Late Fall Practice

The waters of the Connecticut River continue to connect an alum’s daughter to her late rowing father.

Nov/Dec 2006 Sara E. QuayThe waters of the Connecticut River continue to connect an alum’s daughter to her late rowing father.

Nov/Dec 2006 Sara E. QuayThe waters of the Connecticut River continue to connect an alum's daughter to her late rowing father.

IN THE FALL OF 2000 MY father, William H. Quay Jr. '62, collapsed and died of a heart attack after finishing a recreational row with his friends at the Long Beach (California) Rowing Association. When I was told of his death, I was overwhelmed by feelings that accompany the loss of a parent: shock, disbelief, grief. I was also reminded of my fathers relationship with Dartmouth, primarily through a painting of the Dartmouth rowing team that was among my fathers possessions.

I remembered the painting quite suddenly in the emotional aftermath of loss. When I was a child the painting hung in our home, a dark-blue background upon which was painted the slender, golden silhouette of a rowing crew. Although I hadn't seen the painting since I was a child, I knew it was from my fathers years at Dartmouth, where he had rowed crew for four years with a passion that had endured, literally, until the day he died. I also knew, the way we know things in the hours and days after we lose someone we love, that the painting, titled Late FallPractice, was the one belonging of his I desperately wanted to find, and keep, in memory of him.

Looking back on the urgency of that desire, it makes sense to me now why a painting of the Dartmouth crew—on the Connecticut River against the backdrop of the Vermont hills—might have been so important to me upon my fathers death. After age 7, when my parents divorced, I saw my father less and less frequently. As a result our early years together were that much more potent in my memory, and those early memories were infused with two main things: Dartmouth and rowing.

Throughout my childhood I was surrounded by Dartmouth memorabilia. Stories about the Winter Carnivals and pictures of the ice sculptures were regular fare in our family history. A black, wooden Dartmouth chair and gilded mirror formed the background of numerous family photos. As a teenager I wore my father's green wool Dartmouth sweater to skating lessons, and a green-and-white striped Dartmouth scarf was in my winter clothing drawer for years. Pictures of my father on the dock of the Dartmouth boathouse were everywhere, for my fathers love of the sport had taken shape at Dartmouth. The connection between my father and the College was real to me in the mysterious and magical way that things are real in childhood. And as I grew older this connection became the way in which I tried to decipher my father, to find clues to the man who had moved across the country and who I saw only a few times throughout the year.

Dartmouth served as another connection between me and my father when I attended his 25th reunion with him. The invitation to do so came after I told him I wanted to know more about who he was. So we .made the drive from Boston to Hanover together and slept in the dorms. I watched the current Dartmouth crew race against my father and his College teammates. Those mates, especially Dave Gundy '62, Dick Briggs '62 and Dave Haist '62, provided me with another way to know my father—who was a teammate, a roommate and a lifelong friend. These relationships added much richness to my understanding of his life.

He was, as his friends helped me to know, a rower, and he spent most of the last 10 years of his life doing what he began at Dartmouth and continued throughout his life, simply because he loved it. From an international competition in Argentina to local regattas in Long Beach, my father rowed. When he suffered a first heart attack at the end of the San Diego Classic in 1998, nearly drowning when he fell from the boat into the water before his teammates knew what had happened, my father did not stop rowing, despite the risk of taxing his heart yet again. He simply decided not to row competitively and spent the next two and a half years rowing recreationally, just as he had been doing the morning he died.

The July after my father rowed for the last time, I spent a week at Dartmouth in a Spanish immersion program. I knew that to spend time in this space—which my father had loved and where so many of my memories of him are lodgedwould be bittersweet. In the week that marked the nine-month anniversary of his death, I arrived in Hanover and, as the campus shone in the afternoon light, I set out on a run through the place that was so uncannily familiar to me.

I paused somewhere down by the boathouse, as the sun was angling through the tall trees in the late afternoon light, and I thought about how this place, this water, this dock, still connected me to him. How he had stood right here, perhaps in this exact spot, and looked out at the water in anticipation of the days practice or race.

As I watched an eight-man shell skim effortlessly past on the water, I was struck by the palpable connection between my father and Dartmouth: the sense of nostalgia I felt looking at the river on which he had rowed so many times, the inevitable way life turns back on itself, and the irony inherent in the painting that I had recovered from his belongings to hang in my own home. My fathers death, on October 28,2000, was his last late fall practice.

SARA E. QUAY is the dean of education atEndicott College in Beverly,Massachusetts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

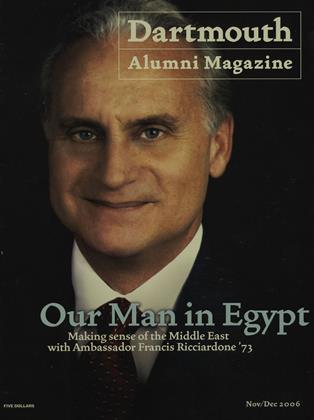

Cover Story

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

November | December 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureNot Your Mother’s Bible

November | December 2006 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’05 -

Feature

FeatureHistory Detective

November | December 2006 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONFailing the Test

November | December 2006 By John Merrow ’63 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSReturn of Pinto

November | December 2006 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Sports

SportsTips of the Trade

November | December 2006 By Courtney Banghart ’00

TRIBUTE

-

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEStories in Stone

May/June 2005 By Andy Rowles ’65 -

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May/June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEA Life Well Lived

Jan/Feb 2011 By Deborah Schupack ’84 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTENo Quieter Bed

Sept/Oct 2005 By James Zug ’91 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEChristian Existentialist

Nov/Dec 2007 By Jeffrey Hart ’51 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTERemembering Earl Jette

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By JIM COLLINS ’84