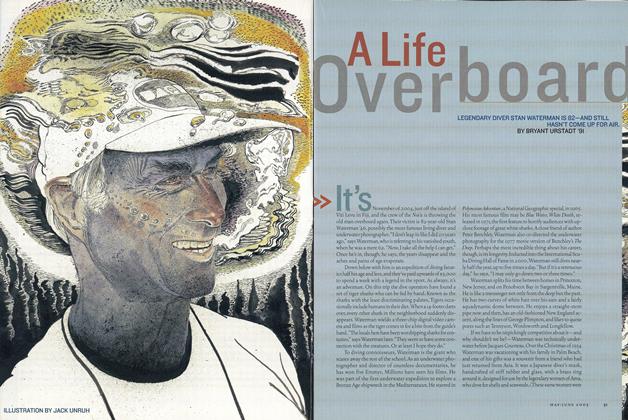

FeatureA Life Overboard

May/June 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Cover Story

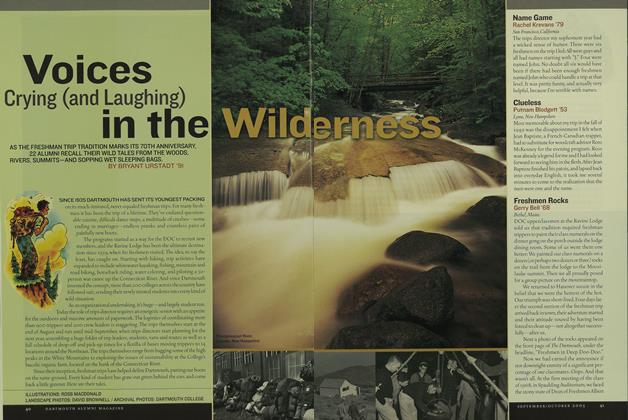

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

Sept/Oct 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

Nov/Dec 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

FACULTY

FACULTY“This Is Gonna Work”

Sept/Oct 2009 By Bryant Urstadt ’91

Features

-

Feature

Feature1960 ALUMNI FUND STATEMENT

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

FeatureThe "Greening" of the NFL

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

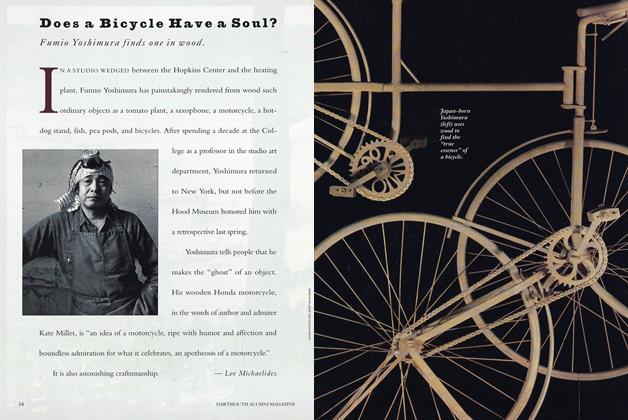

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov - Dec By RR JONES -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

MARCH 1978 By Shelby Grantham