In Their Own Words

Excerpts from their admissions essays offer a glimpse into the lives and interests of eight incoming freshmen.

Sept/Oct 2008Excerpts from their admissions essays offer a glimpse into the lives and interests of eight incoming freshmen.

Sept/Oct 2008For years high school students have agonized over their college application essays, worrying that their carefully crafted words might make all the difference in gaining admission to their school of choice.

In reality, the essay is only part of the equation. "We don't have an assigned value for any aspect of a students application," explains Maria Laskaris '84, Dartmouth's dean of admissions and financial aid. "It's the combination of all the pieces that matters."

All applicants submit an essay via the "common app," an application form now used by more than 300 public and private colleges and universities. Students must write a minimum of 250 words and choose from six essay topic options. Four choices ask an applicant to describe one of the following: a significant experience, achievement, risk or ethical dilemma; a personal, local, national or international concern; a person; or a character in fiction, a historical figure or a creative work.

Another option asks students to describe an experience that illustrates what they would bring to the diversity of a college community or to tell of an encounter that "demonstrated the importance of diversity to you." Finally, students can elect to write about a topic of their choice, which is the most popular choice for Dartmouth applicants.

Do typos matter?

"Some people might think we'd automatically disqualify someone who didn't catch a mistake in spelling or punctuation, but that's not the way we read an applicant's personal statement," says Laskaris. "We are impressed by someone who writes an essay that makes us think 'this is an interesting person' or 'here's a person who has had a challenging experience and has demonstrated real growth as a result.' It's clear that some applicants have a real gift for writing. However, I believe that all students have something important to say about who they are and what has been most meaningful to them."

Typically two or three admissions officers read each application. Since personal interviews no longer factor into the admissions process, applicants may feel more pressure to convey in their essays what kind of people they are, but Laskaris says essays haven't changed all that much through the years. "There are themes that change from one year to the next in response to things that happen globally, nationally or locally," she says. "More often applicants write about a person—usually a family member—who has greatly influenced them or about overcoming a challenge."

We asked Laskaris to share with us a sampling of essays submitted by members of the class of 2012. With their permission, we present excerpts from eight students.

As a successful high school student I have been accused of simply being good at anything I attempt without trying or risking anything. This, however, is far from the truth.

I'll invest time and risk making a fool of myself in trying something new if I feel there is any chance of enjoyment for me in the long run. In eighth grade I made my first foray into a realm for which I was completely unprepared. The band room may not seem the most imposing of classrooms, but for me on the first day of eighth grade it was. I had signed up to try something completely new, and I was petrified. For the first time, I had the experience of being the worst. I literally couldn't play because I was too terrified of making a mistake. To be handicapped by one's own need to be right is agonizing. At this point I could have retreated, gone back to eighth grade academia with only a few painful memories to show for it. But, instead, a seed was planted in my brain, an inkling that failure could be wonderful. In the band room, amongst the snare drums, timpani and cymbals, I began to grow as a person. Never again did I want to be hemmed in by my fear of failure.

REBECCA RAPE, 17 SHERIDAN, WYOMING

My hands grasped the maple wood bench inside of the dimly lit courtroom. The judge lifted her gavel and delivered a bang that temporarily impaired my hearing. 'Nicole, I declare you a member of the Newman family,' she roared. Although I do not remember the phrase completely, I knew that my affiliation with a family unit would change my course of history forever. I would no longer have to be both mother and daughter. I would no longer have to wonder about my needs and exactly how I would procure them. I smiled from ear to ear as I marched down the aisle and onto the elevator—with my family following me. As I stood in the elevator unwanted memories took me back to a time in elementary school: "Nicole, Nicole! If all of the other students in my class can make a family tree, so can you," my teacher shouted. "Everyone has a family, dear. If you continue like this I'll be forced to give you a big, fat F." I stood at the front of her desk in disbelief, thinking that all of the other children lied about their identities. Didn't everyone live in a group home? That afternoon I was forced to present the awkward discussion of foster care to my fellow pupils. I could predict the name calling that would soon commence.

NICOLE NEWMAN, 19 ASBURY PARK, NEW JERSEY

For most of the winter they lie dormant, curled up in their snug little house, well fed and willfully ignorant of the frigid weather that surrounds them, seeming to survive simply because they won't admit they should be dead. These fascinating creatures dance instead of talk and mate hundreds at a time, hundreds of feet in the air. They build their own home and literally die in its defense. There are a few of us who find them truly fascinating, and we call ourselves beekeepers.

The first thing I notice when I begin preparing to open my hive is the faint aroma of wax and honey that clings to my bee suit. It sends my thoughts back to the first time I saw the inside of a hive. I dressed in the old, paint-spattered one-piece zip-up bee suit I would come to love, a pair of stiff and cracked leather gloves, and what can only be described as a screened-in safari hat. With a mixture of apprehension and excitement I proceeded to the hives. When my mentor and I opened the first hive I was struck not only by the astonishing number of bees, but by the sudden low thrum that is the sound of a functioning hive. One of my favorite experiences has since become to sit beside my hive and feel the resonance of the thousands of tiny lives struggling so hard to survive. This quiet hum, like the noise of a busy street, is rich with the energy of life.

SAM ROSS, 18 HINESBURG, VERMONT

I grew up in Baghdad. In June 2002 I was one of 50 students accepted at Nahrain University College of Medicine. I ranked eighth out of 600 applicants. I seemed to be on the road to success.

All that changed in March 2003. Baghdad became a war zone. The roads to college were unsafe and I was risking my life by going there. When the situation became too dangerous, my mother, brother and I fled to Syria to find some peace. But life in Syria was more difficult than we thought. The costs of living were very high, and Iraqis weren't granted work permits.

On the last day of 2006 my father was shot and killed by terrorists in Iraq. He had been a UNICEF staffer since 1999. After two months of grief I realized there was no point of living in sorrow and decided I needed to do more with my life; something my father would have been proud of me for doing. I became a volunteer at a center near my home, which was run by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd to assist Iraqi refugees in my neighborhood. I became more involved in their work and I was assigned as a secretary, translator and social worker. Seven months later I was offered a job with United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) as assistant team leader in a community services center in my area. I strongly feel that given the opportunity we can all contribute to society in a positive way, no matter what tragedies we have faced.

SARAH JANAN AZIZ, 23 BAGHDAD, IRAQ

As music blares out of the speakers, my body twists and turns to every beat and rhythmic sound. With every spin and turn my worries of the day whirl out of my mind. This daily routine is a secret I've kept from friends and family. I cannot imagine my life without dancing.

Dancing is my passion, my therapy and my connection to my country's culture. When I was a five-year-old immigrating to America the thought never crossed my mind that I would not be returning to Cape Verde and see the familiar sights and people that I had grown accustomed to. The only way to experience Cape Verde now is through my parents' stories. I miss being somewhere where I can hear other people speak my language and participate in my country's customs.

From a young age I felt there was a lost connection between my culture and my place in it. Was I Cape Verdean? American? Or Cape Verdean-American? I found that I was at a loss when it came to defining myself. Recently I've mended this damaged connection through dance. By teaching myself how to dance traditional and contemporary dances of the island of Cape Verde—pasada, colagicion and funana—I've found a place where I belong.

ANA SOFIA DE BRITO, 17 PAWTUCKET, RHODE ISLAND

I am a soldier currently [September 2007] deployed to Camp Ramadi, Iraq. As a psychological operations specialist, my job is to influence the local populace to change its behaviors and attitudes in favor of Coalition objectives. Policy makers and some think tanks attribute the Iraqi reconstruction quagmire to corruption by coalition troops during the occupation as much as to insurgent sabotage. There may be some unfortunate truth to this. However, a great obstacle to the successful reconstruction of this war-torn nation is the victim mentality of many Iraqis [who are] inclined to remain sedentary and apathetic for two reasons. First, they know only a subsidized economy. Food, water and electricity have always been there for them. Second they feel because the United States invaded and has the means to support them, that they are the victims of a tragedy and are entitled to a just reward. To address the failing reconstruction of Iraq, we must embrace the tribal quality of Iraqi culture and call upon the sheiks and other local leaders to make the necessary movements toward a safe, free and responsible Iraq.

TYSON DEMAREST, 21 LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS

When I was 10 a teacher explained that people are paid to go to restaurants, eat, and write about food in delicious detail. In their stories dark, cream chocolate oozed, cinnamon scented the air, and the sheer beauty moved the writers and me. I had people!

My art is culinary; it's creating delectable and beautiful confections, tasting the subtle differences between cumin and coriander in a dish and gently employing food to win friends and influence people.

I was a kid who understood cake in a home where no one baked. So baking became my first sustained passion. Baking has always served me well as a common language in a new situation.

Arriving for a year in France at a time when Americans weren't popular, I learned that American foods were. Sunday pancake breakfasts and American-style picnics at the park across from my house helped me bond with my host family. Locals would stop, talk and try my dessert de jour. I became the best-tolerated American among my host sisters college friends, and even my international ultimate Frisbee team warmed up when I brought apple pies. Scholars will one day document that what was served at State Dinners had substantial impact on foreign relations throughout history.

BLAIR BANDEEN, 18 SHELL BEACH, CALIFORNIA

I remember being curious about an old picture of my grandmother wearing what I thought was a funny costume. I asked why Grandmother was dressed like that, with a feather in her hair. My father explained that his mother was a Mohegan Indian, that she was dressed in regalia for a special occasion and that the photograph had been taken by someone who was studying Indians.

My father showed me some later pictures of his mother, including one of her in a fine automobile, which she had bought with her earnings as a telephone operator. He told me how modern and independent she had been as a young woman.

I had begun to learn about being a Mohegan. The Mohegan Tribe has preserved its identity and grown strong by adapting to change while remembering and drawing guidance from the past—traditions reflected by the contrasting photographs of my grandmother.

I learned how my grandmother and others in the tribe had long pursued land claim settlements and federal recognition. The efforts seemed hopeless at times. As I grew up, however, the tribe achieved one amazing milestone after another. The challenge for a young Mohegan like me would be handling success.

All that's been accomplished by my ancestors inspires me. I feel a liberal arts education would best prepare me to do as the tribe has done: to learn from the past, to learn how to cultivate good personal relationships and political alliances, and to learn how to think in order to adapt to whatever changes and opportunities the future might bring.

DEREK T. FISH, 18 MADISON, CONNECTICUT

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

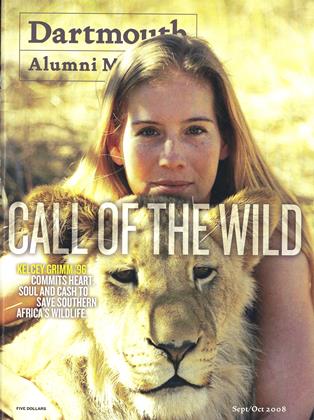

COVER STORY

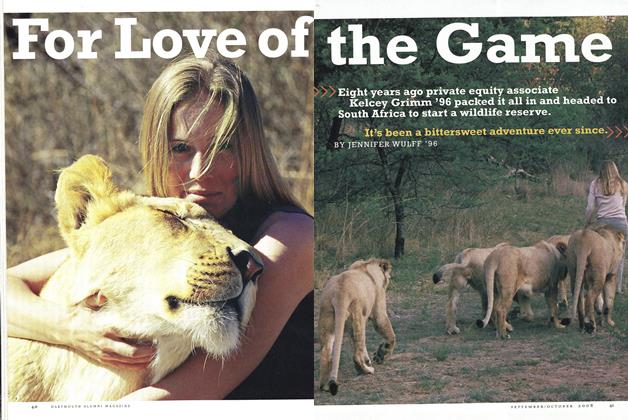

COVER STORYFor Love of the Game

September | October 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

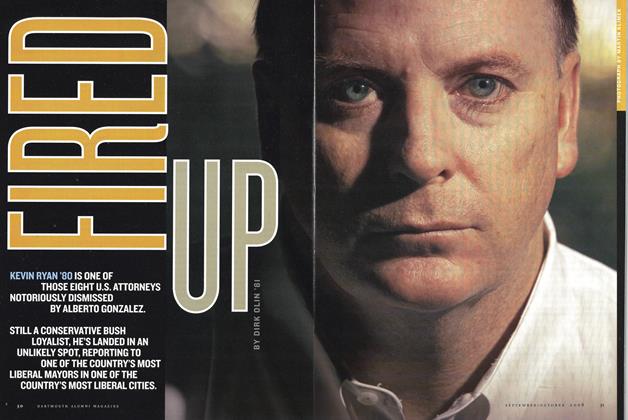

FeatureFired Up

September | October 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2008 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2008 By Kristen STromber '94 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2008 By BONNIE BARBER -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSWeathering the Storm

September | October 2008 By Diederik Vandewalle

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCOMMENCEMENT

June • 1985 -

Feature

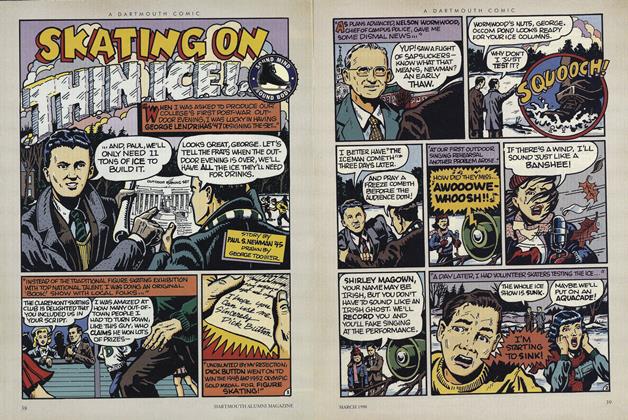

FeatureSKATING ON THIN ICE!

March 1998 -

Feature

FeatureFrom America's Lost Cohort, the Shards of Souls

SEPTEMBER 1988 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

JUNE 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Feature

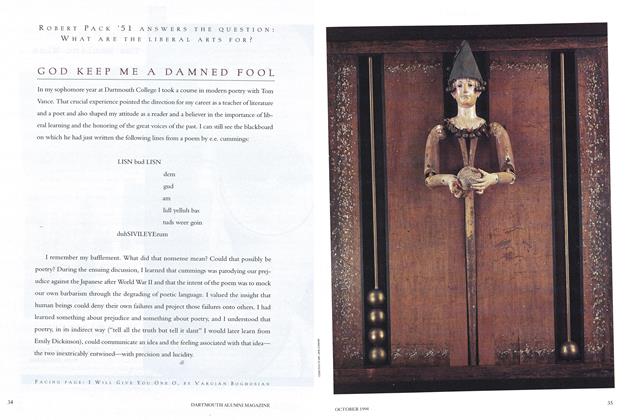

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

OCTOBER 1994 By Varujan Boghosian