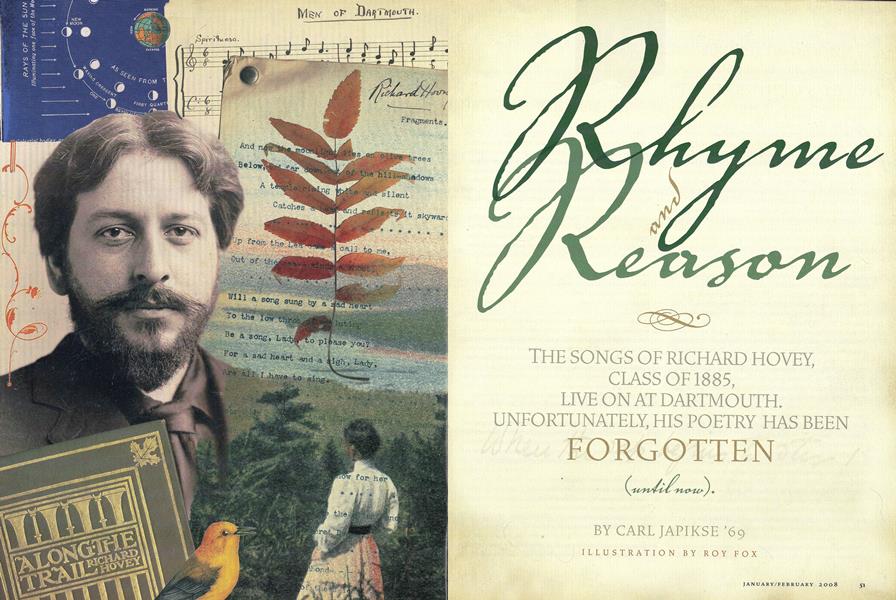

Rhyme and Reason

The songs of Richard Hovey, class of 1885, live on at Dartmouth. Unfortunately, his poetry has been forgotten (until now).

Jan/Feb 2008 CARL JAPIKSE ’69The songs of Richard Hovey, class of 1885, live on at Dartmouth. Unfortunately, his poetry has been forgotten (until now).

Jan/Feb 2008 CARL JAPIKSE ’69THE SONGS OF RICHARD HOVEY, CLASS OF 1885, LIVE ON AT DARTMOUTH. UNFORTUNATELY, HIS POETRY HAS BEEN FORGOTTEN

When Hovey died in 1900 he was on his way to becoming one of the best-loved poets of his day. He had teamed with friend and fellow poet Bliss Carman to issue three volumes of Songs from Vagabondia, which had made him well known to American lovers of poetry. He had also produced two volumes of his more serious poetry, Along the Trail and To the End of the Trail. His poems appeared in major anthologies, textbooks and journals, including the gold standard, Louis Untermeyer's 1919 Anthology of ModernAmerican Poetry.

Today, the trail to Hovey has all but evaporated. Even at his alma mater, where his words are still sung, he's been forgotten as a poet. His poems cannot be found in any anthology of American poetry published in the last 75 years.

Yet he wrote more than 130 poems and published seven books, five of which are poetry collections. He sold more than 11,000 copies of Songsfrom Vagabondia, a good number for a poetry book. Two reasons seem to explain why his reputation did not endure: His untimely death just as his reputation was solidifying (he died on an operating table while undergoing minor surgery), and the shifting tastes in poetry that led to a preference for more modern poets, such as Sylvia Plath, Ezra Pound and Allen Ginsberg.

Years later, as a publisher, I assembled a collection of poems about the spiritual dimensions of life. In my research I stumbled across two quatrains by Hovey, "Immanence" and "Transcendence." I was deeply impressed by the capacity of any poet to capture the infinite nature of the divine in four lines. I included the poems in my collection, but gave Hovey no further thought.

A few years ago, however, I came across Along the Trail while rummaging through rare books. I bought it and started reading Hovey as a serious pursuit. Since then I have added all of his books to my collection. I have also come to the conclusion that the obscurity to which Hovey has been consigned is undeserved.

Hovey s work is charming, witty, joyful, insightful and melodic. Whatever your taste in poetry may be—including none at all—chances are high that Hovey wrote something that will appeal to you. His repertoire ranges from drinking songs to old Norse ballads to odes to fauns and tributes to Dartmouth. His longest poem, "Don Juan: Canto XVII," is one of the finest parodies ever written in the English tongue. It deftly skewers Lord Byron on his own canards.

Not every poem written by Hovey is a gem. But 15 or 20 of them are, in my opinion, worthy of inclusion in any serious anthology of American poetry. One is "The Laurel," a lengthy ode to Mary Day Lanier, wife of the poet Sidney Lanier, another excellent American poet who does not deserve the obscurity in which he molders. This poem explores the art of creating—the art of learning to surpass our own limited views and embrace the larger view of divine light:

For surely from the childing nightThat labors in a God's birth-throes,Shall come at last dawn's baby-rose,The potency of perfect light.

Hovey understood "the potency of perfect light" better than all but a handful of British and American poets.

Another first-rate poem is "Shakespeare Himself," written to be read at the 1894 dedication of a new bust of the bard in Lincoln Park, Chicago. The poem bursts forth with three of the most memorable opening lines I have ever read:

The body is no prison where we lieShut out from our true heritage ofsun;It is the wings wherewith the soul mayfly.

The poem proposes that Shakespeare himself was a greater work of creativity than his plays; that to appreciate any high art fully, we must examine the nature of the person who created it. It ends on a note of hope, that this new bust of Shakespeare may serve to awaken the spark of creativity in those who behold it:

Be as a sudden insight of the soulThat makes a darkness into order start,And lift thee up for all men, fair and whole,Till scholar, merchant,farmer, artisan,Seeing, divine beneath the aureoleThe fellow heart and know thee for a man.

As excellent as these poems are, however, Hovey never lost the wit that splashes forth in "Eleazar Wheelock," the fabled story of the founding of Dartmouth "with five hundred gallons of New England rum." True to his Dartmouth heritage, Hovey penned many songs and odes to drinking, reveling, hiking, lovemaking and enjoying life. An example is the "Wander-Lovers," in which he pays tribute to Marna, an ethereal character who appears in many of his poems, representing Hovey's own quest for wandering and discovery:

Down the world with Mama,Daughter of the fire!Mama of the deathless hope,Still alert to win new scopeWhere the wings of life may spreadFor a flight unhazarded!Dreaming of the speech to copeWith the heart's desire!Mama of the far questAfter the divine!

These are poems that make me want to read aloud. They are not the usual dreary stuff of modern poetry, filled with depression, anger and confusion. They are affirmations of light and hope—stirring statements about what is good in men and women, and the sheer elation of living to the fullest. Hovey s genius lies in the depth of his insight into the ineffable joys of living and the graceful elegance with which he translates thought into verse. I believe he rivals John Keats in this regard.

Hovey was an agent of what he called "splendors of unutterable light" in his sonnet "From the Cliff." He lived in two dimensions at once—in the creative spheres of Plato and Shakespeare and Dante as well as in the physical orbs of Hanover and Manhattan, where he taught at Columbia University. His goal as a poet was to show the rest of us how to find the trail that connects the mundane to the creative and tread it along with him. In true Dartmouth fashion he was looking for companions to make the trek with him.

In Hovey's words, familiar to every graduate of Dartmouth: "Give a rouse, give a rouse, with a will!" The voice that cried out in the wilderness 120 years ago is still enchanting, magical and vital.

HOVEY'S GENIUS LIES IN THE DEPTH OF HIS INSIGHT INTO THE NEFFABLE JOYS OF LIVING.

Carl Japikse, a former editor of The Dartmouth, has started and runsfour publishing houses. The author of more than 60 books, he has issued several poetry volumes, including his latest, The Potency of Perfect Light (Kudzu House), the most complete Hovey poetry collection ever published.Japikse lives with his wife, Rose, in the mountains of northern Georgia.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

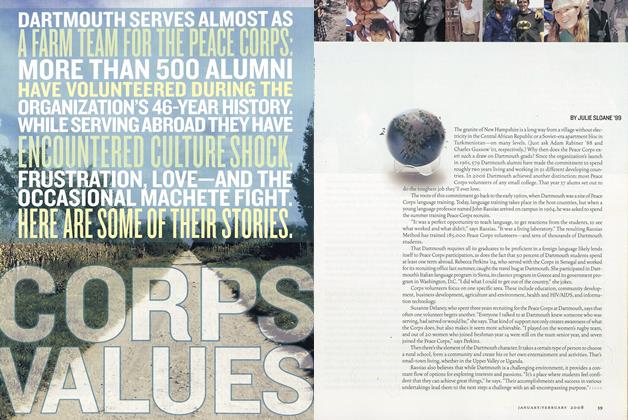

Cover StoryCorps Values

January | February 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

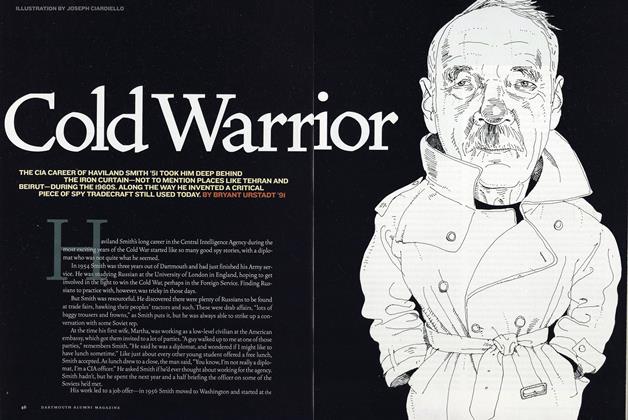

FeatureCold Warrior

January | February 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

January | February 2008 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

January | February 2008 By Cameron Myler '92 -

Sports

SportsFast Break

January | February 2008 By Mike O’Connell ’65 -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“I’m Here to Listen”

January | February 2008 By Nik Steinberg ’02

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobert Swenson '76

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureCue the Millennium

NOVEMBER 1996 -

Feature

FeatureA Three-story House on Bramhall Avenue

May 1979 By Douglas Andrews -

Cover Story

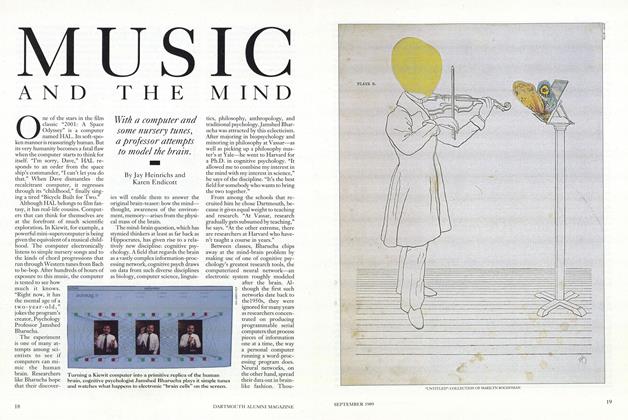

Cover StoryMUSIC AND THE MIND

SEPTEMBER 1989 By Jay Heinrichs and Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Mar/Apr 2012 By Jay Mead '82 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN AN EASY BUCK WITH A CARD TRICK

Sept/Oct 2001 By MICHAEL ELLIS '39