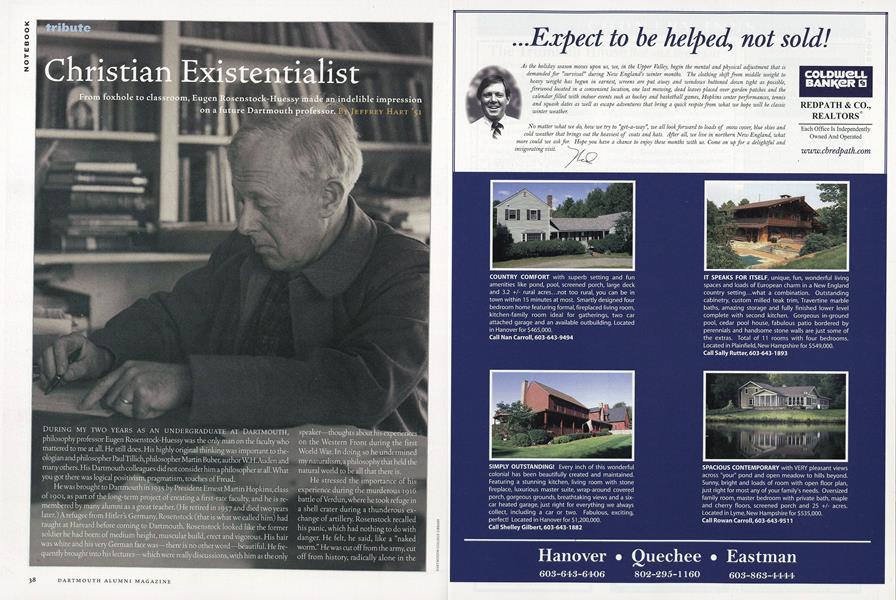

Christian Existentialist

From foxhole to classroom, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy made an indelible impression on a future Dartmouth professor.

Nov/Dec 2007 Jeffrey Hart ’51From foxhole to classroom, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy made an indelible impression on a future Dartmouth professor.

Nov/Dec 2007 Jeffrey Hart ’51From foxhole to classroom, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy made an indelible impression on a future Dartmouth professor.

DURING MY TWO YEARS AS AN UNDERGRADUATE AT, DARTMOUTH, philosophy professor Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy was the only man on the faculty who mattered to me at all. He still does. His highly original thinking was important to the ologian and philosopher Paul Tillich, philosopher Martin Buber, author W.H.Auden and: many others. His Dartmouth colleagues did not considerhim a philosopher at all.What you got there was logical positivism, pragmatism,touches of Freud.

He was brought to Dartmouth in 1935 by President Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, as part of the long-term project of creating a first-rate faculty, and he is re membered by many alumni as a great teacher. (He retired in 1957 and died two years later,A refugee from Hitler's Germany, Rosenstock (that is what we called him) had taught at Harvard before coming to Dartmouth. Rosenstock looked like the former he lad been: of medium height, musculajr build, erect and vigorous. His hair was white and his very German face was—there is no other word—beautiful. He frequently brought in to his speaker—thoughts about his on the Western Frort during the first; World War. In doing so he undermined my naturalism, a philosophy that held the natural world to be all that there is.

He stressed the importance of his experience during the murderous 1916 battle of Verdun, where he took refuge in a shell crater during a thunderous exchange of artillery. Rosenstock recalled his panic, which had nothing to do with danger. He felt, he said, like a "naked worm." He was cut off from the army, cut off from history; radically alone in the universe. Meaningless.

German philosopher Karl Jaspers once defined existentialism as philosophizing "where you stand." Where Rosenstock stood, or lay, was in that foxhole out in no man's land between the lines at Verdun. From that nadir, meaning had to be created—or re-created.

"History must be told," he said repeatedly. History is to civilization what memory is to an individual: the source of identity, the constituting of a soul.

Often Rosenstock began a class by citing some item from the day's news. Or from history, American history or the history of Dartmouth College. "Gentlemen," he would say in his German accent, "Gentlemen, Dartmouth College in 1847 was not Dartmouth College in 1900, and neither of those was Dartmouth College in 1947. Many acts of creativity went into the recreatioru of the College, the College, gentlemen, of which you are a part today. And you, gentlemen, are part of the creation of the Dartmouth of tomorrow." Thus he reminded us that naturalism and empiricism are in the past tense.

He sometimes quoted Robert Frost's poem "The Road Not Taken." Of the poems narrator, he said, "That man, gentlemen, does not know the result of the choice he must make. He cannot check on the result that hasn't yet happened. Our choices project us forward in our own histories. We make judgments, we may be prudent, but we act on faith. We create actualities that did not exist before."

Rosenstock citing Frost, class of 1896, was particularly effective, because about 50 yards to the north of where we sat in a classroom on the second floor of Dartmouth Hall was Went worth Hall, where Frost had lived during his abbreviated freshman year, and the thought of the poet reminded us of what that man, once a freshman like us, had created.

Nietzsche was important to Rosenstock, and in more than one way. By 1947, certainly 1948, the tensions with the Soviet Union were approaching crisis intensity. Rosenstock saw Nietzsche as a prophet we could oppose to Marx. Both had foreseen our epoch of revolutions and upheavals. "If Marx had been the only prophet," Rosenstock said, "then Communism might well triumph. But Nietzsche also saw what was coming. And so we do not need to become Communists." Rosenstock's idea of prophecy was not guesswork, but the result of an intellect and imagination that enabled prophets such as Marx and Nietzsche to understand the total experience of an epoch at its beginning. He also saw Nietzsche as the prophet of individual creation as contrasted with Marxist collectivism, the superior individual as the result of heroic imagination.

We had two texts for this course, both by Rosenstock, The Multiformity of Man (1.936) and The Christian Future: Or, TheModem MindOutrun (1946). Rosenstock-Huessy was part Jewish and had become a Christian as a young man. This was regarded as apostasy, as I learned from a professor of religion who was also a rabbi. Yet the nature and basis of Rosenstock's Christianity is not easy to pin down. He does affirm, however, his belief that the Resurrection did actually happen, in a paragraph that appears in a section of The Christian Future: "Perhaps a personal confession is permissible here. I had always hoped to be a Christian. But 20 years ago I felt that I was undergoing a real crucifixion. I was deprived of all my powers, virtually paralyzed, yet I came to life again, a changed man. What saved me was that I could look back to the supreme of Jesus' life and recognize my small eclipse in his great suffering. That enabled me to wait in complete faith for resurrection to follow crucifixion in my own experience. Ever since then it has seemed foolish to doubt the historical reality of the original Crucifixion and Resurrection."

Never in class did anyone challenge the non sequitur that links the final sentence of that paragraph to the sentences that precede it. This probably was because that paragraph was swallowed up in and forgotten due to what seemed far more central to Rosenstocks teaching: the activity of the martyrs, including Jesus, in our living speech and in history. For Rosenstock, God was not an object of speculation, not a metaphysical reality, but a "You" addressed by an "I" who is changed by this act of speech.

Rosenstock crystallized his thought in aphorisms, many collected by George Morgan in his Speech and Society: TheChristian Linguistic Social Philosophy ofEugen Rosenstock-Huessy. Among them: "Every value in human history is first set on high by one single event which lends its name and gives meaning to later events. We have seen many movements called 'crusades,' but they derive their name, if it is properly given, from the first Crusade. Crucifixion and Resurrection would not be known as everyday occurrences in our lives if they had not happened once for all."

Rosenstock regarded the Old Testament as the period of God the Father, the period Anno Domini following as that of God the Son, and our present era as that of God as Holy Spirit, the final unification of humanity, the Many becoming One. That oneness seemed much less likely in 1947 and 1948 than it does now, as the world is becoming interdependent economically as well as in communications and intercontinental travel. Part of Rosenstock's power in class was his erudition, deployed in historical sweeps, part in the sense of mystery that inhered in his sometimes oracular utterances. There were many more things in heaven and earth than were dreamed of in my sophomore naturalism.

For Rosenstock, God was notan object of speculation,not a metaphysical reality.

JEFFREY HART, professor emeritus of English,is helping to make Rosenstock-Huessy'sbooks and papers available to scholars by arrangingthem in the College archives.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

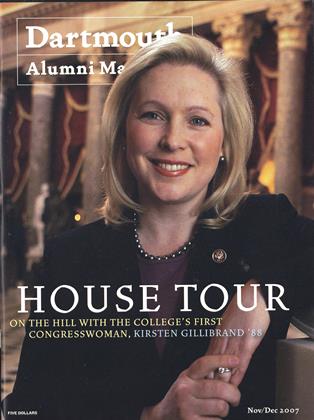

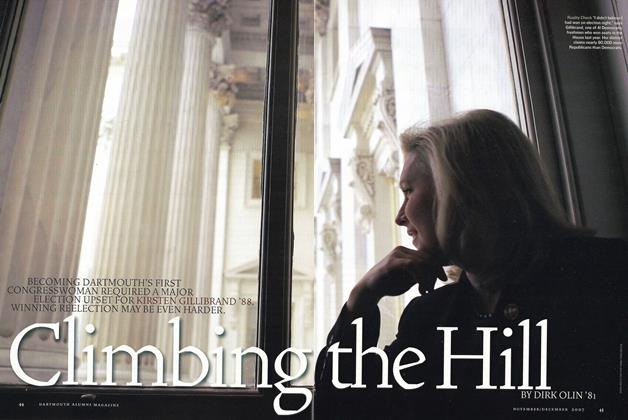

Cover Story

Cover StoryClimbing the Hill

November | December 2007 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

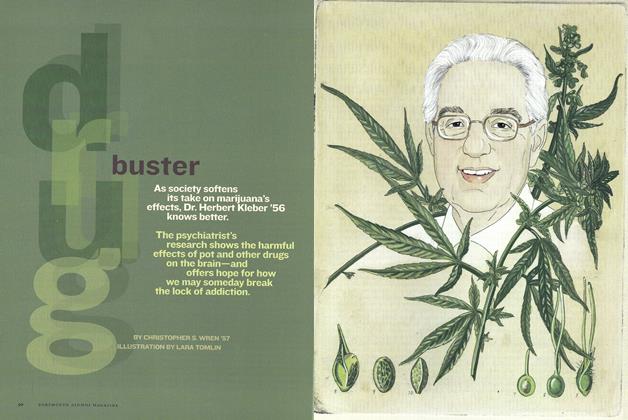

Feature

FeatureDrug Buster

November | December 2007 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

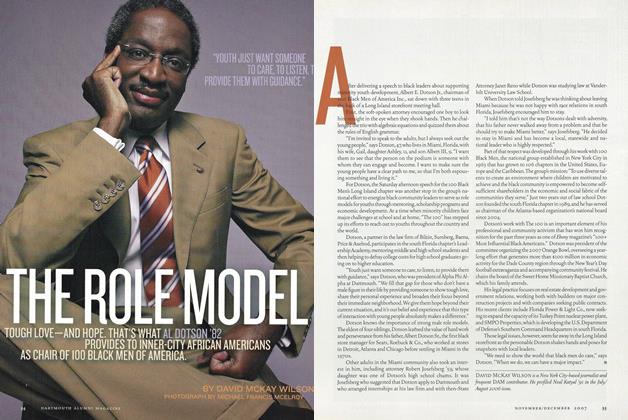

FeatureThe Role Model

November | December 2007 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2007 By Kristin Brenneman '97 -

ONLINE

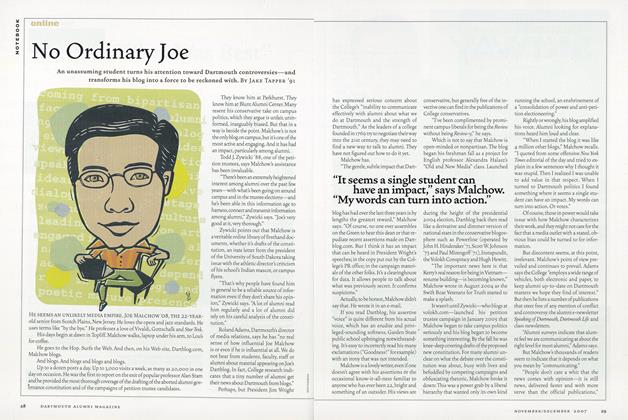

ONLINENo Ordinary Joe

November | December 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91

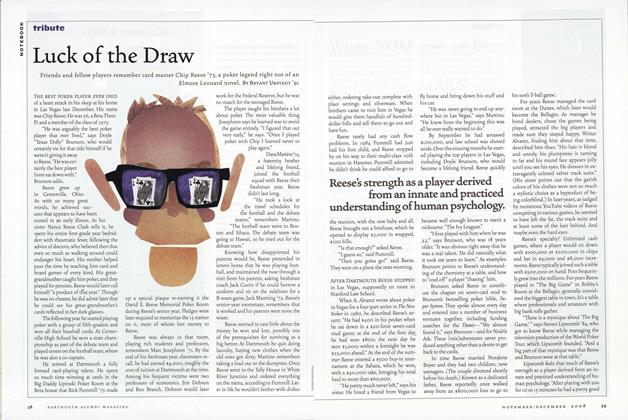

TRIBUTE

-

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

Nov/Dec 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEHer Lessons Echo Still

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By DAVID DOWNIE '88 -

TRIBUTE

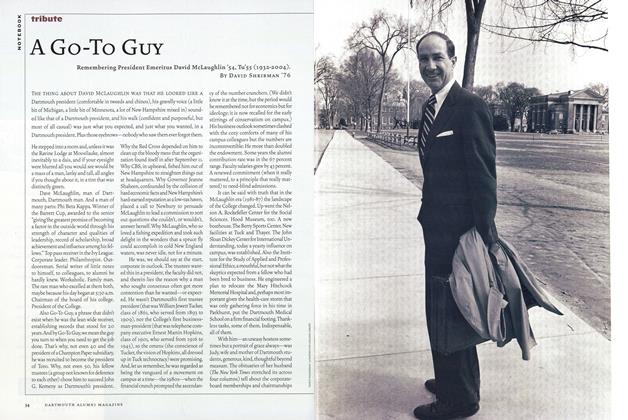

TRIBUTEA Go-To Guy

Nov/Dec 2004 By David Shribman ’76 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTE“Why Blue?”

July/August 2011 By James D. Fernández ’83 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTENo Quieter Bed

Sept/Oct 2005 By James Zug ’91 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTESage on Stage

Mar/Apr 2008 By Mike O’Connell ’65