Fast Break

In 1961 hoops player Bobby West ’63 turned his back on Dartmouth, joining the ranks of her immortal runaways.

Jan/Feb 2008 Mike O’Connell ’65In 1961 hoops player Bobby West ’63 turned his back on Dartmouth, joining the ranks of her immortal runaways.

Jan/Feb 2008 Mike O’Connell ’65In 1961 hoops player Bobby West '63 turned his back on Dartmouth, joining the ranks of her immortal runaways.

"Winners never quit, and quiters never win" hardly applies to some of the rogues and renegades who sensed early on that Dartmouth was denying them their destiny, and so skulked or skedaddled out of Hanover way before their time. Only by rejection and retreat could such young men as John Ledyard (class of 1776), Robert Frost (class of 1896) and Fred Rogers '50 be true to themselves and to the enduring Dartmouth values of independence and tenacity of purpose.

On the face of it, Dartmouth of the early 1960s seems like it would have been a hard place to abandon. John Sloan Dickey 29 was still the Colleges revered president, "Bullet Bob" Blackman was the premier coach in the East and quarterback Billy King '63 finished 11th in the Heisman voting. Virility was in vogue—in its college preview edition U.S. News & World Report wrote of Dartmouth: "An athlete with brains will love it."

But after the leaves had fallen from the Balch Hill maples and the strains of Richard Hovey's immortal melodies had died down with the last embers of the Dartmouth Night bonfire, some of the scholar-athletes I knew in the class of 1965 began to contemplate early departure. Some had trouble dealing with Dartmouths demanding academic regimen or its notorious drinking culture or its subarctic isolation. Some were just too far from home. Popular freshman football captain Jim Carr '65 tucked tail for Texas, and some of the rest of us began to imagine what the coeds might be wearing at Auburn or Miami of Ohio or Crossroads Community College.

The published findings of a three-year Dartmouth Medical School study on emotional adjustment and psychiatric treatment included the assertion that Dartmouth students who played on intercollegiate sports teams were less likely to seek psychiatric help than those who didn't. But sports were hardly a panacea. Attrition was worst in the basketball program, which had plummeted from the penthouse to the outhouse following the end of the Rudy Larusso era. An early-season Pea Green win over Holy Cross sparked some talk of a resurgence. But we were crushed in a return match at Worcester, and after that the wheels started to come off.

Unhappy hoopsters from Oregon and Wisconsin failed to return to New England for their sophomore seasons. One player was advised by his psychiatrist to forego varsity basketball. And when the team's best player, Peter Coker '65, left school in early 1963, the rest of us became sleepwalkers on the road to oblivion. Our goal, as it was once defined for us, was to help Hall of Fame coach Alvin "Doggie" Julian obtain his 400th careervictory. But there was some question as to whether that milestone would precede his 400th career loss.

As one who dithered until it was too late, I always had great admiration for the young athlete who, like Ledyard and Frost and Rogers, recognized early on that he was in the wrong place at the wrong time—and got the hell out in time to claim some measure of joy, accomplishment and vindication in friendlier confines. Who would deny that the best thing Larry Bird ever did for himself was to bolt for Terre Haute before the first practice of his freshman year at Indiana University?

And yet from our vantage point in the wilderness such a bold move was fraught with difficulties and Catch-225. Our parents had already invested heavily in our Ivy League education. To cut and run was not only the admission of a big mistake, it also involved a frying-pan-into-the-fire gamble. What makes you think things will go any better at State U. than they did at East Overshoe? Not only will you have to walk on, under NCAA rules you will have to sit out a year. And .what college coach is going to try to find playing time for a refugee from a third-rate program in New Hampshire whose Ivy League competition, Bill Bradley notwithstanding, is considered rinky-dink?

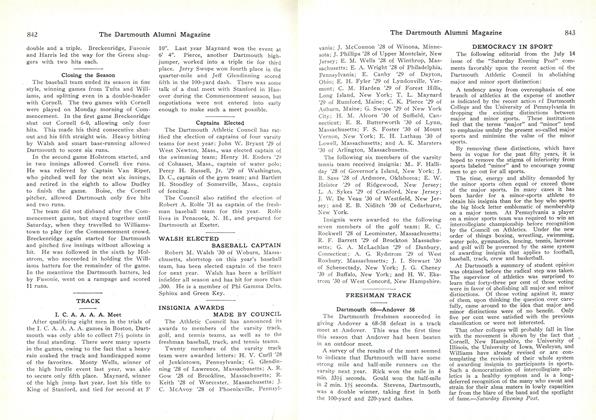

was reminiscing about the dearly departed of recent Dartmouth basketball history. We had heard of the malcontents who, after winning their freshman numerals, had settled for good times in the interfraternity league or around the beer pong tables of Webster Avenue. But Elson had a new story. Two years before, he told us varsity rookies, he had shared playing time with classmate Bobby West, a backcourt whiz long on moxie and short It was on a disastrous Midwestern road trip my sophomore year that good-humored team captain Barry Elson '63 on tolerance for anyone around him who could accept a 5-19 season. West got going when the going got tough—left the team and the school at spring break after the 1960-61 season. His departure secured a starting spot for the reed-like Elson for the next two years.

"He transferred to Bradley," said Elson with a smile.

I came up out of my seat. "Bradley?" I asked. "The Missouri Valley Conference? What made him think he could make it there?"

In the basketball world Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, was everything Dartmouth was not. Ahead of its times in recruiting black athletes, the Braves had twice in the previous decade advanced to the NCAA Final Four. They had won the post-season National Invitational Tour nament in 1957 and 1960, and their 1960 roster included future Harlem Globetrotter Bobby Joe Mason and future NBA all-star Chet "The Jet" Walker. The great Oscar Robertsons 1958-60 University of Cincinnati teams had gone 0-3 in Peoria.

Without knowing the answer I began to see West as a heroic figure, a young man not afraid to cut the cord and chase the dream—a compulsive runaway in the best Dartmouth tradition. I admired him in the same way Frost admired Ledyard and Ledyard admired the Danish explorer Vitus Bering, a living symbol of what Ledyard biographer Bill Gifford '88 describes as the "lone explorer in a small craft, beholden to no one."

Within a week of my hearing about West, the Dartmouth Indians were in Indiana for a drubbing by Butler and Purdue. One afternoon while killing time in a motel room I found a game on TV. The Bradley Braves were about to face the national champion Cincinnati Bearcats in a Missouri Valley Conference matchup. Starting for Cincinnati at guard were returning All-Americans Tony Yates and Tom Thacker. Starting for Bradley, at 6 feet and 160 pounds, was slightly built, rock-hard Bobby West. Like Rogers in his Pittsburgh neighborhood, Frost at the Derry farm and Ledyard at full sail, West had landed exactly where he was supposed to be.

Or so it seemed. Forty years later that telecast seemed almost like a dream, and I began to have doubts about the authenticity of West's resurrection. Had I fallen in love with the story so much that I neglected to research the facts? The underpinning of my Bobby West saga was the brief and flickering image I claimed to have seen on TV in 1963. Why was I watching alone that day, and why couldn't I remember anything about the game it-self? Maybe the announcer had said "Bobby Weston" or "Ronnie West." If there really had been a Bobby West playing for Bradley who's to say it was Barry Elson's former teammate and not an unrelated namesake? Had I created a legend in my own mind?

Seeking validation and risking disillusionment, in July of 2007 I decided to find the real Bobby West or Bobby Wests. A member of the Dartmouth class of 1963 located a Bobby West wearing No. 10 in a 1961 Dartmouth team photo, but the Bradley archives on the Internet did not go back that far. A Dartmouth source provided a Peoria, Illinois, address for a Robert R. West '63, but it turned out that person hadn't lived there since 1965.

The Bradley athletic department gave me a Peoria phone number for a Joe Stowell, a former Bradley player and top recruiter said to be a walking encyclopedia of Bradley basketball. I called him at home on a Saturday morning. He had recently celebrated his 80th birthday, and he spoke with authority.

"Bob West was a pretty good player for us in 1962-63 and 1963-64," he said. "Good shooter, good student, quiet kid."

"Did he transfer in from Dartmouth?" I asked. Stowell asked for a minute to check his files.

"No. As I remember, he came here directly from Peoria Central High School. In fact, I was his freshman coach there." Stowell thought the Bobby West he had known might be in business somewhere in West Virginia.

The Bradley alumni affairs office said they had an address for a Robert West but could not give it out to someone who was not an alum. A staffer offered to forward my e-mail inquiry to him.

An hour later I received an e-mail from Mineral Point, Georgia—from the one and only Bobby West. My fears had been groundless; Stowell's memory had failed him. And the quiet kid who had ditched Dartmouth, graduated from Bradley and received a masters from Purdue was ready to talk about the decision that changed his life.

West, now a retired Bell Labs executive, said he had hoped for a scholarship offer from Bradley coming out of high school, but it hadn't happened. A prominent Peoria businessman who was a Dartmouth grad encouraged him to accept a need-based financial aid offer from the College. "Dartmouth and the Ivy League were very enticing for a Midwest kid with high aspirations," he said. Early on he made some good friends—he still has the tennis racquet given him by Massachusetts Hall roommate Doug Floren '63. "But I never really felt welcome at Dartmouth. Campus life was hard. I had no extra money to spend on the fun stuff, like going for a burger or frappe like most of the others did. At the end of two years I was thousands of dollars in the hole in student loans, and not happy."

Dartmouth's moribund basketball program compounded his misery. A varsity starter as a sophomore and a keen student of the game, West did not accept the conventional wisdom that Dartmouth just didn't have the horses: "I remember a team that usually lost not due to a lack of skill but instead a lack of conditioning and preparedness."

Back home in Illinois the summer following his freshman year, West met a Bradley student named Janet Whitehall and fell in love. "When I went back to Hanover that fall I missed her greatly. But the biggest reason I left Dartmouth is this: We went to Peoria to play Bradley my sophomore year. Bradley clobbered us, but I had a good game. At a party after the game I ran into the Bradley coach [Chuck Orsborn] and he said he had made a mistake in not recruiting me, and if I decided to come back he would give me a full scholarship. I finished the winter trimester at Dartmouth, transferred to Bradley and never looked back."

Playing one of the toughest schedules in the country, Bradley went 17-9 in 1962. In 1964, while Dartmouth was going 2-23, the Braves soared to 23-6 in a season that included a road win at Cincinnati. They climaxed their season by trouncing New Mexico to win the NIT in Madison Square Garden.

That night in the locker room the game ball was awarded to Bobby West, future member of the Bradley Athletic Hall of Fame and the Illinois State Basketball Coaches Hall of Fame.

Outta Here Onlyafter transferringto Bradley did Westbecome a star.

From our vantage pointsuch a bold move was fraughtwith difficulties and Catch-22s.

Mike O'Connell is a part-time Englishlecturer at the University of Wisconsin Barabooand Richland campuses.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

January | February 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

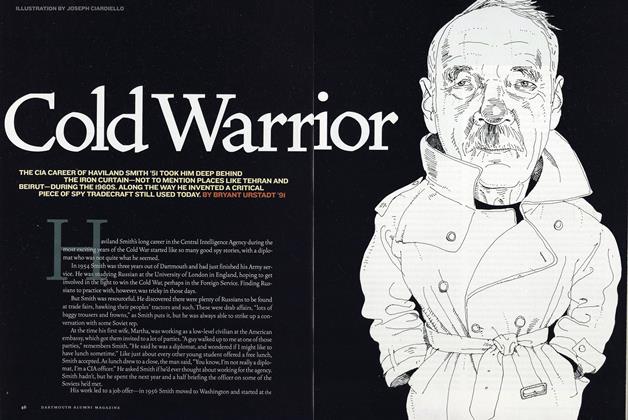

FeatureCold Warrior

January | February 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

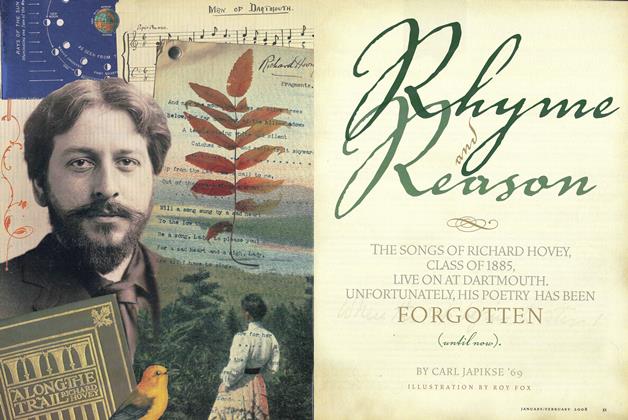

FeatureRhyme and Reason

January | February 2008 By CARL JAPIKSE ’69 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

January | February 2008 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

January | February 2008 By Cameron Myler '92 -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“I’m Here to Listen”

January | February 2008 By Nik Steinberg ’02

Sports

-

Sports

SportsBaseball's Sweet Moments of May

June • 1988 -

Sports

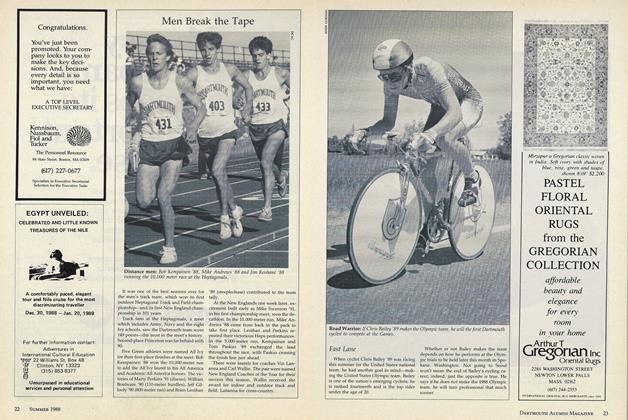

SportsFast Lane

June • 1988 -

Sports

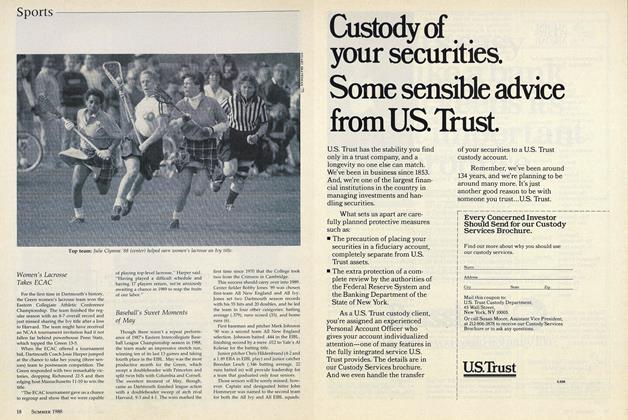

SportsDistant Replay

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2019 -

Sports

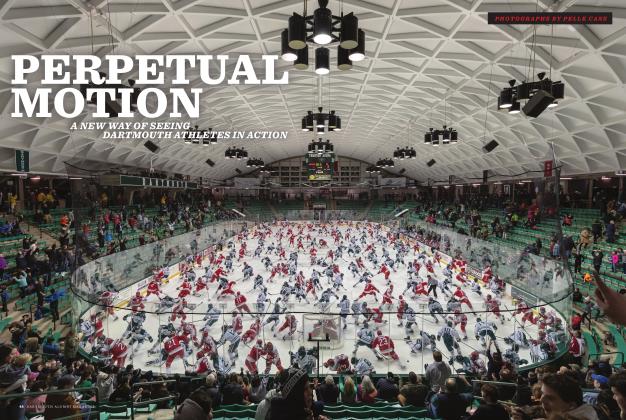

SportsPerpetual Motion

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2019 -

SPORTS

SPORTS“A Dark Hole”

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By ADAM ESTOCLET '11 -

Sports

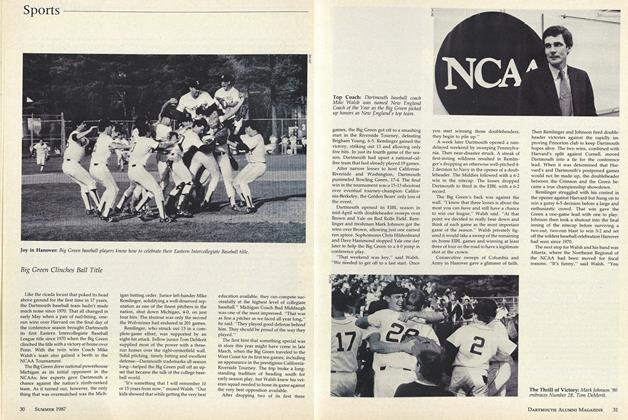

SportsBig Green Clinches Ball Title

June 1987 By Bruce Wood