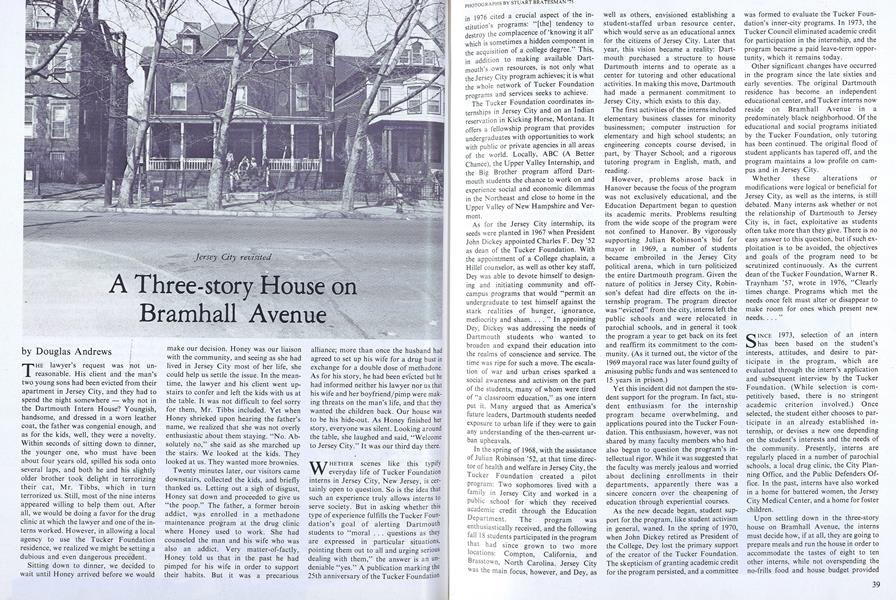

Jersey City revisited

THE lawyer's request was not unreasonable. His client and the man's two young sons had been evicted from their apartment in Jersey City, and they had to spend the night somewhere - why not in the Dartmouth Intern House? Youngish, handsome, and dressed in a worn leather coat, the father was congenial enough, and as for the kids, well, they were a novelty. Within seconds of sitting down to dinner, the younger one, who must have been about four years old, spilled his soda onto several laps, and both he and his slightly older brother took delight in terrorizing their cat, Mr. Tibbs, which in turn terrorized us. Still, most of the nine interns appeared willing to help them out. After all, we would be doing a favor for the drug clinic at which the lawyer and one of the interns worked. However, in allowing a local agency to use the Tucker Foundation residence, we realized we might be setting a dubious and even dangerous precedent.

Sitting down to dinner, we decided to wait until Honey arrived before we would make our decision. Honey was our liaison with the community, and seeing as she had lived in Jersey City most of her life, she could help us settle the issue. In the meantime, the lawyer and his client went upstairs to confer and left the kids with us at the table. It was not difficult to feel sorry for them, Mr. Tibbs included. Yet when Honey shrieked upon hearing the father's name, we realized that she was not overly enthusiastic about them staying. "No. Absolutely no," she said as she marched up the stairs. We looked at the kids. They looked at us. They wanted more brownies.

Twenty minutes later, our visitors came downstairs, collected the kids, and briefly thanked us. Letting out a sigh of disgust, Honey sat down arid proceeded to give us "the poop." The father, a former heroin- addict, was enrolled in a methadone maintenance program at the drug clinic where Honey used to work. She had counseled the man and his wife who was also an addict. Very matter-of-factly, Honey told us that in the past he had pimped for his wife in order to support their habits. But it was a precarious alliance; more than once the husband had agreed to set up his wife for a drug bust in exchange for a double dose of methadone. As for his story, he had been evicted but he had informed neither his lawyer nor us that his wife and her boyfriend/pimp were making threats on the man's life, and that they wanted the children back. Our house was to be his hide-out. As Honey finished her story, everyone was silent. Looking around the table, she laughed and said, "Welcome to Jersey City." It was our third day there.

WHETHER scenes like this typify everyday life of Tucker Foundation interns in Jersey City, New Jersey, is certainly open to question. So is the idea that such an experience truly allows interns to serve society. But in asking whether this type of experience fulfills the Tucker Foundation's goal of alerting Dartmouth students to "moral . . . questions as they are expressed in particular situations, pointing them out to all and urging serious dealing with them," the answer is an undeniable "yes." A publication marking the 25th anniversary of the Tucker Foundation in 1976 cited a crucial aspect of the institution's programs: "[the] tendency to destroy the complacence of'knowing it all' which is sometimes a hidden component in the acquisition of a college degree." This, in addition to making available Dartmouth's own resources, is not only what the Jersey City program achieves; it is what the whole network of Tucker Foundation programs and services seeks to achieve.

The Tucker Foundation coordinates internships in Jersey City and on an Indian reservation in Kicking Horse, Montana. It offers a fellowship program that provides undergraduates with opportunities to work with public or private agencies in all areas of the world. Locally, ABC (A Better Chance), the Upper Valley Internship, and the Big Brother program afford Dartmouth students the chance to work on and experience social and economic dilemmas in the Northeast and close to home in the Upper Valley of New Hampshire and Vermont.

As for the Jersey City internship, its seeds were planted in 1967 when President John Dickey appointed Charles F. Dey '52 as dean of the Tucker Foundation. With the appointment of a College chaplain, a Hillel counselor, as well as other key staff, Dey was able to devote himself to designing and initiating community and off-campus programs that would "permit an undergraduate to test himself against the stark realities of hunger, ignorance, mediocrity and sham. ..." In appointing Dey, Dickey was addressing the needs of Dartmouth students who wanted to broaden and expand their education into the realms of conscience and service. The time was ripe for such a move. The escalation of war and urban crises sparked a social awareness and activism on the part of the students, many of whom were tired of "a classroom education," as one intern put it. Many argued that as America's future leaders, Dartmouth students needed exposure to urban life if they were to gain any understanding of the then-current urban upheavals.

In the spring of 1968, with the assistance of Julian Robinson '52, at that time director of health and welfare in Jersey City, the Tucker Foundation created a pilot program: Two sophomores lived with a family in Jersey City and worked in a public school for which they received academic credit through the Education Department. The program was enthusiastically received, and the following fall 18 students participated in the program that had since grown to two more locations: Compton, California, and Brasstown, North Carolina. Jersey City was the main focus, however, and Dey, as well as others, envisioned establishing a student-staffed urban resource center, which would serve as an educational annex for the citizens of Jersey City. Later that year, this vision became a reality: Dartmouth purchased a structure to house Dartmouth interns and to operate as a center for tutoring and other educational activities. In making this move, Dartmouth had made a permanent commitment to Jersey City, which exists to this day.

The first activities of the interns included elementary business classes for minority businessmen; computer instruction for elementary and high school students; an engineering concepts course devised, in part, by Thayer School; and a rigorous tutoring program in English, math, and reading.

However, problems arose back in Hanover because the focus of the program was not exclusively educational, and the Education Department began to question its academic merits. Problems resulting from the wide scope of the program were not confined to Hanover. By vigorously supporting Julian Robinson's bid for mayor in 1969, a number of students became embroiled in the Jersey City political arena, which in turn politicized the entire Dartmouth program. Given the nature of politics in Jersey City, Robinson's defeat had dire effects on the internship program. The program director was "evicted" from the city, interns left the public schools and were relocated in parochial schools, and in general it took the program a year to get back on its feet and reaffirm its commitment to the community. (As it turned out, the victor of the 1969 mayoral race was later found guilty of .misusing public funds and was sentenced to 15 years in prison.)

Yet this incident did not dampen the student support for the program. In fact, student enthusiasm for the internship program became overwhelming, and applications poured into the Tucker Foundation. This enthusiasm, however, was not shared by many faculty members who had also begun to question the program's intellectual rigor. While it was suggested that the faculty was merely jealous and worried about declining enrollments in their departments, apparently there was a sincere concern over the cheapening of education through experiential courses.

As the new decade began, student support for the program, like student activism in general, waned. In the spring of 1970, when John Dickey retired as President of the College, Dey lost the primary support of the creator of the Tucker Foundation. The skepticism of granting academic credit for the program persisted, and a committee was formed to evaluate the Tucker Foundation's inner-city programs. In 1973, the Tucker Council eliminated academic credit for participation in the internship, and the program became a paid leave-term opportunity, which it remains today.

Other significant changes have occurred in the program since the late sixties and early seventies. The original Dartmouth residence has become an independent educational center, and Tucker interns now reside on Bramhall Avenue in a predominately black neighborhood. Of the educational and social programs initiated by the Tucker Foundation, only tutoring has been continued. The original flood of student applicants has tapered off, and the program maintains a low profile on campus and in Jersey City.

Whether these alterations or modifications were logical or beneficial for Jersey City, as well as the interns, is still debated. Many interns ask whether or not the relationship of Dartmouth to Jersey City is, in fact, exploitative as students often take more than they give. There is no easy answer to this question, but if such exploitation is to be avoided, the objectives and goals of the program need to be scrutinized continuously. As the current dean of the Tucker Foundation, Warner R. Traynham '57, wrote in 1976, "Clearly times change. Programs which met the needs once felt must alter or disappear to make room for ones which present new needs. ..."

SINCE 1973, selection of an intern has been based on the student's interests, attitudes, and desire to participate in the program, which are evaluated through the intern's application and subsequent interview by the Tucker Foundation. (While selection is competitively based, there is no stringent academic criterion involved.) Once selected, the student either chooses to participate in an already established internship, or devises a new one depending on the student's interests and the needs of the community. Presently, interns are regularly placed in a number of parochial schools, a local drug clinic, the City Planning Office, and the Public Defenders Office. In the past, interns have also worked in a home for battered women, the Jersey City Medical Center, and a home for foster children.

Upon settling down in the three-story house on Bramhall Avenue, the interns must decide how, if at all, they are going to prepare meals and run the house in order to accommodate the tastes of eight to ten other interns, while not overspending the no-frills food and house budget provided by the Tucker Foundation. While the success of this communal living experience varies from term to term, undoubtedly one of the program's values lies in the adjustments and contributions required of each person to make things work and in the personal relationships that develop. For many students who have spent much of their time at Dartmouth staring at the four walls of a dormitory room and taking their meals at Thayer, this experience is invaluable and often wonderful.

We all had a good time [a former intern wrote], and it isn't hard to get me nostalgic about the fall. ... It bothers me a lot that I wouldn't have met these people in Hanover, and that we got along so well out of Hanover. ... It seems ... that I was quite different from the person I am at Dartmouth and I enjoyed it tremendously.

On the other hand, life in the house is not without its problems.

I am really getting paranoid [another intern commented]. In our house we have a large number of gourmet and quasi gourmet cooks, whereas I seem to have fallen into the gourmand category! Consequently, I have a great apprehension regarding food affairs.

While it is the interns themselves who actually run the local program, they receive help and assistance from an internship coordinator, a member of the Jersey City community, and a "live-in alumnus" who serve as liaisons between the interns and the city. Jan Tarjan '74 oversees all internships including the selection of interns and the administration of the program. Honey Kaplan, a long-time resident of Jersey City, is largely responsible for setting up the internships and handling related problems, as well as arranging seminars with community figures. Fred de la Vega '78, on the staff of the City Planning Office, deals with more mundane affairs regarding the house, neighborhood, and city, often serving as the mediating force for conflicts in the house. However, once the term gets underway, the interns are responsible for the running of the house and, more importantly, their internships.

WHILE similar elements may exist, there seems to be only one common experience among interns: the initial emersion into unfamiliar and often unsettling circumstances. Fortunately, this initial taste of the real world does not always give an accurate or definitive picture of what the next three months have in store. If it did, some interns might very well contemplate packing up their bags for Hanover at the end of the first day.

As an example, two interns recently chose to work at a nearby elementary school that traditionally has used interns as teacher assistants. Naturally, there is always some first-day apprehension, but after their first hour the two interns began to wonder what they had gotten themselves into. The principal led them into the classroom of an impressively well behaved fourth-grade class whose teacher was ill that day. The principal instructed the class in religious education for a half an hour with perfect ease and control. "Just have to look like you know what you're doing," she whispered to the interns. By and by, she placed the interns in front of the class and told them to "improvise" as she walked out the door to attend to other matters. Impressed by the principal's example and undaunted by the fact that they had no lesson plan, no knowledge of school rules and regulations, no notion of the class's reading ability, and no conception or understanding of the very different environment of the students, the interns proceeded to "improvise."

Within the three minutes it took the students to recognize that the new teachers indeed knew very little of what they were doing, the students promptly took over control of the class and had a riotous time. There was disco dancing in the aisles, feasts of jelly sandwiches in the back of the room, easily gotten permission for the lavatory, and plenty of chances to show off in front of classmates. So the day went. Exhausted, depressed, and hoarse at the end of school, the interns staggered into the principal's office where they were reassured that "it can only get better." This was indeed true, but the interns could not quite shake off the memory of their inauspicious debut as enlightened educators. This type of experience, while extreme, is not atypical.

I remember my first day [an intern wrote]. I was to take some second grade girls and help them with their math problems. I was about to ask Miss Franklin what I should do with them when she asked me the same question! I had never taught a day in my life.

By no means are all Tucker interns teacher assistants, but their experiences point to many common problems. Not the least of these is the uncertainty one feels in beginning an internship, especially a newly created one. The intern's role is a function of many factors, and it is only after a period of time that all these related forces emerge. The personality and motivation of the intern largely determine the role he or she will adopt. But it is hardly a unilateral decision, as the circumstances into which the intern is thrust, as well as the expectations of the student's co-workers and administrators, which are often based on the performances of previous interns, are equally important. Roles vary greatly. Some interns shoulder startling amounts of responsibility, while others are limited merely to reducing their co-workers' clerical work. Yet, most interns are not spared the problems Jersey City people face every day, whether sexism and racism in the courts or the social and economic obstacles that hinder social and educational services.

Problems on the job are often of a more personal nature. In the case of the two interns who encountered the fourth grade, things quickly improved once they learned the ropes in the school. But they soon found that they, along with their coworkers, had another problem: an often dictatorial administration that dominated the classroom teaching and extracurricular activities. Several times the projects of the Dartmouth students, ranging from a school play to intramural sports, were either short-circuited by the administration or exploited as a means of punishment and reward for students - a purpose completely antithetical to the interns' intentions.

Differences of opinion between interns and their bosses are, of course, inevitable. Perhaps they are best characterized as conflicts between the intern's idealism and the boss's experience. Often interns must indeed give way to the latter since many if not most interns arrive in Jersey City with no training or experience in the fields in which they work. This inexperience, often coupled with a naivete concerning urban life, poses a question: What business do Dartmouth students have in meddling with the lives of people in Jersey City? Any Dartmouth student who would thrust himself or herself into the lives of others in the name of "social service" must ponder this question and its implications. While no answer is readily forthcoming, Charles Dey once observed that "One does not lightly intervene in the life of an inner city, a Southern college, or a 14 year old. The stakes are high and students must know In this regard, one intern wrote, "I felt like an intruder in many ways, for I knew that no matter how involved I might become with the people I met, I could always walk right out at the end of term."

"End of term" is a phenomenon few Jersey City residents can conceptualize or appreciate; a time to put aside the problems of the last three months and look forward to new undertakings. This is indeed a luxury little understood by an elementary student who has become attached to and even dependent on an intern. Stepping into a child's life for three months, becoming an integral part of it, and then leaving one day, most likely never to return for any length of time, seems a dubious way of helping a child. This is not to suggest that an intern should not try to help a child, but that the intern must very carefully consider the impact he or she makes on a child. (One must also consider what impact the intern makes on the children that he or she cannot or chooses not to "help." What do these children think when they see an intern paying attention to their classmates but not them?) For the interns who, with good intentions, come to Jersey City with expectations of producing transformations in the lives they touch, the end of term is a sad time, too, but the real price is paid by those who have come to rely on them for instruction, attention, and even love.

Not to paint too maudlin a picture however - by no means do all interns intend to change the world. They do not all dramatically affect others' lives, be it for better or for worse. A term spent working at a school, hospital, or legal clinic looks good on a professional school application, and Dartmouth students are aware of this. While it is unfair to suggest that most interns' motivations are professionally oriented, it does appear that their reasons for going to Jersey City are more and more based on the experience to be had, as opposed to effecting monumental change. Also, the $500-5600 stipend is a mildly attractive aspect of the internship, but most likely this is not the key motivation since a Dartmouth student can easily earn more by holding a job for an equal amount of time. IF there is one overriding motivation among Dartmouth students to participate in this program it would seem to be a desire to shake things up a bit; to shed one's naivete by experiencing the severe social and urban dilemmas that are studied and speculated upon at Dartmouth, but from which the Dartmouth community is comfortably insulated. There are plenty of these dilemmas to experience in Jersey City, as one intern made clear:

I saw for the first time what a slum can be. Their apartment had no glass in the windows, no kitchen, an open fire in a large can, bare mattresses all over, and huge piles of filthy clothes. It was a total disaster. The mother was passed out on one of the "beds" and came to only long enough to sign a permission slip.

It is difficult to imagine an intern in Jersey City not gaining some insight into the immense urban woes that exist or not realizing the presumptuousness of expecting three months of work to make a significant difference.

Thus, is the shock factor of living in the midst of urban troubles the major value of the Jersey City Internship program? Perhaps, but simply opening one's eyes does not seem a worthy or suitable legacy of the involvement and ambitiousness of the sixties and early seventies. As one intern put it:

I suppose that consciousness-raising is an effort towards a better world somewhere in a far distant future. I find very little attraction in that. I guess that is the ultimate heroism - working so anonymously for something you'll never see. I can't help but see it as the ultimate folly.

Yet a significant number of former interns, including those in recent classes, return to Jersey City to continue working in schools, city hall, and law firms. Many of them have been there for years. Whether this is simply a result of a noblesse oblige sensibility or white upper-middle-class guilt is debatable. But their return is somehow encouraging for it may mean that these alumni retain some degree of optimism in regard to the urban woes that so often overwhelm current Jersey City interns. As these alumni assume positions of economic and political influence, the experience and knowledge they gained through living in an inner-city as undergraduates may well assist them in remedying a myriad of woes afflicting America.

Two Jersey City grade school pupils (leftand opposite) among the group beingtutored this spring by Tucker Interns.

Douglas Andrews, a junior, spent fall termof 1978 as a Tucker Intern in Jersey City.Some of the material on the history of theJersey City program came from a formerinternship director's Ph.D. dissertation. The Politics of Conscience: A Case Study of the Tucker Intern Program at Dartmouth College, by Joanna Sternick.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWhen They Resisted

May 1979 By Steven E. Tozer -

Article

ArticleHearts and Minds Study

May 1979 By TIM TAYLOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1979 By WILLIAM A. CARTER -

Article

ArticleJudicial Clerk

May 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927

May 1979 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK

Features

-

Feature

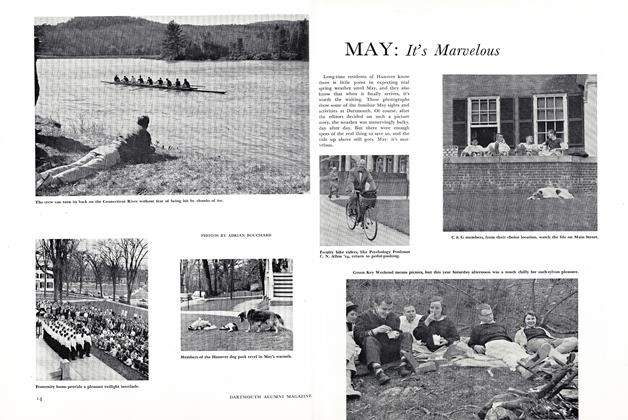

FeatureMAY: It's Marvelous

June 1958 -

Feature

FeatureArcheological "Amateur"

October 1973 -

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

NOVEMBER 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

FeatureThe Debate Over Safe Sex Lands Dartmouth on "Donahue"

APRIL • 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham -

FEATURES

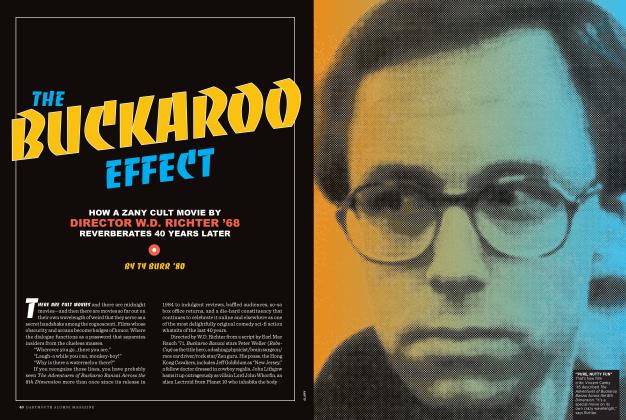

FEATURESThe Buckaroo Effect

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By TY BURR '80