Weathering the Storm

A government professor reflects on a recent visit to troubled Myanmar, a closed country devastated by last May’s cyclone.

Sept/Oct 2008 Diederik VandewalleA government professor reflects on a recent visit to troubled Myanmar, a closed country devastated by last May’s cyclone.

Sept/Oct 2008 Diederik VandewalleA government professor reflects on a recent visit to troubled Myanmar, a closed country devastated by last May's cyclone.

ON MARCH 7 THIS YEAR I QUIETLY SLIPPED OUT OF THE TRADERS HOTEL IN Yangon to take some early morning pictures of the city's crumbling colonial architecture. Together with a group of Dartmouth alums I had arrived the evening before in the city formerly known as Rangoon for a trip around Myanmar, one of Southeast Asia's most forbidding countries. Not far from the hotel, at a local bus stop where men and women clambered aboard rickety buses that serve as part of Yangon's antiquated transportation system, I photographed a young Buddhist monk in his dark burgundy robe against the backdrop of what had once been a distinguished Edwardian townhouse, a legacy of the British colonial period, now painted a vivid green.

Almost two months later, on a lazy Saturday morning in Hanover, while reading The New York Times I was shocked to see a picture of the same building on the front page. This time, however, the cameras lens had found no tranquil early morning scene but utter chaos, as people were trying to clear away with their bare hands the first piles of debris from Cyclone Nargis, one of the most powerful storms to hit Yangon and the Irrawaddy Delta in recorded history. The flat plains of the delta, former swampland that was converted during British colonial times into a rice-growing area, were once known as the rice bowl of Asia. The plains stretch for hundreds of miles away from the Andaman Sea, and the 12- to 20-foot floods unleashed by Nargis left a catastrophic legacy of death and destruction that instantly transmogrified itself into a major humanitarian disaster for Myanmar.

Satellite pictures taken before and after the cyclone showed the almost surreal extent of flooding and destruction that had taken place. Yangon, at best a ramshackle place that relies on private generators in the absence of reliable government-supplied electricity, came to a halt.

Most Myanmar watchers held their breath. Would the tragedy once more jolt the population and the country's monks, in particular, into action against a regime that has kept itself in power by brute force since 1962, voiding open elections that were held in 1990 and won by Aung San Suu Kyi's opposition party? Only months before, in September 2007, the country's army and police forces had bloodily suppressed demonstrations led by hundreds of monks that had been sparked by increases in food and fuel prices. Also, how would the notoriously xenophobic junta, now safely ensconced in its recently finished jungle capital at Naypyidaw, react to aid efforts that could undercut its power?

The September 2007 riots represented only the latest incident in a conflict that has pitted the military against diverse groups and minorities in the country since its independence from Great Britain in 1948. These conflicts have economically ruined the country and made its rulers pariahs in the international community. Dartmouth's links to Myanmar (known as Burma until 1989) had been cultivated and maintained during the 1960s by geography professor Bob Huke '48, who provided expertise on rice cultivation to the government. In turn, Burmese professors had occasionally visited Dartmouth through the Fulbright program until that was cancelled after the military came to power.

David Halsted '63, one of the alums on the March trip, had been a political and economic counselor in Yangon for two years in the mid-1980s, when it was still called Rangoon. His reflections on how Myanmar had changed and simultaneously remained barnacled with its authoritarian political system provided a steady topic for discussion as we traveled to the Golden Rock in Kyaiktiyo (Myanmar s most sacred Buddhist shrine) and then on to the old capital of Mandalay, followed by Inle Lake and Bagan.The level of fear among the local population was subtle but profound. Our local guide, a gregarious man in his mid-40s who had worked for a state company until he was fired for being politically unreliable, studiously avoided attending the lectures I presented to the Dartmouth alums. The reason, he explained wearily in private, was to avoid being asked by security people to report on what had been said. Even being present, he said, would have made him politically suspect.

The days and weeks following the cyclone witnessed a flurry of interna- tional initiatives to bring food and shelter to an ever-growing number of refugees displaced by the storm. Confirmed deaths eventually ran into the tens of thousands and the number of refugees crowded into makeshift camps into the hundreds of thousands. Western nations, nongovernmental aid organizations and the United Nations all lined up to provide help with logistics and aid. Everyone waited.

Much to the consternation and outrage of the outside world, however, the regime initially refused to admit aid workers, and supplies trickled in only when the Myanmar military could control access and distribution points. International aid agencies and the UN at one point temporarily suspended deliveries when they were diverted by the Myanmar military or when the junta haggled over import duties on emergency supplies. To underscore the severity of the crisis as well as the concern of the international community, in late May, after almost three weeks of obstruction by the junta, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon traveled to the country to plead with the generals to speed up visa applications for international aid workers and to facilitate the delivery of international^supplies. Despite the junta leaders' promises, access remained difficult and subject to severe restrictions. After intense diplomatic efforts the USSEssex strike group finally left Myanmar waters, having failed to receive permission to unload its humanitarian cargo.

For the international community Myanmar poses a dilemma similar to that faced in North Korea and Zimbabwe: How to provide aid to people whose own government routinely spurns any outside assistance, while not wanting to appear as supporting an illegitimate and despised regime. Shielded by China and Thailand, with their enormous economic and political interests in Myanmar, General Than Shwe and the military junta once again avoided dealing with the country's pervasive problem of creating a true state out of dozens of ethnic groups. This tension between the country's central authority and diverse groups within historical Burma is in large part the result of the divide-and-rule policy the British adopted during the colonial period, playing different ethnic groups against the majority Burmese population.

In the brouhaha over the regimes inept handling of the cyclone disaster, the extension of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi's house arrest passed almost unnoticed. So did the meaningless approval of a "roadmap to democracy" referendum that, after a short interval, the regime insisted on holding despite the cyclone. Fearing another political backlash, the junta started to forcibly remove thousands of refugees from shelters and monasteries and repatriated them to an uncertain fate in villages and areas that had been ruined by the storm.

Many observers had hoped the disaster and the need for humanitarian aid would provide the opportunity for a renewed engagement between Myanmar and the West. So far that has not happened, and it seems unlikely. Despite the regimes incompetence and unwillingness to deal with the effects of Cyclone Nargis, it continues to portray itself as the only force that can hold Myanmar together, against both internal and external enemies. Aung San Suu Kyi represents only one of several groups in Myanmar—albeit the best organizedthat continue to oppose the regime. Several other ethnic groups have been in a constant low-level civil war since independence. Their existence, occasional confrontations with the regime and the support some have enjoyed by foreign countries (including the United States) have steeled the reserve of the Burmese generals to resist any attempt at compromise.

As we traveled throughout Myanmar our alumni group noticed many expressions of this xenophobia, expressed in dire warnings against both insiders and outsiders allegedly intent on destroying the country. In an Orwellian fashion that brings to mind North Korea or former Albania, these exhortations could usually be found on huge billboards, in red-and-white lettering, warning the population in English and in Burmese to be circumspect and suspicious, particularly of foreigners. Tourism in Myanmar, more than in many other countries, is a double-edged sword for the local junta. It may enrich the regime but, as we discovered throughout our trip, it also challenges the very stereotypes the regime tries to project to keep itself in power. And it provides glimpses, even if fleetingly, of the outside to a people who normally hear only the disembodied voice of its own capricious rulers.

Life Goes On Locals in Yangondrink tea undera tree felled byCyclone Nargis.

Despite the regimes incompetence, it portrays itself as the only force that can hold Myanmar together.

DIEDERIK VANDEWALLE is associateprofessor of government and former chair ofthe Asian and Middle East studies program.He has been a lecturer on several Dartmouthalumni trips throughout the world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

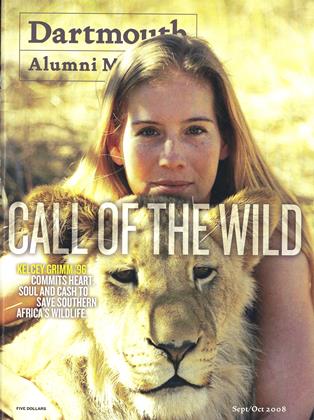

COVER STORY

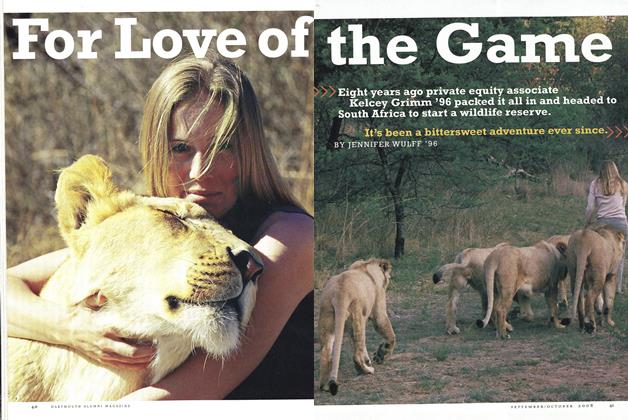

COVER STORYFor Love of the Game

September | October 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

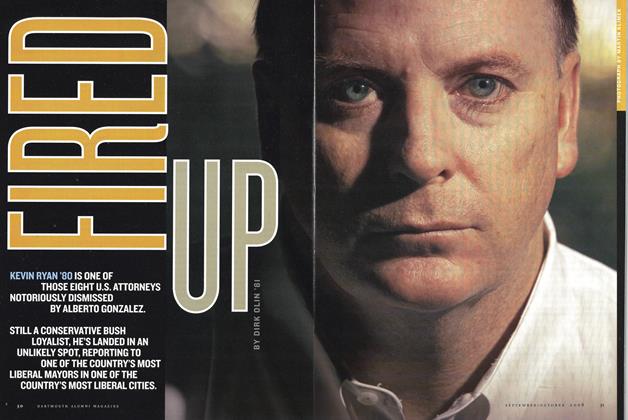

FeatureFired Up

September | October 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureIn Their Own Words

September | October 2008 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2008 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2008 By Kristen STromber '94 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2008 By BONNIE BARBER

OFF CAMPUS

-

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSShrimp, Sirloin, Sass

July/August 2006 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Off Campus

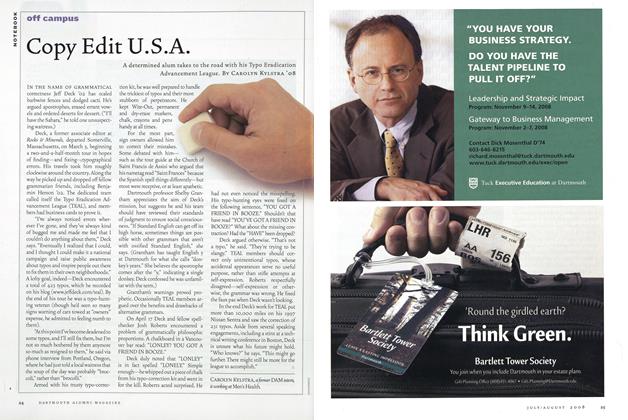

Off CampusCopy Edit U.S.A.

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSReturn of Pinto

Nov/Dec 2006 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSTrading Places

Jan/Feb 2013 By Judith Hertog -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSGlobal Thinker

July/Aug 2009 By Lauren Zeranski ’02