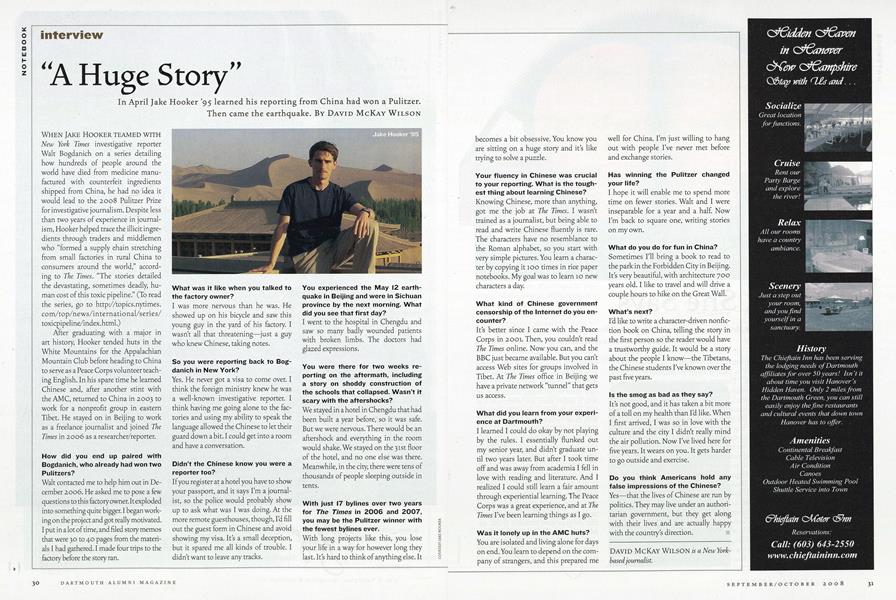

“A Huge Story”

In April Jake Hooker ’95 learned his reporting from China had won a Pulitzer. Then came the earthquake.

Sept/Oct 2008 DAVID MCKAY WILSONIn April Jake Hooker ’95 learned his reporting from China had won a Pulitzer. Then came the earthquake.

Sept/Oct 2008 DAVID MCKAY WILSONIn April Jake Hooker '95 learned his reporting from China had won a Pulitzer. Then came the earthquake.

WHEN JAKE HOOKER TEAMED WITH New York Times investigative reporter Walt Bogdanich on a series detailing how hundreds of people around the world have died from medicine manufactured with counterfeit ingredients shipped from China, he had no idea it would lead to the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for investigative journalism. Despite less than two years of experience in journalism, Hooker helped trace the illicit ingredients through traders and middlemen who "formed a supply chain stretching from small factories in rural China to consumers around the world," according to The Times. "The stories detailed the devastating, sometimes deadly, human cost of this toxic pipeline." (To read the series, go to http://topics.nytimes. com/top/news/international/series/ toxicpipeline/index.html.)

After graduating with a major in art history, Hooker tended huts in the White Mountains for the Appalachian Mountain Club before heading to China to serve as a Peace Corps volunteer teaching English. In his spare time he learned Chinese and, after another stint with the AMC, returned to China in 2003 to work for a nonprofit group in eastern Tibet. He stayed on in Beijing to work as a freelance journalist and joined TheTimes in 2006 as a researcher/reporter.

How did you end up paired withBogdanich, who already had won twoPulitzers?

Walt contacted me to help him out in December 2006. He asked me to pose a few questions to this factory owner. It exploded into something quite bigger. I began working on the project and got really motivated. I put in a lot of time, and filed story memos that were 30 to 40 pages from the materials I had gathered. I made four trips to the factory before the story ran.

What was it like when you talked tothe factory owner?

I was more nervous than he was. He showed up on his bicycle and saw this young guy in the yard of his factory. I wasn't all that threatening—just a guy who knew Chinese, taking notes.

So you were reporting back to Bogdanich in New York?

Yes. He never got a visa to come over. I think the foreign ministry knew he was a well-known investigative reporter. I think having me going alone to the factories and using my ability to speak the language allowed the Chinese to let their guard down a bit. I could get into a room and have a conversation.

Didn't the Chinese know you were areporter too?

If you register at a hotel you have to show your passport, and it says I'm a journalist, so the police would probably show up to ask what was I was doing. At the more remote guesthouses, though, I'd fill out the guest form in Chinese and avoid showing my visa. It's a small deception, but it spared me all kinds of trouble. I didn't want to leave any tracks.

You experienced the May 12 earthquake in Beijing and were in Sichuan province by the next morning. What did you see that first day?

I went to the hospital in Chengdu and saw so many badly wounded patients with broken limbs. The doctors had glazed expressions.

You were there for two weeks reporting on the aftermath, includinga story on shoddy construction ofthe schools that collapsed. Wasn't itscary with the aftershocks?

We stayed in a hotel in Chengdu that had been built a year before, so it was safe. But we were nervous. There would be an aftershock and everything in the room would shake. We stayed on the 31st floor of the hotel, and no one else was there. Meanwhile, in the city, there were tens of thousands of people sleeping outside in tents.

With just 17 bylines over two yearsfor The Times in 2006 and 2007,you may be the Pulitzer winner withthe fewest bylines ever.

With long projects like this, you lose your life in a way for however long they last. It's hard to think of anything else. It becomes a bit obsessive. You know you are sitting on a huge story and it's like trying to solve a puzzle.

Your fluency in Chinese was crucialto your reporting. What is the toughest thing about learning Chinese?

Knowing Chinese, more than anything, got me the job at The Times. I wasn't trained as a journalist, but being able to read and write Chinese fluently is rare. The characters have no resemblance to the Roman alphabet, so you start with very simple pictures. You learn a character by copying it 100 times in rice paper notebooks. My goal was to learn 10 new characters a day.

What kind of Chinese governmentcensorship of the Internet do you encounter?

It's better since I came with the Peace Corps in 2001. Then, you couldn't read The Times online. Now you can, and the BBC just became available. But you can't access Web sites for groups involved in Tibet. At The Times office in Beijing we have a private network "tunnel" that gets us access.

What did you learn from your experience at Dartmouth?

I learned I could do okay by not playing by the rules. I essentially flunked out my senior year, and didn't graduate until two years later. But after I took time off and was away from academia I fell in love with reading and literature. And I realized I could still learn a fair amount through experiential learning. The Peace Corps was a great experience, and at TheTimes I've been learning things as I go.

Was it lonely up in the AMC huts?

You are isolated and living alone for days on end. You learn to depend on the company of strangers, and this prepared me well for China. I'm just willing to hang out with people I've never met before and exchange stories.

Has winning the Pulitzer changed your life?

I hope it will enable me to spend more time on fewer stories. Walt and I were inseparable for a year and a half. Now I'm back to square one, writing stories on my own.

What do you do for fun in China?

Sometimes I'll bring a book to read to the park in the Forbidden City in Beijing. It's very beautiful, with architecture 700 years old. I like to travel and will drive a couple hours to hike on the Great Wall.

What's next?

I'd like to write a character-driven nonfiction book on China, telling the story in the first person so the reader would have a trustworthy guide. It would be a story about the people I know—the Tibetans, the Chinese students I've known over the past five years.

Is the smog as bad as they say?

It's not good, and it has taken a bit more of a toll on my health than I'd like. When I first arrived, I was so in love with the culture and the city I didn't really mind the air pollution. Now I've lived here for five years. It wears on you. It gets harder to go outside and exercise.

Do you think Americans hold anyfalse impressions of the Chinese?

Yes—that the lives of Chinese are run by politics. They may live under an authoritarian government, but they get along with their lives and are actually happy with the country's direction.

DAVID MCKAY WILSON is a New York based journalist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

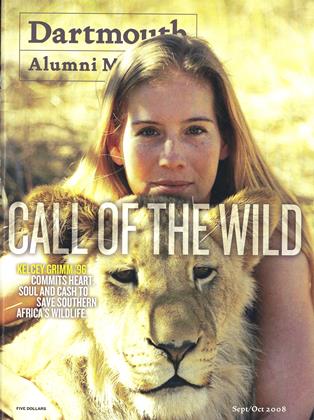

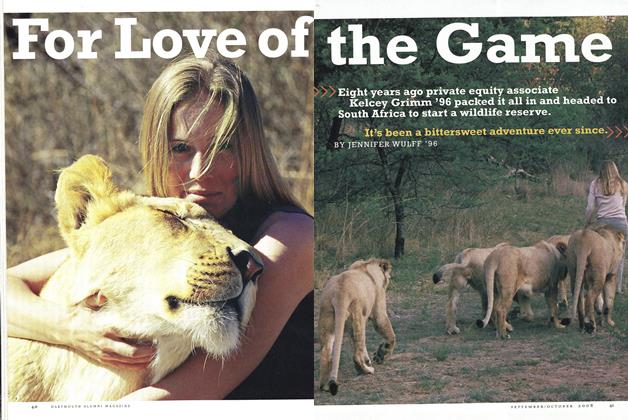

COVER STORY

COVER STORYFor Love of the Game

September | October 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

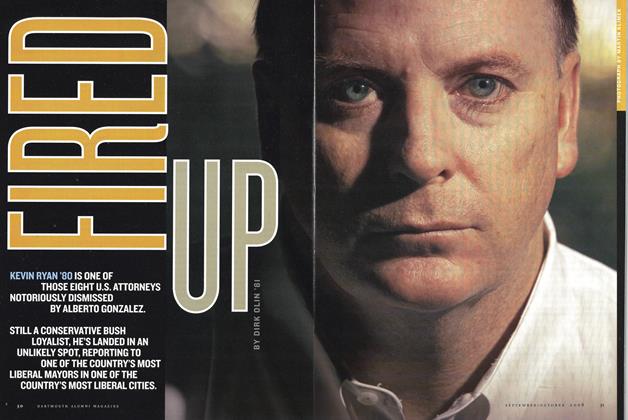

Feature

FeatureFired Up

September | October 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

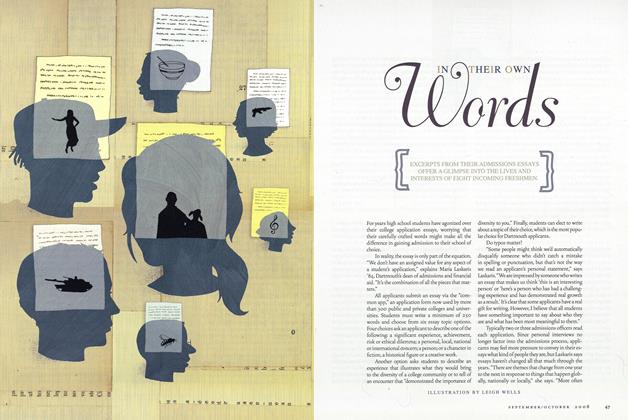

FeatureIn Their Own Words

September | October 2008 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2008 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2008 By Kristen STromber '94 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2008 By BONNIE BARBER

DAVID MCKAY WILSON

-

Feature

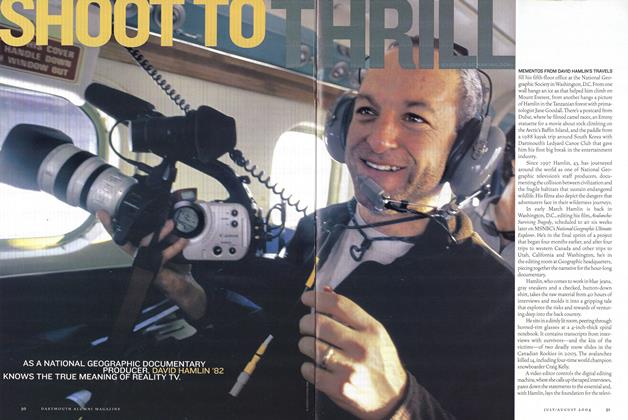

FeatureShoot to Thrill

Jul/Aug 2004 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

Sept/Oct 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July/August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Article

ArticleClass Of 1995

July/August 2007 By David McKay Wilson -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDESea Change

Jan/Feb 2009 By David McKay Wilson -

SCIENCE

SCIENCEKing Bee

Nov/Dec 2011 By David McKay Wilson

Interviews

-

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“Take the Right Risks”

MAY | JUNE 2018 By BETSY VERECKEY -

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWPhil Hanlon ’77

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2016 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEWAnnette Gordon-Reed ’81

MAY | JUNE 2016 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWState of the Union

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

May/June 2007 By Lee Michaelides -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEWFrom Advocate to Enforcer

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2025 By Matthew Mosk ’92