THE colleges of this country date from that small group which preceded the Revolution - Harvard, William and Mary, Yale, Princeton, Pennsylvania, Columbia, Brown, Rutgers, and Dartmouth,— each one coming into existence under the hard conditions of colonial life, to the group born in a day at the close of the last century and endowed with its wealth, of which Chicago, and Iceland Stanford are conspicuous examples. But whatever the date of their founding all existing colleges are modern in a common sense. The modernizing process has brought the whole college fraternity into substantial unity of purpose and method and especially of administration, the point of emphasis in this paper. This process does not reach back of the Civil War, and in most cases it has shown its results most clearly within the past decade.

I will state briefly the conditions which have necessitated the present attention to administrative work within our colleges. First, the 'vast increase in the subject matter of the higher education. One of the earlier contracts for instruction in Dartmouth College ran as follows. It bears date of November 9, 1777,

"An agreement between the Reverend Doctor Eleazar Wheelock, president of Dartmouth College, and Mr. John Smith, late tutor of the same, with respect to said Mr. Smith's settlement and salary in capacity of professor of the languages in Dartmouth College.

"Mr. Smith agrees to settle as Professor of English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Chaldee, etc., in Dartmouth College, to teach which, and as many of these and other such languages as he shall understand, as the Trustees shall judge necessary and practicable for one man, and also to read lectures 011 them, as often as the president, tutors, etc., with himself, shall judge profitable for the Seminary. He also agrees, while he can do it consistently, with his office as a Professor, annually to serve as tutor to a class of students in the College. In consideration of which, Dr. Wheelock agrees to give him (the said Mr. Smith) one hundred L. My. annually, as a salary to be paid one half in money and the other half in money or in necessary articles for a family."

We might set this extract aside as a quaint bit of the later mediævalism, were it not that Senator Hoar, in his " Reminiscences of Life at Harvard," says explicitly: "I do not think that Harvard College had changed very much when I entered it on my sixteenth birthday in the year 1842, in manners, character of students or teachers, or the course of instruction, for nearly a century. There were some elementary lectures and recitations in astronomy and mechanics, accompanied by a few experiments. But the students had no opportunity for laboratory work. There was a delightful course of instruction from Dr. Walker in ethics and metaphysics. There was also some instruction in modern languages—German, French, and Italian—all of very slight value. But the substance of the instruction consisted in learning to translate rather easy Latin and Greek, writing Latin, and courses in Algebra and Geometry, not very far advanced."

It was not, we must remind ourselves, till the first of October, 1859, that Mr. Darwin sent out his abstract, as he termed it, on the "Origin of Species," accompanying the volume with the modest prophecy, "that when the views entertained in this volume, or analogous views, are generally admitted we can dimly foresee that there will be a considerable revolution in natural history."

From the philosophical point of view, account had to be made at once of the revolutionary character of modern thought, but from the administrative point of view account had to be taken of its marvelous expansion. Within our generation the subject matter of the college discipline has trebled in volume, through the incoming of the sciences with the scientific method, and through the incoming of the new '' humanities '' based upon history with its application to economics, politics, and sociology, and upon the modern languages and literatures. This trebled volume of knowledge has been made workable through the principle of electives, a matter very largely of administration. More study is called for today in the construction of a curriculum in our schools and colleges than in any one department of investigation or instruction.

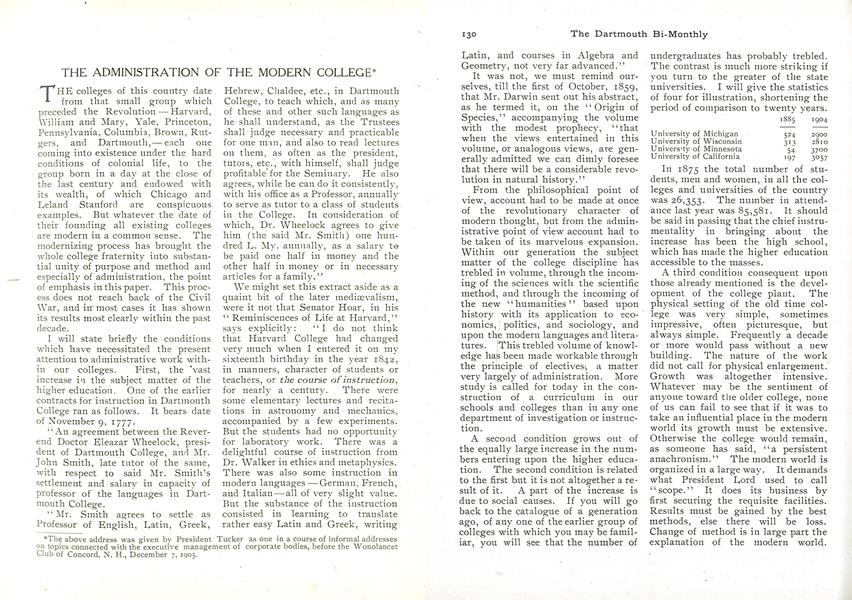

A second condition grows out of the equally large increase in the numbers entering upon the higher education. The second condition is related to the first but it is not altogether a result of it. A part of the increase is due to social causes. If you will go back to the catalogue of a generation ago, of any one of the earlier group of colleges with which you may be familiar, you will see that the number of undergraduates has probably trebled. The contrast is much more striking if you turn to the greater of the state universities. I will give the statistics of four for illustration, shortening the period of comparison to twenty years.

1885 1904 University of Michigan 524 2900 University of Wisconsin 313 2810 University of Minnesota 54 3700 University of California 197 3057

In 1875 the total number of students, men and women, in all the colleges and universities of the country was 26,353. The number in attendance last year was 85,581. It should be said in passing that the chief instrumentality in bringing about the increase has been the high school, which has made the higher education accessible to the masses.

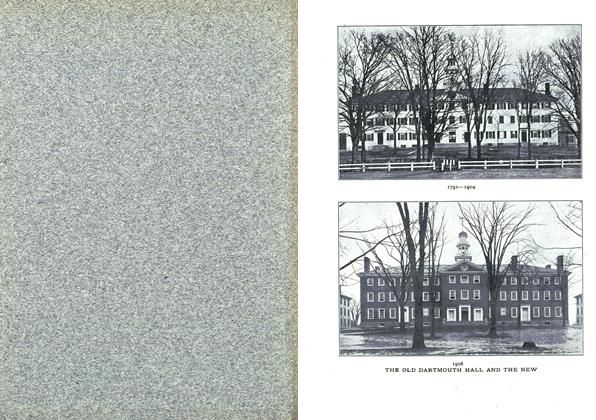

A third condition consequent upon those already mentioned is the development of the college plant. The physical setting of the old time college was very simple, sometimes impressive, often picturesque, but always simple. Frequently a decade or more would pass without a new building. The nature of the work did not call for physical enlargement. Growth was altogether intensive. Whatever may be the sentiment of anyone toward tlie older college, none of us can fail to see that if it was to take an influential place in the modern world its growth must be extensive. Otherwise the college would remain, as someone has said, "a persistent anachronism." The modern world is organized in a large way. It demands what President Lord used to call "scope." It does its business by first securing the requisite facilities. Results must be gained by the best methods, else there will be loss. Change of method is in large part the explanation of the modern world. We live,differently, we work differently, we think differently. As Mr. Balfour has recently reminded us, we are obliged to do our thinking "in a new mental framework."

The modern college plant is an outcome of the change of method in education, and of certain changes in social life. The laboratory is not another college building, but a new and typical building. A college dormitory is no longer so many rooms. A house without steam, or electricity, or a bathroom, is a house, but you do not build houses that way to put upon the market. A college plant may consist of more than educational facilities. It may be obliged to create certain public utilities to insure proper sanitation, or general conveniences. The college of the country not infrequently owns in part or wholly its water supply, its heating and electric plant, its system of sewage, and very likely may be obliged to own and maintain an inn for the special benefit of the alumni and guests of the college. I will refer .later to the financial bearings, of the college plant. For the moment, I speak of it as a very great factor in college administration.

A fourth condition affecting incidentally the administration of the modern college is the incorporation of the alumni through their authorized representatives into the governing board. Alumni representation is in some form characteristic of every college which is self governed, and it is beginning to find a place in institutions governed by the state. Representation on the governing board changes the relation of the alumni from that of sentiment to that of responsibility. It virtually unifies the whole body academic, In the old walled cities there are places known as so and so "within and without." Every college today has its "within and without," but they are one. And in their oneness very much of the new power of a college lies. The responsible cooperation of the alumni creates certain mutual obligations which ought to be recognized and acknowledged in the whole sphere of administration.

These are some of the conditions which have given a prominence to administration in academic life far beyond any former recognition of its necessity or value. I am asked to show what the administration of the modern college means, in what it consists, toward what ends it is set. In answering this question I shall have very little to say about college administrators, not out of modesty, but because they cannot be described as a class. College presidents belong to the order of Melchisedic, that is, they are without parentage. No one knows where the next president of any college is to come from. He may or may not be a member of the board of trustees, or of the faculty. He may or may not be a graduate of the college. He may be a minister, or a layman, and if a layman a man from some one of the professions, or a man of affairs. The assumption is that he will be familiar with some phase of the higher education, but this presumption does not have the force of a requirement. There is nothing to say about college presidents in the abstract. No two men are set to the same task. "Every man must bear his own burden." One of the most efficient of the younger college presidents in the West, went to Mark Hopkins for advice, on his first election to office. "Not a word of advice will I give you," said the wise old counsellor, "you will do better to find out things for yourself."

But the administration of a college is something very definite and tangible, very real in its objects, and reasonably well defined in its methods. In answering then the first question which naturally arises in your minds - what is the chief concern in college administration?—I say, without a moment's hesitation, the student.

Colleges and universities are great human institutions. Colleges are for men not men for colleges. It is only by keeping this fact constantly and sensitively in mind that we can keep our institutions of learning from institutionalism. This concern of college administration for some fit outcome in the individual student expresses itself in various forms. Speaking broadly, very broadly, the German university has in mind the scholar, the English college the gentleman, the American college and university the citizen. This generalization if pressed too far becomes untrue. But it is" sufficiently evident to indicate the task before our colleges and universities, namely to educate a democracy. It would be a far more congenial task to most of those upon our faculties to educate the scholar after the German fashion, it would be a far easier task to determine the social standards of a college through those rigid inquiries which guard the entrance to academic life at Oxford and Cambridge, but it would not be our task. Our task is more difficult because of its breadth. We are set to the task of taking the average product of a democracy, of qualifying as much of it as possible for independent scholarship, of moulding as much of it as possible into the habit of the gentleman, and of fitting it by all the means and incentives at command for the high estate of influential citizenship. Whatever is done toward these, or any other ends, must be done in consistency with personal freedom. Personal freedom is the keynote of college life. Paternalism will destroy the moral power of any college. Where it saves one it weakens and demoralizes the whole body. Personality is always a timely and inspiring force. But this must somehow be incorporated into the spirit of the college itself. It must never be a separate thing. A college is a world of incentives and tests, with corresponding temptations. Not all can live to best advantage in this world. The process of elimination is constantly going on. It is a part of the business of administration to supply incentives, mental and moral, to create a healthful and bracing atmosphere, but equally to maintain standards. Nothing is so costly in college administration as any lowering of its standards in the assumed interest of those who cannot or will not accept them.

There is one feature of college administration in its relation to student life which is apt to be overlooked, namely,the necessity for takingaccount of leisure as well as of work. It is the recognition of this fact which has let in or brought in organized athletics to the modern college. Athletics has proved to be the best employment of the leisure of a college which has been devised. It has displaced a very considerable amount of mere idleness and of gross dissipation. I lay more stress upon its mental than upon its physical effect. Physically, organized athletics affect the few, mentally they affect the whole body of students. I am well aware of the charge of mental preoccupation. The charge is true, but on the whole I would rather take my chance, were I an instructor, with the student who comes into the classroom from talk about the game, than with one whose leisure would be pretty sure to be occupied with more frivolous or more demoralizing talk. I heard it said a day or two since that "athletics had cleansed and dulled the mind of a college." I think that athletics has done far more "to cleanse" than "to dull." The cleansing of mind is evident. If the mind of a college is dull in its appetite for knowledge, by comparison with the reported zest of earlier times, I think that there are nearer and more evident reasons for this dullness than are to be found in athletics. In this general view, I am sustained by the practically unanimous opinion of the older members of the faculty at Dartmouth, who are able to compare earlier with later periods of college activities.

Having had this much to say about athletics in general, I cannot fairly pass over the immediate question in college athletics now before the public mind. I have always taken a certain pride in football as the most distinctively academic among our national games. I have noted the fact that it has not been taken up as a sport by the rougher elements in our cities. The reasons for this surprising fact seem to me to lie in the game itself. It is so strenuous, it requires so clean a physical condition, it demands so much mental tension, and so much willingness to sacrifice individual choice to the good of the team, that it would be almost impossible to find men able and willing to play the game outside our colleges. I should not want to see a game with these strong and really noble features ruled out in favor of weaker and less invigorating games. The two serious charges against the game are dishonesty and brutality - dishonesty in making up the team, brutality in the playing of the game. There has been a very great gain at both these points through the continuous efforts of the better athletic committees in our colleges, but if more definite and more general action is required I should advise the interference of the college authorities at each of these points. Let there be an intercollegiate committee appointed by the faculties which shall pass upon all personal questions of eligibility as a board of examiners would pass upon candidates for admission to college, and further let the umpires of the games be entirely in the employ of the college authorities with arbitrary power to control the game, affixing and using such penalties as may guarantee its character. A certain element of danger, of course, remains, as in any sport, and in many kinds of work, but the danger diminishes with attention to the physical condition of the men, and with the skill of the team. Football is not a small boy's game, neither as it seems to me, for other reasons, is it a game which fits into the life of our professional schools.

Next to that concern in the administration of a college which centers in the student I should say that the most direct and constant interest was to facilitate the work of instruction. It is the direct function of the administration of a college to make it possible for every member of a faculty to do his work to the best advantage within the limitations of mutual service, and within the restrictions of the ordinary financial stringency.

The first step in facilitating the work of instruction is taken by relieving the faculty as a whole of the details of executive work. The result is effected in two ways, by putting the routine of the internal life of the college in charge of one person, and by delegating as much of remaining details as possible to standing committees. The dean of a modern college controls the daily movement of its life. He sets the time of day. Personally he is concerned with the immediate relation of the college to the students, but his offices are business offices where all the routine of administration goes OIL Every day's work is put on record. The standing of any student can be seen at a glance by those entitled to know. The office is a clearing house for the departments.

Committee work is irksome or enjoyable according to the taste of the individual instructor. Faculties as a whole, and individual members, vary in their desire or reluctance to relinquish the control of details, especially those details which are most intimately connected with students. The most obstructive detail is discipline ; but as college discipline is now almost entirely connected with deficiences and failures in scholarship it remains; of course a matter of interest to instructors. The tendency, however, is to delegate discipline, of all kinds, to some fit committee. Virtually the authority of the faculty is exercised and declared through delegated power, leaving the faculty as a body comparatively free for the discussion of educational topics. This statement should be qualified by the fact that there has come in a very great increase of executive work in connection with the departments. Bach department must be organized according to its own needs. With the growth of a college there must be a large increase in "directive power." Careful organization is. the chief means of saving waste and facilitating work.

Beyond this the work of instruction is dependent for its efficiency upon the general resources of the college, upon the special equipment of a department, and upon the amount of assistance, particularly the last. The constant and perplexing quesion of administration is how to keep the right proportion between instructors and students. There is no unit of measurement here. Everything depends upon the nature of the work, and the intellectual ability of the student. There is no such thing as an average student upon whom you can base a calculation. Students are of all grades intellectually. The poorest students require the most instruction, that is, there must be smaller divisions if they are grouped; and the best students of most advanced work deserve most attention at the hands of an instructor, that is, there must be smaller divisions again if they are grouped. It may be the greatest educational economy to give a disproportionate part of the time of the best instructor in a department to directing the study of five men.

And in the distribution of the time of an instructor regard must be had to his Own intellectual advancement. I am not speaking now of the research work of a university nor of the technical work of a professional school. Every college professor should have time and opportunity for research, investigation, original work of some kind. This again is a part of the economy of a college. Perhaps the nearest approach to a fit opportunity for personal advancement lies in the Sabbatical year now granted in all of the better colleges.

A new and rapidly growing department of administration lies in the relation of a college to its constituency, the alumni, the parents and friends of students, the state, and the public at large so far as its interests extend. Every college has also its intercollegiate relations. It is a part of a vast educational system. Of course it is the office of one who may be the head of a college to represent it on public occasions, to declare its policy, and to adjust its formal relations to other educational bodies. The direct connection of parents with the college is through the dean's office. But between these there lies a wide reach of administrative work now covered by a new officer, namely, the secretary of the college, whose business it is to present the college in proper ways to its constituency, through correspondence, through publications, and as occasion may offer through personal intercourse with those who are concerned with the affairs of the college. At Dartmouth the secretary of the college is the general secretary of the secretaries of classes and of alumni organizations. This department, as I have said, is recent even in the colleges where it has been formed, but it illustrates the growth of purely administrative work.

I pass through this department of administration to that which is represented by the governing board, namely, the financial management Of a college. The universities of Germany are under the financial control of the state. The English colleges are managed much more completely from within. The American college or university is under the control of the state, or of a corporate body usually self-perpetuating, except as modified by alumni representation. I refer in what follows to the financial management of endowed colleges under the control of boards of trust. These boards vary in size. The original idea seems to have been that of large representation. The modern idea is efficiency. It may safely be assumed that the efficiency of a board is in inverse ratio to its size.

As you may at once infer the colleges of the country were quite unprepared financially for the new burdens which were to fall upon them through the increase in the number of students and through the increased cost of education, due to change of method and to the augmented volume of subject matter. Furthermore it. was manifestly impossible to increase endowments to keep pace with the new demands, especially in view of declining rates of interest. The saving idea which came in was the development of the college plant, through which the college might increase its own earning power. This development of the college plant as a means of financial aid marks the advance in the financial treatment of the modern college. Money apparently sunk in buildings and equipment reappears in greatly enlarged income through tuition. In the larger colleges the receipts from tuition are now equal to or greater than the income from invested funds. In many cases the earning power of an institution has increased fivefold within a generation, or even within a decade.

It is also true that as the necessities of colleges and universities became apparent, and much more as their capacity became apparent, they became the recipients of large gifts. The period just passed has been a period of endowment, as well as of increased earning power. The question naturally arises, will the wealth of the nation be permanently interested in education, or more exactly, in existing educational institutions. The answer seems to me very doubtful. The interests of wealth are changeable, especially those of men of sudden and vast wealth. There are indications that the interests of wealth are either centering in great educational trusts, or are passing over to other and newer objects of benefaction, perhaps in the region of the arts. Account must also be made of the growing desire of men of wealth to found families. Great enterprises also require great reserves of capital. In any event I believe that the financial future of a college does not He in some lucky access to money at large, but in its stead}' access to permanently interested money. Soon or late every college must fall back for its support upon those who belong to it by inheritance, or association, or indebtedness. Nothing has been more suggestive at this point, or more inspiriting than the quiet but prompt response of the alumni of Harvard to the recent call for a fund of two and a half millions. This, I say, is suggestive of the future sources of financial aid to our colleges. The permanent source of supply is interested money. It is this interest which has made the appropriation of the State of New Hampshire to Dartmouth College for the past years, the income of half a million, of so much value to the College. The heart of the State has gone with it. It is this interest which made the gift of Edward Tuck of three quarters of a million of such value to the College. His heart was in it. It is through this avenue of possible interest that Dartmouth or any college has the right to approach any man of means whom it would like to identify with itself. I believe that a college has no right to ask any man for his money when it simply wants his money but does not want him. That sort of business is not fair play. An invitation to give ought to be also an invitation to come. The roll of the benefactors of .a college should be such as to be accounted as much an integral part of its life as the roll of its graduates.

As the trustees of a college turn from the sources of financial supply to the needs of the college, there are two constant and pressing needs which differ from others. There is always the demand for something of better quality or of larger amount. It is a trite but honorable saying that it is the business of a college to be poor. When it has no wants which outrun its income, it is a serious question about its inner life. But the needs to which I now refer come with a personal pressure. The first has to do with the pay of competent instructors. I suppose that we shall never reach the ideal state in the support of college professors set forth in the theory on which a call is extended to a minister in the Presbyterian Church. According to the book of discipline the call must read as follows,— "And that you may be free from wordly cares and avocations we hereby promise and oblige to pay.to you the sum of - during the time of your being and continuing the regular pastor of this church." It would take a good deal of money to set most of us free from " worldly cares and avocations."

The question of salary has to do with market values and yet is distinct from them. On the one hand the man who gives himself to the calling of a college teacher gives himself to a calling for which he has to make costly preparation, a calling which makes large social demands upon him, and a calling which stimulates his tastes, but which continually mocks him with its financial returns. On the other hand the college which invests in him to the extent of a life investment takes the risk of deterioration in personal enthusiasm or in some other form of personal efficiency. The position has for the average man the advantage and the disadvantage of the lack of competitive valuation. The exceptional man of market values always fares well enough anywhere. It would be a poor relief to the average professor in an American college to subject him to the competitive tests of the German professor, or to open to him the uncertain opportunity of the English don. We pay the price of dignity, permanency, and equality in low salaries. But the demand is no less real and urgent for an advance of salaries on some grade of instruction in every college. On the whole more money is earned by the faculty of a college than is received. This holds true when all considerations of a social and spiritual sort are taken at their full valuation.

The other demand of this human kind comes from students to whom the cost of a college education is well nigh prohibitive. It is not well to make the way through college too easy. A college education is worth a great deal of struggle and sacrifice. But in our endowed colleges we ought to have means to relieve, without loss to the college, all proper appeals for aid through scholarships. Whenever a deficit occurs in our colleges it is due in good part to the draft upon its funds in aid of men in the honorable struggle for an education. A college is a business corporation, but it has a soul. If administered ruthlessly or unfeelingly it violates the charter of its rights.

I have been asked to give in this paper a descriptive view of the administration of the modern college, to show the nature of the change from the old to the new. In attempting this object I have reached the limit of my paper. I simply refer in closing to a question which has recently been mooted—whether or not a change in the method of administering our colleges and universities, like that of turning over their management to the faculty, would be to their advantage. We can all see disadvantages in the present divided methods of administra-ion. But I doubt if it will ever be possible to change college administration at the root. The root is in the soil in which it grew. The American college, though the latest educational variety, is not necessarily the best. Its value lies in its adaptation to its work. It will probably do its best work under methods of administration which have proved themselves more effective in practice than promising in theory.

*The above address was given by President Tucker as one in a course of informal addresses topics connected with the executive management of corporate bodies, before the Wonolancet Club of Concord, N. H., December 7, 1905.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE practical workings of the preceptorial system

February 1906 -

Article

ArticlePRECEPTORIAL INSTRUCTION AT PRINCETON

February 1906 By Gordon Hall Gerould, '99 -

Article

ArticleTHE RHODES SCHOLARSHIPS

February 1906 By Julius Arthur Brown '02 -

Article

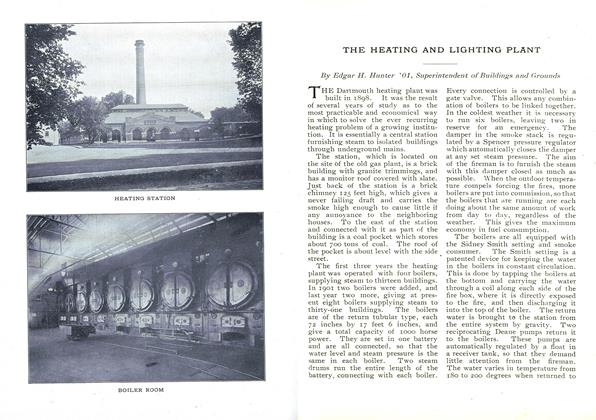

ArticleTHE HEATING AND LIGHTING PLANT

February 1906 By Edgar H. Hunter '01 -

Class Notes

Class NotesSECOND ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES.

February 1906 -

Article

ArticleWASHINGTON'S BIRTHDAY EXERCISES

February 1906

Article

-

Article

ArticleWILLIAM D. KNIGHT

AUGUST 1930 -

Article

Article'66 Secretary Dies

June 1931 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1943 -

Article

ArticleWith the Players

February 1937 By Alfred Reinman Jr. '37 -

Article

ArticleRES ANGUSTAE

May, 1922 By EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleTop Television Man

June 1950 By ROBERT R. RODGERS '42