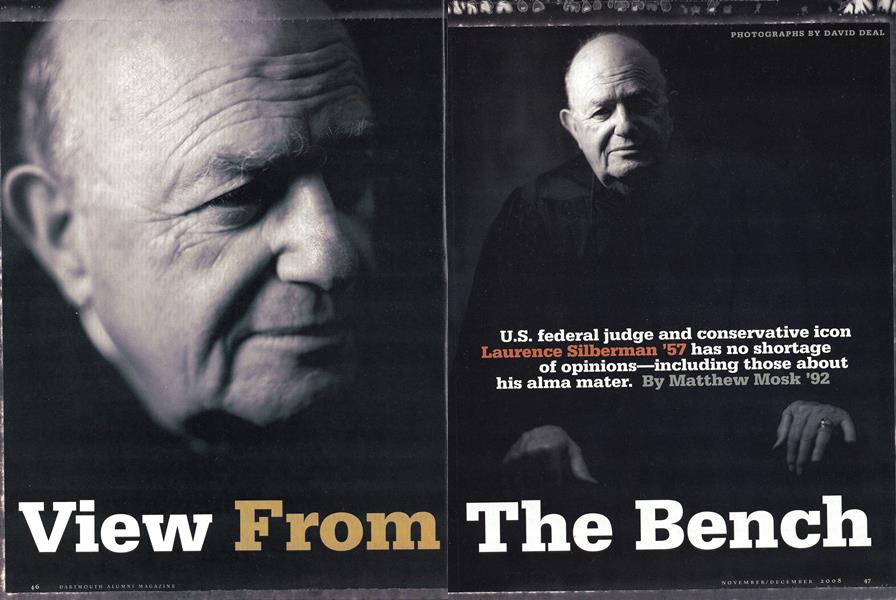

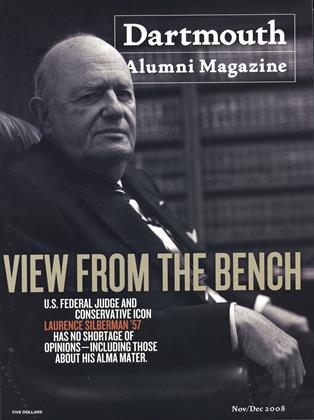

View From the Bench

U.S. federal judge and conservative icon Laurence Silberman ’57 has no shortage of opinions—including those about his alma mater.

Nov/Dec 2008 Matthew Mosk ’92U.S. federal judge and conservative icon Laurence Silberman ’57 has no shortage of opinions—including those about his alma mater.

Nov/Dec 2008 Matthew Mosk ’92U.S. federal judge and conservative icon has no shortage of opinions—including those about his alma mater.

When Judge Laurence H. Silberman got the call in June that hgjwoulci be a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor granted by the government of the United States, he was at first confused—was this a nomination for the medal or was he definitely going to receive it? Such confusion may be understandable from someone who has gotten mixed signals from the White House before. Three times Silberman came just a hair's breadth from being a presidents pick for the U.S. Supreme Court. Instead Silberman has managed just fine from his perch as a senior judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals, a position to which he was appointed in 1985 by President Ronald Reagan after a distinguished government career that included stints at the National Labor Relations Board and the Labor, Justice and State departments.

His has been a recurring name in news out of Washington, D.C. For instance, in 2007 he sent shockwaves across the nation's capital as the author of the landmark court opinion that called the District of Columbia's ban on handguns unconstitutional—an argument adopted by the U.S. Supreme Court last July.

From 2 004 to 2005 Silberman served as co-chair of the Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction, an independent panel that investigated U.S. intelligence surrounding the United States' 2003 invasion of Iraq and Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. Last year he was prominently mentioned as a possible pick for U.S. attorney general when Alberto Gonzales stepped down. (In the interview that follows, Silberman reveals he turned the job down.)

Long a conservative luminary, Silberman has also been a behind-the-scenes force in pushing for change at Dartmouth. As he describes it, he's been a troublemaker for as long as he can remember.

Widowed in February 2007 and remarried since January to wife Patricia, Silberman is the father of Anne Otis, Katherine Silberman Balaban '81 and Robert Silberman 'BO, who is married to Christina Jones Silberman 'Bl. His grandchildren include Robert and Christina's children, Katherine '09 and Christopher 'll. He lives in Washington and sat down in his chambers in July for this interview.

The appeal of your decision rejecting the Washington, D.C.,gun ban, District of Columbia v. Heller, was one of the mostdiscussed Supreme Court cases of the last session. Did youanticipate the outcome?

I was gratified that the Supreme Court affirmed, a little disappointed that there were four dissenters on both grounds. When the case first came to me I was rather surprised because I had been under the impression from just bits and pieces I had read and something Chief Justice Burger had said that the Second Amendment was a collective right. When I looked into it I concluded to the contrary, as the opinion states. I just did my best to read the law and the Constitution.

Which of your other opinions do you consider the most significant?

Most prominent would be the famous independent counsel case, Morrison v. Olson [which upheld the constitutionality of the Independent Counsel Act], The Supreme Court reversed my majoritu decision 7 to 1. [Justice Antonin] Scalia dissented. [Chief Justice William] Renquist reversed. Most law students and professors are now of the view that I was correct. Unfortunately I think that's because the independent counsel ended up torturing Democrats and Republicans. I'm told that Yale Law School uses the opinion I wrote as the only circuit court case they teach in one course.

Another would be the Oliver North case [United States v. Oliver North, in which North was convicted in connection with the Iran-Contra affair], which is sometimes criticized on the grounds that my judgment was political. I think that's rather amusing because one of the grounds on which I dissented, never challenged by any court—grounds on which those of us on the court of appeals overturned Norths conviction—is that once you give immunized testimony, it cannot be used against you by witnesses in the case or by those on the side of the prosecution. I thought North was entitled to call Ronald Reagan as a witness. The administration was very much against it.

Next would be the Jonathan Jay Pollard case. [Pollard, a civilian intelligence analyst, challenged his conviction on espionage charges. After a plea agreement he was given a life sentence for spying for Israel.] Ruth Ginsberg [then a member of the federal appeals court] joined me in upholding the life sentence, and Stephen Williams [the third member of the court] dissented.

Do you ever look back at a decision and wish you had handledit differently?

Occasionally, when I teach a case that I have decided, I will look at it and quibble a bit around the edges. But I don't think there's ever been a case I have decided that I would go back and change.

Do you ever get hate mail or fan mail?

I get a certain amount of hate mail but I never read it. Nor do I read positive fan mail from non-lawyers. I do read editorial opinions. And Ido hear from law professors occasionally—or from lawyers. It's surprising how relatively little feedback judges get on their opinions. One judge has said the only people he thinks read his opinions are the lawyers in the case and their mothers-in-law.

What are the qualities of a good judge?

First of all, he or she should be fair. Secondly, it's crucially important for a judge to be honest in his or her reasoning. If you read an opinion you should know precisely how the judge reached the decision. The judge has to also deal honestly with precedent or the other materials before the court. It's essential to have a first-class analytical mind.

Also it is essential for an appellate judge to be a good, clear writer and to write his or her own opinions. I don't think a judge can do a good job thinking through an opinion unless he or she is writing it.

It is my firm belief a judge should hold to the notion that there is a right answer to every case. It may be a theoretical right answer. It may be difficult to reach it. But the reason it's important to hold to that notion is that if you believe there is a theoretical right answer to the case before you, you are not tempted as much into the policy realm. If the judge believes there is no right answer, it's easier to say, "Oh gee, I'd like it to come out this way.

Who are your legal idols?

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Felix Frankfurter. Both were advocates of judicial restraint.

There was a period of time where you were mentioned frequentlyas a potential appointee to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Three times—1987,l990 and 1991.

Were you ever brought into the Oval Office to talk to a presidentabout your possible nomination as a justice?

No. Not with the president. It apparently was very close a couple of times. But I never regretted it. In no small part because I've enjoyed my time at the Court of Appeals. Ive loved teaching at Georgetown Law School and episodically at Harvard Law School and NYU. If I had been on the Supreme Court I wouldn't have been able to teach the way that I have. Since I've been on senior status, which means I've reduced my caseload down to 25 percent of what it was, I've doubled my teaching.

What's your philosophy of teaching law?

I utilize the Socratic method. That was the way I was taught in law school. It is not as fashionable today. I may be one of the few professors at Georgetown who uses that in advanced classes, but I'm convinced it is the best method to teach students to think precisely and to think on their feet. I feel very strongly that professors, whether at Dartmouth or in law school, should eschew propaganizing their views, philosophic views, political views. As a judge and a law professor I eschew political questions.

Not too long ago your name was mentioned as a possible U.S.attorney general candidate. Was that ever a serious consideration?

Yes, I was approached the Saturday morning after Al Gonzales had resigned privately Friday night. My then fiancee and now wife, Tricia, who is, incidentally, a Democrat and was a Hillary Clinton supporter but who is not terribly knowledgeable about Washing- ton, came out to our back yard, where I was talking with neighbors through the fence by our pool, to say that I had a phone call from the ex-U.N. ambassador. I walked back to the phone muttering, "Why would John Bolton be calling me at 9 o'clock on a Saturday morning?" She said, "You know, I don't think his name was John." Of course, it was [White House Chief of Staff] Josh Bolton. He asked to talk with me about the post of attorney general. I told him I would think about it and call him back that day. I told him I was newly engaged—at that point we hadn't yet gotten married. He said he knew it and the president and vice president knew it. I called him back about three hours later and said I did not wish to be considered.

Why not?

There were a number of reasons, not the least of which was I didn't want to leave the bench at this point. There wasn't much time left for the administration and it's not a very pleasant atmosphere. I wasn't enamored of the Justice Department at that point.

You've served in several departments of the federal government.How did you become ambassador to Yugoslavia from1975 to 1977?

I was deputy attorney general at the time and President Ford and Secretary Kissinger wanted me to get some foreign policy experience. Kissinger offered me Bonn, the post in Germany, first, but my wife refused to go to Germany. She was afraid that as the first Jewish ambassador to Germany I would be forced to go visit concentration camp sites, and she just could not bear the thought. It s the only time she ever said no. But Yugoslavia was of enormous influence and importance because it was in the seam between NATO and the Warsaw Pact. And I had developed an interest at Dartmouth, thanks to John Adams, who taught modern European history and was particularly enamored with the Balkans and Serbia. I had also visited there on a diplomatic mission when I was undersecretary of labor in the Nixon administration.

Can you tell us about your brush with the 1980 Iran hostage situation and the accusation that, while you were working on then Gov. Ronald Reagan's presidential campaign, there was a secret plan for an October surprise? Some people still believe Reagan's people managed to delay the hostages' release from the U.S. embassy in Tehran just to embarrass President Carter.

One of the things I'm grateful about is that The Washington Post never dignified that story. The only newspaper that wrote about the fanciful allegations was the Miami Herald. And the Los AngelesTimes at one point. A congressional investigation chaired by Rep. Lee Hamilton found there was nothing to the allegations. It's ironic because I was responsible for creating the damn story.

This was 1980. Bill Safire was then a columnist for The NewYork Times. He called me and said he had picked up some information that [Reagan national security advisor] "Bud" McFarlane had picked up a person to come to see [Reagan national security advisor] Dick Allen and me concerning the hostages. So I said, "Yes." I had come back from San Francisco for a meeting of the foreign policy advisors of the Reagan campaign. I was co-chairman of his foreign policy advisors. We were meeting, as I recall, with a group of people on Middle East policy involving Israel and the Palestinian-Iraeli question. McFarlane walked in with a fellow who had been a strong supporter of the shah. He was not an Iranian. I thought he said he was from Morocco.

What happened is that Safire wrote in his column that McFarlane had brought this character to us and we had rejected him. A guy by the name of Alfonso Chardy of the Miami Herald picked this up, twisted it around, and wrote a story strongly suggesting that our approach was to delay the release of the hostages until after the election, which would have been infamous and horribleparticularly horrible to me because my son Bob was an officer on a frigate in the Persian Gulf at that time. I'd like to think I'm a patriot to the core, but I'd cut my throat before I'd endanger my son. It became a political issue and a number of Democrats raised hell about it. The story really got insane. It had George H.W. Bush traveling to Paris to meet with Iranians to hold up the hostages. I mean it was really nuts.

Let's turn to Dartmouth. In the late 1980s you wrote aboutyour concerns with regard to changes at the College.

Not all changes. I wrote an essay for my class reunion book in which I described my approval of coeducation. But I did express some concern about the political correctness and about proportional representation and diversity, which is somewhat ironic because I had much to do with creating affirmative action.

Initially you were an architect of affirmative action from thebench, but you changed your views on that?

Yes, I did. I want a level playing field with respect to merit. All institutions in our society, all educational institutions, have adopted a notion of diversity. It used to be affirmative action but it has shifted to diversity because affirmative action was a term that implies a remedy. Those who were in favor wanted a permanent notion so they came to the term diversity. I'm all in favor of diversity. I just don't want proportional representation.

Do you know if there were quotas at Dartmouth that mighthave affected you?

According to [former Dartmouth President James] Freedman there was a quota against Jews when I applied. I couldn't get too annoyed about it because the grounds for the quota against Jews were precisely the same argument that is presented in favor of a quota or goals for minorities. The argument was that Jews were disproportionately represented in higher education and that was inconsistent with diversity. So Jews were limited to somewhere between 12 and 13 percent, which was far higher than their percentage in the population. The logic of that, which I thought offensive, is exactly the same logic in favor of proportional representation at institutions today.

It's important to recognize that any goal or quota that's being has a correlative negative impact on those who are not covered. But that's not the reason I have come to the view that I was so wrong in my efforts to develop affirmative action. I became convinced it was harmful to the supposed beneficiaries. The cost to Caucasians is trivial, but the harm to the purported beneficiaries is very troubling.

Who or what has informed your views on that?

First of all, Tom Sowell, a great economist. And there's a UCLA professor of law by the name of Richard Sander who has written two very powerful law review articles. Interestingly enough he has a half African-American child. When he started out writing to defend affirmative action or diversity he wrote an article in the StanfordLaw Review in which he discussed the impact of affirmative actioin, or preference is the better term, for minorities. He established that it was in fact terribly harmful—that minorities who entered into university law schools at a level somewhat above where their qualifications would have put them are harmed by it. And those who end up in schools that are congruent with their qualifications may tend to really blossom. His second article appeared in DukeLaw Journal just last year and studied the impact of these persons who were beneficiaries of preferences when they got to law firms. His first article pointed out there was a disastrous dropout rate and flunking of the bar. His second article dealt with flunking of the bar and performance in law firms.

You also expressed concern about repression of free speech at Dartmouth. How did you know that was happening?

It was hard not to know what was going on at Dartmouth. Political correctness was sweeping the universities generally. It has receded significantly. I think President Wright has dialed that back quite significantly. But there was a time when Dartmouth and other colleges and universities were, in my judgment, actively discouraging free speech. I thought that was profoundly wrong.

Was the The Dartmouth Review a positive influence on theCollege?

Yes. I thought its writers were in some respects sophomoric but after all, they were sophomores. They were sometimes cruel, but I think The Washington Post is often cruel. I had been a partner in a law firm that specialized in representing newspapers, Morrison & Foerster, and we had been zealous defend- ers of the First Amendment and First Amendment values. It was hard not to learn about what was going on at Dartmouth in those days, particularly under President Freedman, as well as under [President David T.] McLaughlin '54. The Dartmouth Review was, it seemed to me, a reaction to the atmosphere on campus, which was much less tolerant.

Did being appointed to the Alumni Council in 1987 help shape your view of the College?

The first and only meeting I went to was right after Freedman had been made president. I urged a combined alumni-faculty committee to encourage tolerance of diverse political, religious, economic views. There was a very close vote among members of the Alumni Council, and to my astonishment Freedman was lobbying against it. It went down by a close vote. I resigned from the Alumni Council because I realized that College governance had become too political for a federal judge. If the council would not agree to a committee devoted to toleration of diverse views then I didn't belong there.

What's your sense of the state of affairs at Dartmouth rightnow, in the wake of contentious alumni elections?

I think it's much more tolerant than it was back in the 1980s. As I told [chairman of the board of trustees] Ed Haldeman '70 at a recent alumni affairs event, I do not express views on political questions, even political questions at Dartmouth.

You've said you did not feel it appropriate for a federal judge to serve on Dartmouth's board of trustees despite many friends urging you to do so, yet you did serve on the board of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA), a group accused of funding the Association of Alumni lawsuit against the College. Any comment?

I joined the board of that foundation before I became a judge. At the time my impression was that it was rigorously bipartisan. Sen. Joe Lieberman was involved. But yes, it was designed to fight political correctness. My son called me I think it was a year or two ago, in the fall. My son is rather close to Jim Wright and he went up there to have lunch with Jim and Jim complained about my being on the board of this group that had criticized him. I found out to my astonishment that ACTA had written a letter criticizing Wright for not being neutral. My son had told him, "My dad would never take a position on a political issue, being a judge." I was mystified. It was implicitly taking a position so I immediately resigned from the board. I sent a copy [of the resignation letter] to Jim.

Are there particular memories from your student days thatstand out?

The most important influences on me at Dartmouth were two professors. The late Arthur Wilson, who was in the government department and a specialist on biography, became very much my mentor. He tried very hard to convince me to go to Yale Law School instead of Harvard because he was enamored with the Yale approach, which was then and perhaps even now less focused on law and more interested in law and something else—not law without context. He was a very great professor. My son Bob was writing a paper for Wilson when he died at the end of Bob's junior year.

The second was John Adams. I found out recently that his real name was Adamovicz, which may explain why he was so interested in Serbia. He once said that the Serbs were the greatest people in Europe because they could turn the most complicated problems into the most simple formula: Nine grams in the back of the neck.

If you look at my yearbook you'll see I was a member of the Law Club, the International Relations Club and the Republican Club. That's my career in a nutshell. When I was at Dartmouth I loved it socially but I was a bit troubled by the anti-intellectual atmosphere. A good friend of mine who was playing football at Harvard at one point thought of transferring to Dartmouth. I was thinking of transferring to Harvard. We talked each other out of it, but I do love both places.

Even before law school you spent time at Harvard, though.How did that come about?

I was kicked out of Dartmouth for a semester. The charge was conduct unbecoming a Dartmouth gentleman. It was alleged that I had spent a night at a dormitory at Skidmore College. I defended it, I think, on the grounds that the charge was inconsistent on its terms. That's a joke, but I still claim there was no evidence. Or insufficient evidence! But probably correctly, evidentiary hearings weren't necessary.

The FBI later picked this up, so everyone knows it. The great irony is I gave a speech a couple years ago about the Yale Five, the Orthodox Jews who refused to live in coed dormitories. The case went up to the Second Circuit. The argument was they should be able to live in single-sex dormitories because of religious concerns. The five were backed by fundamentalist Christians, and Yale was quite distressed about that. I thought there was great irony in that. Here these kids were threatened with expulsion for not doing what I was suspended for doing 40 years before. My defense should have been I was 40 years ahead of my time.

Were you interested in law before you got to Dartmouth?

I always wanted to be a lawyer. From my earliest childhood, from the age of 6 or 7. Probably, my mother and grandmother would say, because I argued all the time. I always wanted to go to Harvard Law School. My grandfather put that idea in my head when I was only a child. He was a very successful businessman who had enormous respect for lawyers. I also had one uncle who was a lawyer who had gone to Penn.

Returning to your public service, can you reflect on your workon the Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the UnitedStates Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction?

We wanted to look at why the intelligence community had made a mistake and to recommend any changes we thought appropriate to our intelligence and counterintelligence agencies. We did make a number of recommendations, including that the FBI set up a separate service for intelligence and counterterrorism. I found that a fascinating experience.

I have always been interested in intelligence and counter intelligence. I had some experience with it as deputy attorney general and as ambassador. I was once head of the transition at CIA when Reagan was elected. I thought the subject matter was fascinating. It was also interesting to abandon the judicial role. It's legitimate for a senior judge to take an appointment in the executive branch of the government. It was not overtly political. It was bipartisan. It was interesting to shift back to a role that was more similar to what I had in the executive branch before I became a judge. I had a wonderful group of people enormously capable, some of the most distinguished minds around. We worked very hard. We wrote our own report with the aid of some brilliant young lawyers. I was rather amused that one of the senior persons on our staff, who had served on prior commissions, said he never served on a commission where the members wrote their own report.

How did the Medal of Freedom come about?

I have no idea. I was at a judicial conference when I got a call from an ex-law clerk of mine who is a deputy secretary to the president. He called me to tell me I was going to get this award. I wasn't sure whether he said I had been nominated or whether I was getting the award. He said it was very confidential. It was quite a thrill. It was a great thrill to have all eight grandchildren and three children at the ceremony as well as their spouses.

A judge should hold to the notion that there is a right answer to every case. If you believe there is a theoretical right answer to the case, you are not tempted as much into the policy realm,"

a resident Wright has dialed backpolitical correctness quite significantly. But there mras a time when Dartmouth,! in my judgment, aciiwelw discouraged free speech. I thought that was profoundly wrong."

MATTHEW MOSK covers national politics for The Washington Post A frequent contributor to DAM, he lives in Maryland.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

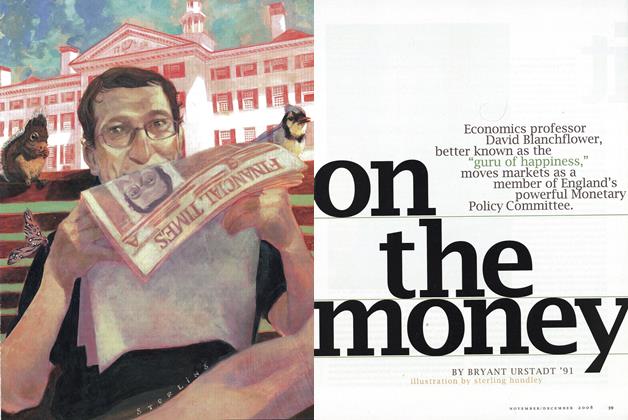

FeatureOn the Money

November | December 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

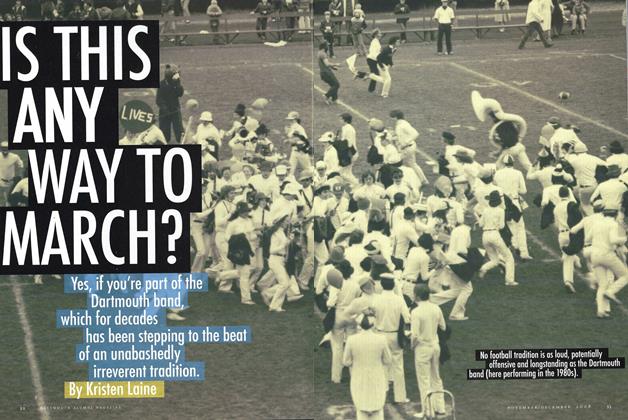

FeatureIs This Any Way To March?

November | December 2008 By Kristen Laine -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2008 By Bruce Beasley '61 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Vicious Cycle

November | December 2008 By Latria Graham ’08 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

November | December 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91

Matthew Mosk ’92

-

Feature

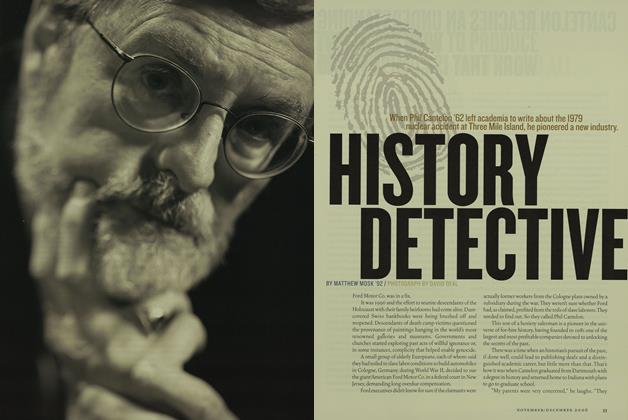

FeatureHistory Detective

Nov/Dec 2006 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

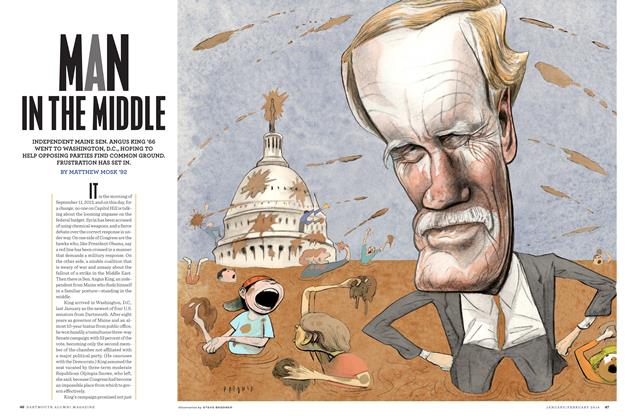

FeatureMan in the Middle

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

THE DAM INTERVIEW

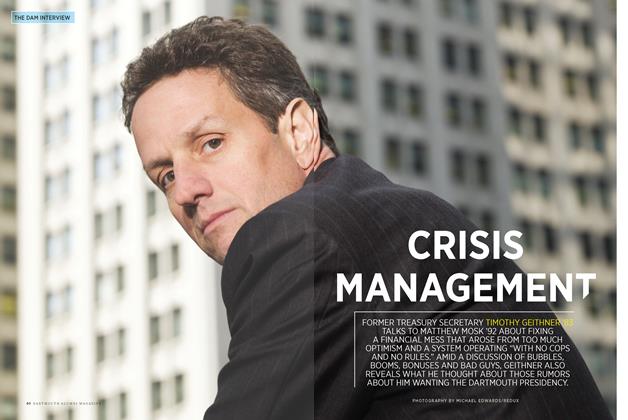

THE DAM INTERVIEWCrisis Management

July | August 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

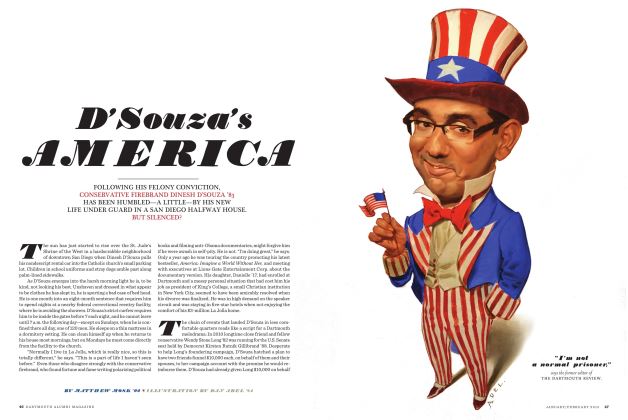

FeatureD’Souza’s America

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Fixer

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Sports

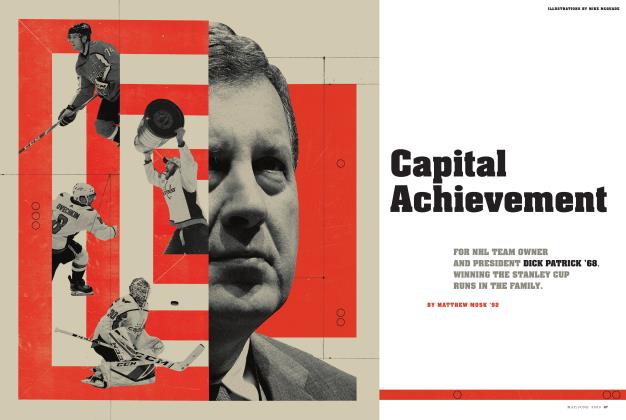

SportsCapital Achievement

MAY | JUNE 2020 By Matthew Mosk ’92