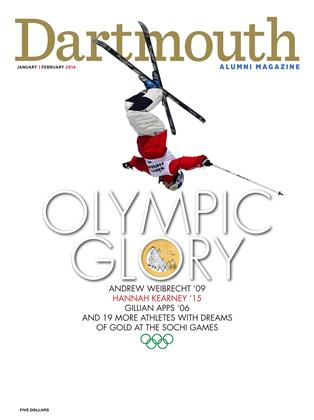

He’s called “Warhorse,” but the downhiller and 2010 bronze medalist is really just a speed freak.

When an overnight snowstorm canceled the men’s downhill training runs at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, Andrew “Warhorse” Weibrecht and some of his American teammates went up higher onto Whistler Mountain to get in a few hours of powder skiing, just for the fun of it—something none of the single-focus European racers would have dreamed of doing. The next day Weibrecht finished 21st in the downhill. New Yorker writer Nick Paumgarten asked him if he planned to do any more free-skiing that week. “Naw,” Weibrecht told him. “My legs are cashed. I overdid it yesterday.”

That an Olympic athlete would go out and exhaust himself having fun just before the biggest race of his career wouldn’t surprise the skiers who came to know Weibrecht at Dartmouth. Nor would it surprise them that, four days later, on a flawless sunlit day, Weibrecht absolutely hurled himself down the hard-ice course in the Super-G competition, the hybrid event that grafts the speed of downhill onto the technical turning skills of slalom. Coming through the 180-degree turn through the heart-stopping, 58-degree slope called “the Fallaway,” Weibrecht caught an edge and nearly caught a gate. He skirted disaster at better than 80 m.p.h., almost losing control twice in the first 60 seconds. The run reminded observers of the stunning edge-of-mayhem World Cup run he made in a snowstorm at Beaver Creek in 2007, when he surged from 53rd to 10th and became a YouTube sensation.

The Whistler race was shaping up as pure Warhorse—a 5-foot, 6-inch, 190-pound cannonball shot of all-or-nothing speed. He held his line— always the fastest, most dangerous line—through the twisting curves into “Boyd’s Chin,” finished off turns 32 and 33 through the final technical section of “Murr’s Jump” and tucked it across the finish line at 1:30.65. He braked hard to stop and pumped his fist skyward, grinning wide. He had been the third, and fastest, racer down the course.

Next he waited and watched while 17 other racers flamed out or skied off course and 42 others flew across the finish line. In the unforgiving world of alpine ski racing, only two of those racers skied the course faster: The Norwegian champion Aksel Lund Svindal, at 1:30.34, and the greatest American alpine skier of all time, Bode Miller, at 1:30.62—just three one-hundredths of a second faster than the bronze-winning Weibrecht. The unexpected result put the unheralded Dartmouth student in fast company with Miller and women’s downhiller Lindsey Vonn on that week’s cover of Sports Illustrated.

It was Vonn’s former husband, downhiller Thomas Vonn—along with teammate Dane Spencer—who gave Weibrecht the name “Warhorse” when he was a rookie with the U.S. Ski Team. The nickname captured the way the new skier attacked the mountain. It stuck.

Almost four years after winning the bronze in Vancouver, following World Cup seasons interrupted by two shoulder surgeries and two ankle surgeries, Warhorse has earned the other definitions of the name: He’s still a charger, but he’s also become a veteran who has endured many struggles and battles.

He’s worked hard to get his strength and fitness back into top form. He’s finally feeling good again. He’s psyched about his new skis made by Head. It’s the first season in 25 years that he’s has raced on anything other than Rossignol. “By Sochi I should have the skis dialed in,” he says from his home in Lake Placid, New York, on a short break between the team’s speed camp in Portillo, Chile, and the final training camp about to start up in Colorado.

Like many top young racers, Weibrecht applied to Dartmouth just as he was starting out on the U.S. ski circuit. As his career progressed he made the decision to stay with the U.S. program and take advantage of Dartmouth’s unique quarter system to pick away at a degree one term at a time. There was some irony in his decision. During a fall term when he was still new to the U.S. Ski Team, long before Vancouver, Weibrecht was questioning whether he still had the fire to continue racing. Doing dry-land training with the Dartmouth skiers (“and just being in that atmosphere,” he says), he felt his passion reignite. Without Dartmouth there would have been no bronze medal.

“About half of the World Cup skiers connected to Dartmouth are like Andrew,” says Chip Knight, Dartmouth’s director of skiing, “especially in the men’s downhill. Many of the best skiers in the country apply here and then defer to see how their careers unfold. After a year or two a lot of them end up falling back on Dartmouth and skiing for us.” The other half typically enter Dartmouth as strong Winter Carnival-level skiers, get faster each year and make the World Cup team after graduating.

Graduating for Weibrecht will have to wait. At 27, he has three terms left to finish his degree but is running out of earth sciences classes to take during the one time of year—spring term—when he can devote himself to his studies. He admits to feeling increasingly old and “a little awkward” when he’s back on campus (though a more focused student). In September 2010 he married Denja Rand, and he is beginning to think he’ll likely finish off the remaining terms consecutively when his racing career is over.

That could be a while. The veteran is still young enough to have a lot of races left in him, perhaps even a third Olympics in 2018—but nothing, he says, left to prove. “The bronze medal gave my career legitimacy. Winning races depends on so much: speed, conditions, luck. There have been so many great racers who never had that result, and it’s something no one can take away from me.” The defending medalist isn’t concerned that he won’t be among the favorites in Sochi. “I’m only worried,” he says, getting to the pure heart of it, “about going fast.”

"THE COOL THING ABOUT GROWING UP IN LAKE PLACID WAS SKIING ON A MOUNTAIN THAT IS PRETTY EXTREME. I DEFINITELY LEARNED TO SKI THE GNARLY BEFORE EVERYTHING ELSE." ANDREW WEIBRECHT

JIM COLLINS divides his time between Seattle and Orange, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

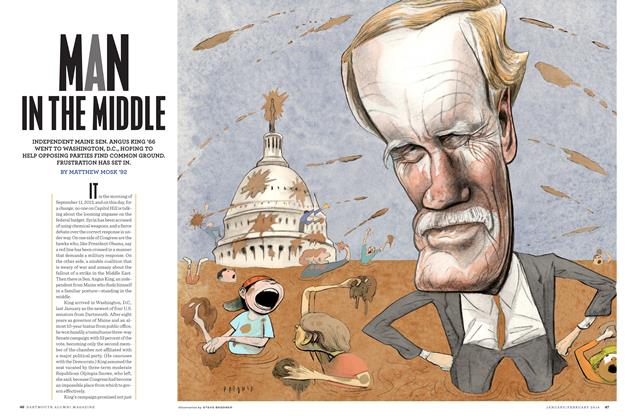

FeatureMan in the Middle

January | February 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Cover Story

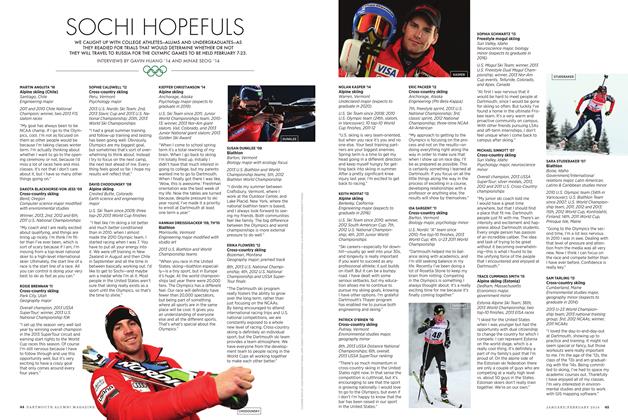

Cover StorySOCHI HOPEFULS

January | February 2014 By Gavin Huang '14, Minae Seog '14 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYThe Contenders

January | February 2014 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

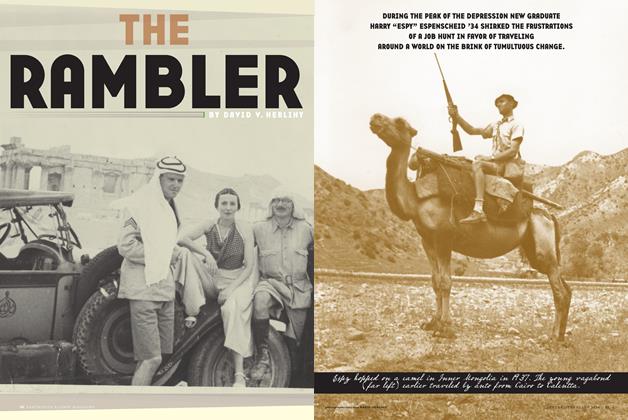

FeatureThe Rambler

January | February 2014 By DAVID V. HERLIHY -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGILLIAN APPS '06

January | February 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEHow the West Was Fun

January | February 2014 By ALEXIS C. JOLLY ’05

JIM COLLINS '84

-

Feature

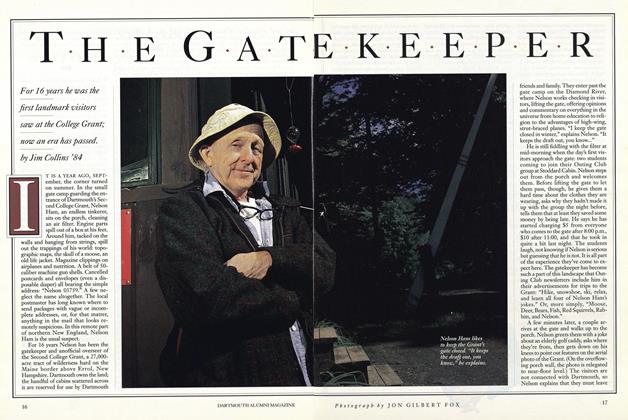

FeatureThe Gate keeper

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleLandscapes of Murder

APRIL 1997 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

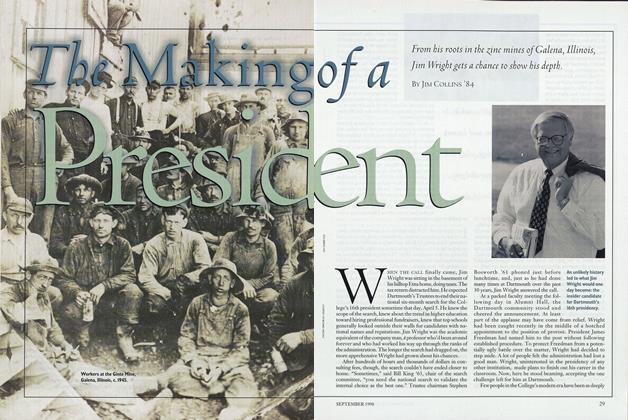

Cover StoryThe Making of a President

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

PURSUITS

PURSUITSArt of Glass

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By Jim Collins '84 -

FEATURES

FEATURESA Monk’s Journey

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By JIM COLLINS '84