Sage on Stage

Thomas Vance was the epitome of professor as lecturer, a model now out of favor.

Mar/Apr 2008 Mike O’Connell ’65Thomas Vance was the epitome of professor as lecturer, a model now out of favor.

Mar/Apr 2008 Mike O’Connell ’65Thomas Vance was the epitome of professor as lecturer, a model now out of favor.

THE DARTMOUTH OF MY DAY HAD NO department of education. But for those men of the 1960s who would pursue a career in teaching, the campus offered a colorful spectrum of role models. Irascible Herb West (comparative literature) and droll Al Foley (history) were still powerful presences on the platform, and Young Turks Vincent Starzinger (government) and Noel Perrin (English) were becoming crowd-pleasers and voices of authority. Painstaking Elmer Smead could hold forth for an entire trimester on a single murder trial, and soft-spoken Churchill Lathrop dazzled us in an art history course we dubbed "Darkness at Noon."

But as the century drew to a close, this learning-at-the-feet-of-the-master brand of education was called into question, then stigmatized by educational reformers. The "sage on the stage" lecturer was given the hook when in 1993 University of California-San Marcos educa- tion professor Alison Kings "guide on the side" facilitator was touted as the ideal. King wrote that the time-honored college lecture format "assumes that the students mind is an empty container into which the professor pours knowledge...students are passive learners rather than active ones. Such a view is outdated and will not be effective for the 21st century, when individuals will be expected to think for themselves, pose and solve complex problems and generally produce knowledge rather than reproduce it."

Last year in a Chronicle ofHigher Education piece I drew a composite portrait of the sage on the stage as recalled from Dartmouth lectures: "He is independent, idiosyncratic, iconoclastic, profane, unimpeachable. Although he can be dogmatic and dictatorial and does not suffer fools gladly, he welcomes questions, encourages dissent and rewards independent thinking. He regards the students brain not as a vessel to be filled, but a muscle to be exercised."

After my piece appeared I received a steady stream of e-mails and letters from longtime college lecturers who say they have been harassed by reformers to fall in line with alternative learning methodologies such as small group projects and peer review sessions—the same "cutting edge" initiatives I recall from junior high school in the 19505. The dying breed of lecturers say (not for publication) that the reformers don't like lecturing because they're not up to it. One goes so far as to say the attack on lecturing is an indirect attack on reading, another learning activity in which a student learns from sustained concentration on the voice of a lone speaker.

I'm glad I went to college in the golden age of the sage. Of the many whose voices have stayed with me, the manI remember best was Thomas Vance, who died two decades ago at the age of 79.

Vance was Dartmouth's high priest of modern poetry from 1940 until his retirement in 1973. Although a favorite of English majors, he was something of a Sanborn House anachronism: an urbane, manly sophisticate among a faculty and administration well-stocked with Big Green types. You would not find him cheering a power play at a hockey game or eating green eggs and ham on the freshman trip, and Robert Frost, class of 1896, was no more likely to appear on his course syllabus than was James Whitcomb Riley.

Like my contemporaries, I took professors rather than courses. I signed up for English 74 my sophomore year based on Vance's reputation as a brilliant lecturer and literary virtuoso. (Unbeknownst to me at the time, he was a Yale man and World War II Navy officer who had taught at Princeton, the University of Virginia and the Sorbonne.) Reality outran apprehension at the first meeting of the class in crowded Carpenter Hall, where Vance—tall, wide-shouldered, majestic—strode to the platform at the stroke of the hour. As he gazed out at the unwashed masses, the arresting features of his physiognomy were his squinting, sunken eyes, blurred behind thick spectacles, no doubt damaged by the exhausting reading regimen of a man who took all knowledge for his province.

His opening lecture was a scholarly tour de force: a wide-ranging, humorous and deadly commentary on a single short poem, "Mr. Apollinax," by T.S. Eliot. By the end of the hour I knew full well that I was out of my depth in Vance's class. I also knew I wanted to be an English major.

While the extent of his learning was daunting even to his senior faculty colleagues, Vance was never aloof or condescending. He did not leave us, as he left Mr. Apollinax, pinned and wriggling on the wall. Though painfully aware of our literary deficiencies, he sought out our opinions, encouraged us in our efforts, kept track of our accomplishments and enthusiasms. Even in classes of 60 or more he was adept at calling students by name with challenging questions.

I got my head handed to me one day my sophomore year when he asked me how the imagery in the opening lines of Yeats' "Sailing to Byzantium"—"The salmon falls, the mackerel-crowded seas"—advances the theme of the poem.

I was paralyzed. Vance rephrased the question, somewhat in the manner of James Thurber's "University Days" professor trying to coax the brawny Bolenciecwczinto naming one form, any form, of transportation. But I remained mute, and Vance mercifully turned the question to an upperclassman. I was despondent, not so much for having embarrassed myself but for having disappointed the man whose teaching I had come to love. I spent my remaining eight trimesters trying to atone for that imagined disaster.

By spring term of my senior year I had redeemed myself with a passable performance in Vance's "Modern Tragedy" seminar. But I still had not had enough of the man. English 74, my old stumbling block, was meeting Saturday mornings in Sanborn's Christopher Wren Room, and I decided to drop in. Vance appeared puzzled as to why I was there, but he'had to have known. It was for the same reason everyone else was there: to see the sunlight streaming through the tall windows on the shoulders of the impossible possible philosophers' man; to gaze with him once more toward the ineluctable modality of the visible.

For all his treasure hunting for literary allusions and mythological references, Vance, more than any other teacher, made us aware of the ineffable nature of poetry, the haunting stuff that gets left out in translation. He knew the limits of analysis and deconstruction. He admired e.e. cummings for his elusiveness, his lighterthan-air ability to defy rational interpretation: "No one, not even the rain, has such small hands." I will never forget his wistful, laconic speculation on the untold emotions pulsing between the closing lines of the letter written by the abandoned child bride in Rihaku's "The River Merchants Wife:"

If you are coming through the narrowsOf the River KiangPlease let me know beforehandAnd I will come out to meet youAs far as Cho-fu-Sa.

Reading in translation and lacking a map of the territory, said Vance, we don't know just how far that is. What we did know is that the likes of Thomas Vance would not be coming down the river again any time soon.

Virtuoso Vance washigh priest of poetryat Dartmouth from1940 to 1973.

Vance, more than any other teacher, made us aware of the ineffable nature of poetry.

MIKE O'CONNELL is a part-time Englishlecturer at the University of WisconsinBarahoo and Richland campuses.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Numbers Game

March | April 2008 By LAUREN ZERANSKI ’02 -

Feature

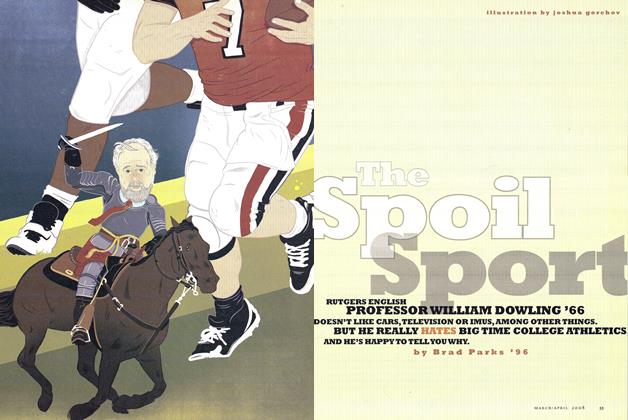

FeatureThe Spoil Sport

March | April 2008 By Brad Parks '96 -

Feature

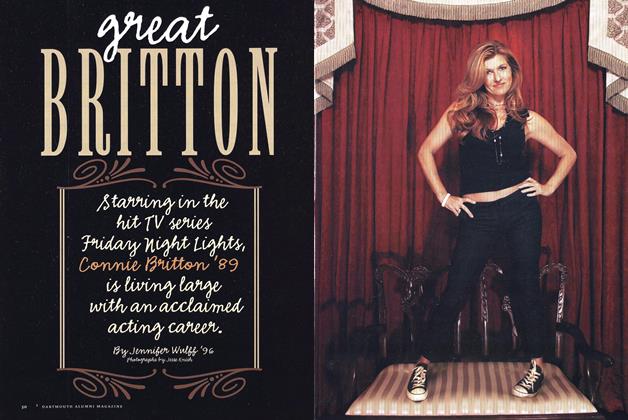

FeatureGreat Britton

March | April 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Interview

Interview“The Timing is Right”

March | April 2008 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONDesigner Genes

March | April 2008 By Ronald M. Green -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLiving Room Learning

March | April 2008 By Jane Varner Malhotra '90

Mike O’Connell ’65

TRIBUTE

-

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEStories in Stone

May/June 2005 By Andy Rowles ’65 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEHER LESSONS ECHO STILL

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By DAVID DOWNIE '88 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEA Go-To Guy

Nov/Dec 2004 By David Shribman ’76 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTERemembering Earl Jette

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELate Fall Practice

Nov/Dec 2006 By Sara E. Quay -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEThe Novelist’s Muse

Nov/Dec 2009 By Tom Maremaa ’67