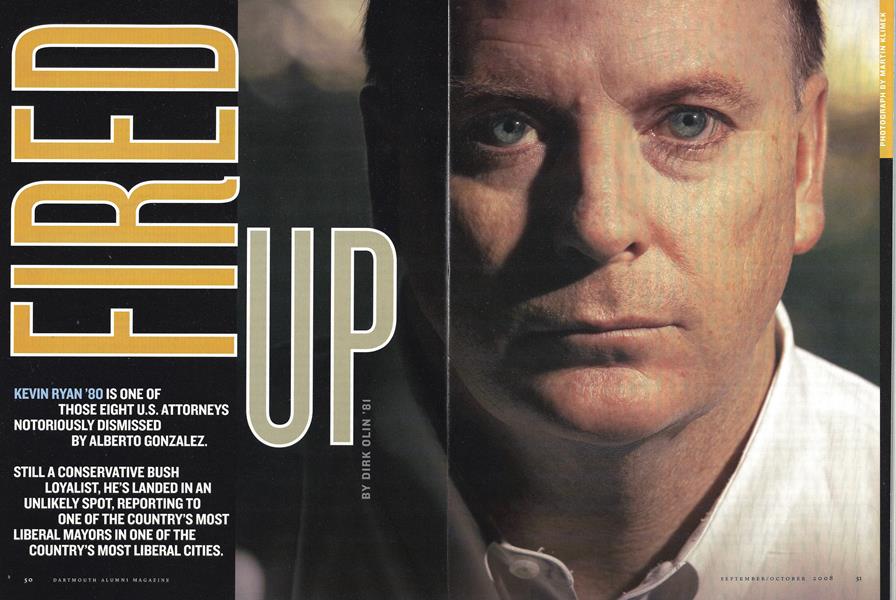

Fired Up

Kevin Ryan ’80 is one of those eight U.S. attorneys notoriously dismissed by Alberto Gonzalez.

Sept/Oct 2008 DIRK OLIN ’81Kevin Ryan ’80 is one of those eight U.S. attorneys notoriously dismissed by Alberto Gonzalez.

Sept/Oct 2008 DIRK OLIN ’81KEVIN RYAN '80 IS ONE OFTHOSE EIGHT U.S. ATTORNEYSNOTORIOUSLY DISMISSEDBY ALBERTO GONZALEZ.

STILL A CONSERVATIVE BUSHLOYALIST, HE'S LANDED IN ANUNLIKELY SPOT, REPORTING TOONE OF THE COUNTRY'S MOSTLIBERAL MAYORS IN ONE OF THECOUNTRY'S MOST LIBERAL CITIES.

family would be forgiven if they considered him a glutton for punishment. He wouldn't disagree with them. "I don't know why I was drawn back," Ryan says when asked about trading his high-rise office overlooking San Francisco for a government cubbyhole. "And I'll be honest with you—my wife didn't want me to go back to this. But this is where I live and what I do. This is what I'm best at." KEVIN RYAN'S

"This" is crime busting—first as local prosecutor, judge and U.S. attorney, now as chief of San Francisco's Office of Criminal Justice, where Ryan is the mayors point person on crime, working with the district attorney, local police and public defenders to create crime-fighting strategies. His real power? Everyone knows he has the mayors ear.

Ryan is sitting in his office, just off one of the Beaux Arts corridors of City Hall. Although the ceiling soars high above, the room's footprint matches that of a walk-in closet. A vintage porcelain sink is squeezed into a narrow recess behind his desk. Three or four picture hooks cast empty stares from otherwise barren walls.

However cramped the digs, it is somewhat appropriate that Ryan, as a former judge, should occupy a space that had been converted from judicial chambers. Harder to explain is how this conservative Republican has come to be sitting here at all. A stalwart defender of the Bush administration, for which he served as federal prosecutor, and an aggressive public apologist for such controversial instruments as the Patriot Act, Ryan is now reporting to one of the country's most liberal mayors in one of the country's most liberal cities.

"I had not been signaling to anyone that I was interested in getting back in the game," he says with a shrug. "But they came to me, and said they wanted me to do this, regardless of all the b.s. that had occurred. That meant a lot to me."

Less than a year earlier Ryan would have been found running the U.S. attorneys office for northern California, overseeing a bevy of white-hot challenges. There was immigration enforcement (considered draconian by the local left), application of the Patriot Act (considered fascist by the same Bay Area cohort) and, most famously, there was Ryan's leadership of the federal investigation into steroids in professional sports (considered far worse than his other apostasies by San Franciscans of all ideological persuasions who have spent more than a decade genuflecting at the First Church of Barry Bonds' Perpetual Cellular Resurrection). Beyond cracking down on illegal aliens and spearheading the baseball doping probe, Ryan faced all of the other heady issues inherent to a prosecutor's office with authority for federal investigations stretching from Monterey through Silicon Valley and the Bay Area all the way up to the Oregon border.

So what brought him to a municipal post for which he concedes he is "overqualified?"

The short answer is that he was one of the eight federal prosecutors whom the U.S. Department of Justice notoriously fired at the beginning of 2007. The long answer is, well, long.

"I can't go into it," he says, citing the ongoing investigations into those responsible for the dismissals. "I am not talking to anyone about that. But it is, to say the least, complicated." Was the department second-guessing his investigations? Pause. "It's complicated."

At the heart of the matter, it would be difficult to underestimate the antipathy to Ryan's chin-jutting agenda when he was federal prosecutor. This is, after all, a part of the world where George Bush is less popular than dysentery. Nor was the opposition limited to the city's theatrical street protesters. Key members of the Bay Area elite (including, crucially, those occupying the federal bench) are card-carrying members of the Unreconstructed Left. Many reportedly sought Ryan's ouster for years.

His tenure as U.S. attorney was marked by a variety of initiatives—including probes into Silicon Valley stock option back- dating and scams involving high-tech trade secrets. More unusual was Ryan's application of federal racketeering and gun law statutes to aid local law enforcement officials in cracking down on violent "career criminals." This also caused friction with federal judges, who complained their dockets were being clogged by municipal matters. But what he calls the "case of a lifetime" involved his direction of the investigation into an alleged conspiracy to distribute illegal steroids to professional athletes.

That probe carried its own costs. Leaks, eventually traced to defense counsel, were attributed to his office. Media reports critiqued, ad nauseam, his tactical decisions on who and when and how to indict. Eventually he even gave up his Giants tickets due to fan animosity. "I still haven't been back to the park," he says.

Interpersonal problems also arose, particularly after his first year—2002—when he brought in a new deputy who reportedly put distance between the offices rank-and-file and the boss. More than half of the offices 100-plus line prosecutors—disgruntled by Ryan's administrative technique, zealous agenda or both—began streaming out the door. Some say the number leaving was only slightly higher than the typical attrition rate, but the legal press published e-mails and letters leaked from office veterans bemoaning an "aloof" boss who some complained was inclined to treat tactical questions from subordinates as "disloyalty."

Push came to shove when one of the famously liberal federal judges reportedly demanded to see the internal evaluations of Ryan's performance that had been sent to Washington. By most accounts, the administrations desire to preserve the confidentiality of such documents trumped its fealty to the foot soldier. Of the U.S. attorneys sacked at the beginning of 2007, Ryan was the only one whose dismissal was not fodder for Senate Democrats claiming partisan skullduggery. They were happy to see him go.

His landing, however, augured well for Ryan's bank account. He soon set up shop at the law firm of Allen Matkins Leck Gamble Mallory & Natsis, where he began laying the foundation for what promised to be an insanely remunerative law practice defending leagues, teams or athletes caught up in the swelling maelstrom of sports-doping litigation. But something didn't feel right. "I don't know a lot of people who are ecstatic in private practice," he says philosophically, gazing at the floor with his elbows on his knees, "but I knew it wasn't for me, at least not then." He looks up, his eyes widening. "I've been a public servant for most of my adult life."

The son of first-generation Irish immigrants, Ryan was born in Edmonton in Alberta, Canada, but the family moved to San Francisco during his infancy and he became a naturalized citizen. He was raised "out in the Sunset," the district west of Twin Peaks that stretches to the Pacific. The environs were largely working class, Catholic and skewed more conservative than the rest of the city. He played football at Saint Ignatius College Prep and was among a number of late 1970s recruits brought to Hanover from "S.I." It wasn't an easy transition.

"This was a big life change—just the distance alone," he says. "All my friends were back here, because San Francisco is a parochial place. Then you add in the weather. I remember that my cleats weren't biting in the fall because the tundra was frozen solid. It was all strange to me. But over freshman year the infrastructure of the football team gave me a community."

By spring of his freshman year he'd rushed Beta and cemented friendships. And, of course, the hill winds had begun to leave the veins long about May, nudging Hanover's climate closer to San Francisco's for a while: "So I'd gotten over the weather and gotten used to a bunch of the better-off kids who had come out of boarding schools."

He and a scrum of friends switched from football to rugby for his last two years. He finished with a major in history "and practically a minor in religion," which was appropriate for a kid who had logged as many hours as Ryan had at Aquinas House. Although not involved in organized politics while at college, Ryan says his history studies and issues of the day, "from apartheid to Native American issues," began to heighten his political consciousness. "I put the rest of it all at the feet of Ronald Reagan," he says, "with his blue collar, Irish Catholic outreach. My father was a Republican, my mother was a Kennedy Democrat. And now I came into my own politics."

After college he returned home to attend law school at the University of San Francisco. "It was an immigrant thing," he says. "My father said, 'You've got to get your shingle.' So that's what I did."

While getting his J.D. he met his future wife, Anne Klingbeil, who was a friend of one of his law school classmates. (It's another sign of Ryan's historical sensitivities that he immediately launched into her family's history as "first-generation Slovenian dairy farmers in Ohio.")

He considered becoming a cop. But a quick, and more cerebral, ascent followed. He served as a prosecutor in Oakland (where he was known for occasionally joining the police on raids). Then he was tapped to serve as a Superior Court judge in San Francisco. That, too, was not a risk-free proposition. One case involving a murdered sailor attracted a stalker and threats of serious violence. "My kids were still young," he recalls. "It makes you feel different about things when the police tell you to start taking different routes to work every day."

Despite his lack of experience in the federal bureaucracy, he caught the eye of former U.S. Attorney Joseph Russoniello, who helped arrange Ryan's ill-fated appointment to the prosecutors post in 2002.

Ryan might be a bit thicker around the neck and shoulders than during his playing days. (Only a few weeks into his city post he was lamenting that he hadn't been able to make it to the gym for almost two weeks.) But a powerful frame was still implied beneath the dark suit; when quietly demurring on comments about his push from the federal prosecutor's office, he resembled nothing so much as a wounded bear. His elbows had returned to his knees.

Any hint of wistfulness evaporated as questions turned to the task before him. The city was confronting a spike in murders, particularly in poor, minority neighborhoods. "I'm a believer in the 'broken window' doctrine of crime and community," he says, "and job one is for us to increase our foot patrols and community policing."

That sensibility—and his practice of federal-local collaborative crime-bustingwas precisely what Mayor Gavin Newsom cited when asked why he had tapped a solid conservative who had been so resented by local liberal bigwigs: "Kevin Ryan," he said at the time, "will excel at collaborating with our partners in the criminal justice system—I mean police, prosecutors, public defenders and judges—because he has worked closely with them for years."

Besides community policing, and equally informed by the partnerships he forged when serving as federal prosecutor, Ryan stresses the need to update an antiquated communications system. A rickety radio network has potentially dire implications for an area prone to earthquakes and home to such potential terrorist magnets as Silicon Valley, the Transamerica Pyramid and the Golden Gate Bridge. "We're target-rich," he says.

He also worries about the everyday harm of outdated technology. "Think about this," he says. 'Almost 30 percent of our probationers are from outside San Francisco. We're a destination for some people who come here and commit felony crimes. So then we end up supervising their probation back in the [Central] Valley. Unless we have a modernized computer and data analysis approach, we're only solving half the problem. The challenge is that we have a city deficit of more than $330 million this year. But there's no choice, because on the [telecommunications] side, our infrastructure is inferior to what you'd find in [much smaller] Stockton. I'm not kidding." Even in the best case, however, Ryan concedes that a modernized installation is "realistically, a year away."

Realism, if that's the right word, colors his ruminations more than those who have branded him an ideologue might expect. At least one observer is not surprised. "What people don't understand about Kevin," says Rory Little, a former federal prosecutor in the Clinton administration who now teaches at UC Hastings College of Law, "is that you can't find a stronger supporter of the Bush administration agenda. But he's a real Boy Scout."

On immigration, Ryan says he opposes "mass deportation," insisting that policies should be "behavior-based" by focusing on attendant criminality and violence more than green card sweeps. Although he expresses support for capital punishment, he is quick to add his concerns about its "differential application."

Even on the much-derided Patriot Act and its progeny, Ryan offers tempering words. "I am most concerned about this wall we have between counterintelligence and law enforcement," he says. "We're up against a sophisticated, transnational movement that is a more-than-theoretical threat to American lives. But am I worried about rogue agents? Sure. And, of course, there has to be judicial oversight."

Mellowing with age? Chastened by his federal fall? "You've got to remember something," says Mayoral Chief of Staff Phil Ginsburg '89. "In any other city in America Kevin would not be considered a raging conservative. Plus the guy just plain knows what he's doing."

In the end that's the answer to Ryan's own quandary about his return to law enforcement. "Did you ever see Rocky VI?" he asks rhetorically. "I think it's the same for me as for that character." He pats his stomach. "I've still got stuff in my basement."

Arrested Development In 2005 the JusticeDepartment describedRyan as one of the"strong U.S. attorneyswho have produced,managed well andexhibited loyalty to thepresident and attorneygeneral." Two yearslater he was fired. Herehe announces the 2002capture of a SymbioneseLiberation Army fugitive.

NOW FIGHTING CRIME IN SAN FRANCISCO,RYAN SAYS, "JOB ONE IS FOR US TOINCREASE OUR COMMUNITY POLICING."

DIRK OLIN, executive director of the Instituteof Judicial Studies in New York City, is a frequentcontributor to DAM.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

COVER STORY

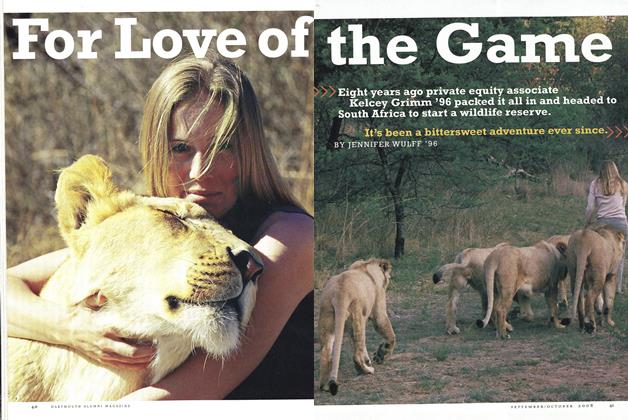

COVER STORYFor Love of the Game

September | October 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureIn Their Own Words

September | October 2008 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2008 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2008 By Kristen STromber '94 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2008 By BONNIE BARBER -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSWeathering the Storm

September | October 2008 By Diederik Vandewalle

DIRK OLIN ’81

-

Cover Story

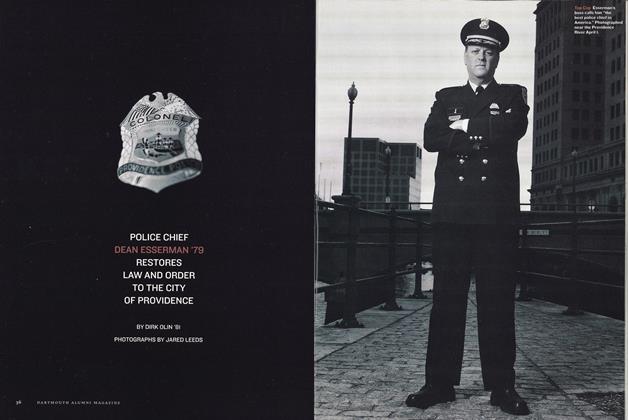

Cover StoryPolice Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence

July/August 2005 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Cover Story

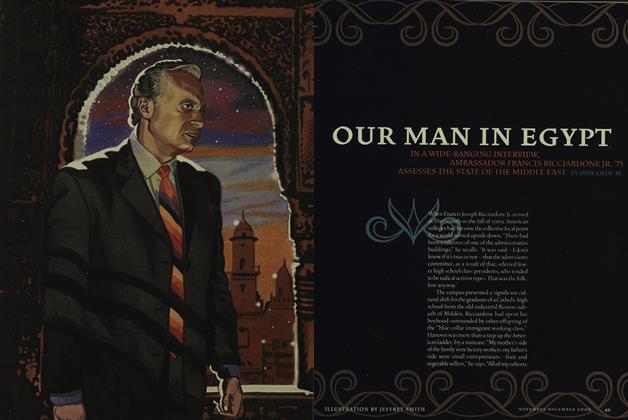

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

Nov/Dec 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

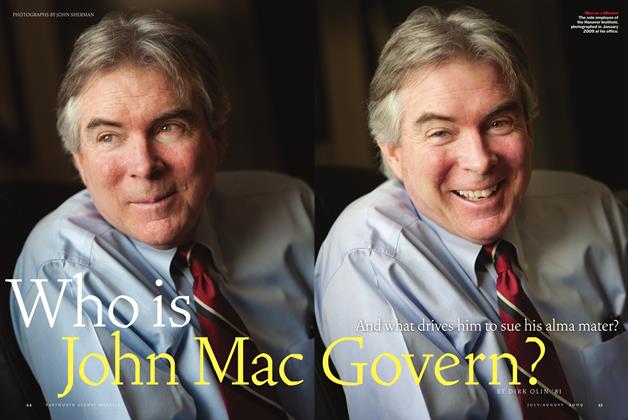

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July/Aug 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

Cover Story

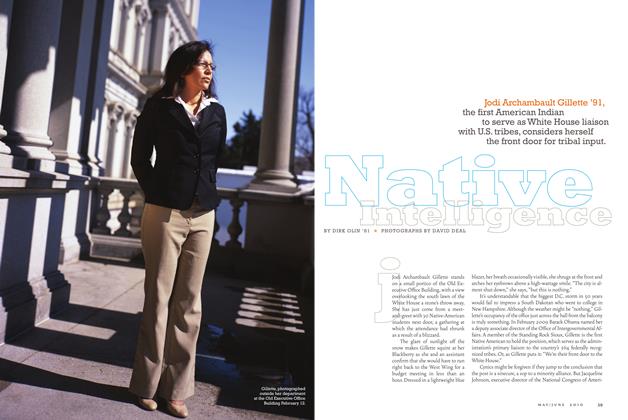

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reluctant Luddite

Sept/Oct 2011 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Article

ArticleSpecial K

MAY | JUNE By Dirk Olin ’81

Features

-

Feature

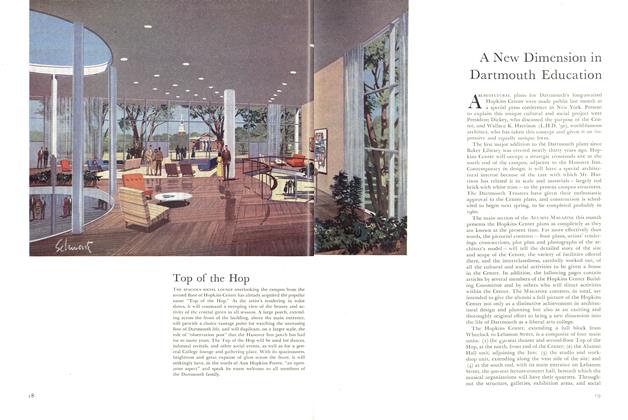

FeatureA New Dimension in Dartmouth Education

MAY 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Fellows: Seventeen Paths to Independent learning

MARCH 1966 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySENIOR CANE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureHitting His Stride

February 1992 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Unmysterious Bible

FEBRUARY • 1988 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mount Washington

NOVEMBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96