ORIGIN AND MEANING OF THE REVISED RULES

[From the Outlook of November 24, 1906.]

THE present article is written essentially for the ignoramus. Knowing ones will elsewhere find far better and more scientific statements of. the case. By ignoramus, however, is not meant the person who does not know a punt from a pole vault, but that usual individual who, while interested in the great American game of football and fairly conversant with its general terminology, has no definite acquaintance with or understanding of the rules, new or old, and is hence in some doubt as to the effect of the changes long heralded and now in operation. That these changes may be more easily understood a resume of the theory and style of play in the old game should be given.

As now, a football team consisted of eleven men operating in a field 330x160 feet. Under the old rules they were placed with military precision; the heavy men, a "center" and two "guards," constituted the main bulwark for offense or defense — of necessity strong to hold against attack, powerful to tear down the fortress of the enemy. This center line supported two wings, each consisting of a "tackle'' and an "end," men again strong, but nimble as well, whose business was to prevent a flanking movement or to lead the way for an attack, according as conditions called for defensive or offensive measures. In the rear of the line thus constituted lay the flying squadron—the four backs, of full and fractional denomination. These, theoretically, were the players to carry the ball through breaches made in the enemy's line by attacks of the forward body. On the defense they' formed a secondary line to stop the enemy's progress should he pierce the center or skirt the wings.

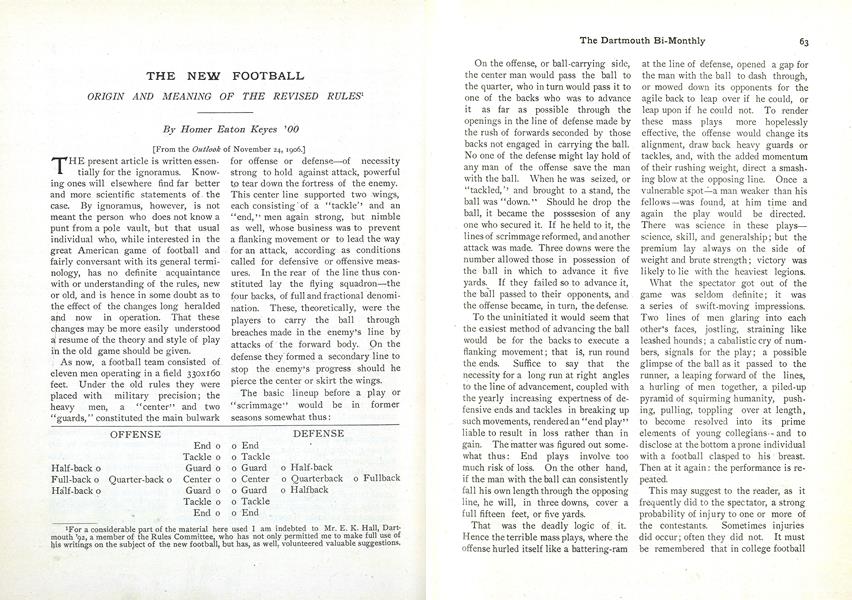

The basic lineup before a play or "scrimmage" would be in former seasons somewhat thus:

OFFENSE

End o Tackle Half-back o Guard o Full-back o Quarter-back o Center o Half-back o Guard o Tackle o End o

DEFENSE

o End o Tackle o Guard o Half-back o Center o Quarterback o Fullback o Guard o Halfback o Tackle o End

1For a considerable part of the material here used lam indebted to Mr. E. K. Hall, Dartmouth '92, a member of the Rules Committee, who has not only permitted me to make full use of bis writings on the subject of the new football, but has, as well, volunteered valuable suggestions,

On the offense, or ball-carrying side, the center man would pass the ball to the quarter, who in turn would pass it to one of the backs who was to advance it as far as possible through the openings in the line of defense made by the rush of forwards seconded by those backs not engaged in carrying the ball. No one of the defense might lay hold of any man of the offense save the man with the ball. When he was seized, or "tackled,'' and brought to a stand, the ball was "down." Should he drop the ball, it became the posssesion of any one who secured it. If he held to it, the lines of scrimmage reformed, and another attack was made. Three downs were the number allowed those in possession of the ball in which to advance it five yards.__ If they failed so to advance it, the ball passed to their opponents, and the offense became, in turn, the defense.

To the uninitiated it would seem that the easiest method of advancing the ball would be for the backs to execute a flanking movement; that is, run round the ends. Suffice to say that the necessity for a long run at right angles to the line of advancement, coupled with the yearly increasing expertness of defensive ends and tackles in breaking up such movements, rendered an "end play" liable to result in loss rather than in gain. The matter was figured out somewhat thus: End plays involve too much risk of loss. On the other hand, if the man with the ball can consistently fall his own length through the opposing line, he will, in three downs, cover a full fifteen feet, or five yards.

That was the deadly logic of it. Hence the terrible mass plays, where the offense hurled itself like a battering-ram at the line of defense, opened a gap for the man with the ball to dash through, or mowed down its opponents for the agile back to leap over if he could, or leap upon if he could not. To render these mass plays more hopelessly effective, the offense would change its alignment, draw back heavy guards or tackles, and, with the added momentum of their rushing weight, direct a smashing blow at the opposing line. Once a vulnerable spot—a man weaker than his fellows—was found, at him time and again the play would be directed. There was science in these playsscience, skill, and generalship; but the premium lay always on the side of weight and brute strength; victory was likely to lie with the heaviest legions.

What the spectator got out of the game was seldom definite; it was a series of swift-moving impressions. Two lines of men glaring into each other's faces, jostling, straining like leashed hounds; a cabalistic cry of numbers, signals for the play; a possible glimpse of the ball as it passed to the runner, a leaping forward of the lines, a hurling of men together, a piled-up pyramid of squirming humanity, pushing, pulling, toppling over at length, to become resolved into its prime elements of young collegians--and to disclose at the bottom a prone individual with a football clasped to his breast. Then at it again: the performance is repeated.

This may suggest to the reader, as it frequently did to the spectator, a strong probability of injury to one or more of the contestants. Sometimes injuries did occur; often they did not. It must be remembered that in college football the players undergo a process of selection and careful physical development that renders them far less liable to accident than might be expected. Serious hurts in college games have been comparatively rare; such things have occurred for the most part in secondary schools where the system of training is perforce less careful or the players too immature to profit by it; or they have resulted from impromptu contests whose participants had, almost with preparation, left office or factory for an afternoon on the "gridiron."

Be this as it may, the college game was undoubtedly rough; injuries even among properly trained men were, if not serious, frequent; canes, crutches, and bandages had become as important a part of football equipment as were canvas jackets and padded trousers. Perhaps worst of all is the number of men employed in each play, the violent physical contact, tended to rouse personal animosity in the players; while the close formations, the crowding quickness of mass attacks, gave exceptional opportunity for foul tactics and undetected infraction of the rules. Blows and kicks might be delivered, and even the keenest-eyed official be none the wiser. Since not all college men are gentlemen, since not all are true sportsmen, since to some winning at any price means success and losing means undiluted ignominy, blows and kicks were delivered, bad language flourished, and many a man was held who' did not have the ball. It is possible, too, that a part of the injuries inflicted were the result, not of accident, but of premeditated assault.

Further, it may be stated that certain spectators found the game incomprehensible and uninteresting.

On these accounts, during a period of years, a party of opposition had come into being. Protests against the style of play grew frequent; the sport was decried as brutal. As the friends of football remained silent, its detractors, more completely losing sight of its excellent features, became more vociferous in their denunciation. At the close of the s'eason of 1905 the general dissatisfaction reached its culmination. Newspapers compiled lists of the slain; wise professors, feeling that something was incumbent upon them as guides, philosophers, and friends of young manhood, rose up and pronounced anathema upon the game which, it is to be feared, some of them had never seen; enthusiastic faculties passed votes of total abolition—and later reconsidered them. The friends of football had failed to revise it when they could; they seemed unlikely now to have a chance of fulfilling their belated duty. That which had been denounced mainly upon physical grounds, for a time produced rather general hysterics among some of the critics of football.

In the midst of the tumult and the shouting, representatives of various colleges met together, viewed the situacion calmly, and came to the sensible conclusion that a form' of exercise which demanded, in high degree, skill, strength, daring, quickness of perception, loyalty, obedience, and self-control, was too fine a thing to be eliminated from the category of college sports. Might not the at present overshadowing features, roughness, bad feeling, brutality, and beefiness, be so mitigated as to allow the true ones to shine forth undimmed? It was worth trying.

Thereupon was chosen a special committee, which in due course, by subtle processes, became amalgamated with the old-time committee of seven, the fathers of the rules that were. The proposition then presented to these fourteen gentlemen was somewhat as follows: "The game should be made more open, mass plays should be abolished, unfair and unnecessarily rough plays should be eliminated, and provision should be made to insure a more uniform and stringent enforcement of the rules." It was a very simple statement of a complex and difficult task. While public, faculties, and trustees might not tolerate any failure to make the necessary changes; undergradutates, coaches, and players would not tolerate these changes should they interfere with the essential features of the time-honored game.

What the committee has done may be somewhat briefly outlined:

It has been seen that the logic of the mass play lay in the principle of about five feet to a down, or an aggregate of five yards in three downs. Destroy the logic of this play, and the play itself is destroyed. The logic was promptly destroyed by increasing the distance to be gained in three downs from five yards to ten. Further to establish the effectiveness of this rule, another rule was made whereby the side in possession of the ball must have at least six men on the forward or scrimmage line when the ball is put in play, and five of these should be center men—that is, the center, two guards, and two tackles. This provision eliminates the possibility of changing the offensive alignment by bringing back a heavy guard or tackle and using his added momentum in piercing or "bucking" the opposing line, except by temporary interchange of half-back and tackle, a device of dubious utility.* The only men now available for this purpose are the comparatively lighter ends and backs, who, it may be assumed, will scarcely be hurled so often directly at the defense when their strength must be reserved for longer gains around it.

The requirements thus weakening the offense were thoroughly logical, a matter of wise, indirect legislation. But the consequent problem that arose was how to render it possible for this weakened offense to make, in three downs, not five yards, but ten. An arbitrary rule correspondingly weakening the defense by scattering it in various parts of the field would have been direct and radical legislation—hence unwise. The matter must be automatically arranged by giving the offense new privileges calculated to gain distance by means of open formation. Such privileges were finally evolved.

The first of these relates to kicking. Under the old rules, when the side having the ball had failed to advance it in two downs, and the prospect was that another play would result in loss of the ball directly on the line of scrimmage, recourse was had to a long kick, which, while it delivered the ball to the opposing side, usually changed the scene of action to a safer distance down the field. No one of those on the kicking side could lay hands upon the ball until it had been touched by one of their opponents. As the rule now reads, any one may take possession of the ball as soon as it reaches the ground. It accordingly behooves the defense to keep sufficient men in the remote rear of their line to be certain of catching an unexpected punt. If they fail in this, there is constant danger that a short kick may elude the usual lone guard before the goal, and that the ball may be received by a speedy offensive end with a resultant gain of many yards. The double working of this rule is that it tends simultaneously to weaken the defense, by reducing the number of men in the line, and, by increasing the likelihood of a long gain, to encourage open formation on the part of the offense.

Another privilege is that of the forward pass. Heretofore the ball might pass from hand to hand so long as its direction was not toward the opponent's goal; infraction of the rule incurred a penalty. Now, however, once in each scrimmage, a player back of the main line may pass the ball towards the opponents' goal. The play requires wonderful quickness and accuracy on the part both of the passer and of him to whom the ball is passed; for there is no provision forbidding an opponent from doing the catching, whereas if the ball falls untouched to the ground it goes into the possession of the defense at the point from which it was first thrown. At the present writing, little more than the spectacular features of this play have been demonstrated. If any team has discovered how it may effectively be used for consistent gains, the knowledge is being withheld for a day of crisis. Like the previous rule, this one has a double action in its encouragement of open formations by the offense and in its automatic weakening in the defense by demanding that some part thereof delay hurling themselves into an attack which may, after all, pass over their heads.

In order still further to encourage open play by giving the runner carrying the ball a better chance to dodge his opponents, tackling below the knee has been legislated against. The runner's old-time straight-arm method of warding off his opponents may now be revived, for headlong dives at a player's feet are to be a thing of the past. Complementary to this rule is one which forbids the runner to jump over an opponent who obstructs his path. This jumping, or "hurdling," while comparatively innocuous in the open field, would never, theless render a fair tackle well-nigh impossible. In the mowed line of a mass play it had dangerous liabilities of sharp contact between runner's heels and opponent's face.

Such are the principal changes in the rules which will visibly alter the technic of football. Viewed in relation to their reason for being, they are not particularly startling or revolutionary. The committee had no desire for revolution; evolution along the lines of science and strategy was desired and has been secured.

But changes calculated to alter the style of play were not the only ones demanded. The ethics of the game was in the balance. How could fair and gentlemanlike conduct be assured and players be protected against assault and unnecessary injury? The obvious method of procedure was to increase the number of officials and to make penalties more severe. Both these things were done. An extra umpire is now called for; while in the matter of penalties, a contestant guilty of foul play is at once removed from the game and his side obliged to lose heavily in distance. Further, the committee made what proves to be an almost inspired provision.

The old method brought the opposing forces eye to eye, jowl to jowl. The brief period before the ball was put in play sufficed for much jockeying for advantageous position, for shoving, pushing, an indulgence in innumerable annoying devices calculated to arouse ill feeling and to lead to blows. In the flash and rush of the scrimmage a flying fist was not easily discernible; a player might have been goaded to reprisal for offenses committed during the interval.

To make things more visible to the officials, the two lines are now separated by the full length of the ball. And not only is the desired end accomplished, but, of greater importance than this, with the advent of a lane between the lines, the old-time petty warfare and wrangling have disappeared, and with them much of the bad blood and ill temper which have characterized the games of past years. The lane is called a "neutral zone;" the appellation is justified.

Another rule measurably affecting the ethics of the game is that relating to a fair catch—that is, the catching of a kicked ball by a player who does not intend to advance it by running. Such a player has always been immune from interference on the part of his opponents.

Formerly he declared his intention by digging his heel into the ground, a form of signal not always obvious to officials, and hence giving wide opportunities for infringement of the rules. The present provision requires that a player attempting to make a fair catch shall indicate his intention by raising his extended arm.

Thus the committee has endeavored to solve the problems, technical and ethical, which were presented to it. The opening of the present football season did not see the results of its labors received with unanimous enthusiasm by coaches, players, or studious spectators. Comfort may, however, be found in the fact that the new is always deplored by those who are satisfied with the old. There was gnashing of teeth, some years since, when the blood-thirsty "flying wedge" was relegated to the limbo of barbarities. But the game of football survived.

The pertinent question which arises at this point is whether or not the new rules will accomplish what was expected of them. Has mass play been abolished ? is muckerism a thing of the past ? are injuries no longer to occur?

Mass play has been abolished; but its terrible force has been destroyed, and its availability between equally matched teams has been reduced to a minimum. It will be used where short gains are needed, but the team which now depends upon the weight of its formations will soon find itself unequal to its task. Skill, quickness, resourcefulness, have already been shown of greater avail than mere beef and brawn; already coaches who relied upon the superiority of the old-time material to justify them in clinging to old-time tactics have seen their teams go down m defeat before lighter and nimbler rivals.

Muckerism is not necessarily a thing of the past. Rowdies cannot be legislated into gentlemen. The committee has done its best to make decency the best policy. For the rest, dependence must be had upon the courageous honesty of officials in enforcing penalties, and upon the sentiment of college men and the general public in giving support to such enforcement. When a college body feels itself disgraced, not abused and imposed upon, by the exposure and punishment of unsportsmanlike conduct on the part of one of its representatives, then, and not till then, will muckerism cease to be.

Injuries will never be completely eliminated from football. It will never be a game for children or for untrained men. But the weakening of mass plays, the premium placed upon formation, the provisions against fouls, and the wise rule which limits the number of rests allowed, and hence compels the overtired player to retire from the field and be replaced by one in full vigor, all tend to reduce the likelihood of such injuries as will counter-balance the good in a sport which, at its best, develops manhood, courage, self-reliance and self-control more than any other one agency of college life.

When a tackle is unusually nimble and swift, it may occasionally happen that he will be brought five yards behind the offensive line, thereby replacing, and being replaced by one of the half-backs.The formation thus arranged may Prove available for short, sure gains through centre. But the distance to be covered at high speed is so great that it quickly exhausts a heavy man and hence reduces his effectiveness in his legitimate position.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1906 -

Article

ArticleMEMORANDUM OF THE TRUSTEES ON THE RHODES SCHOLARSHIPS IN THE UNITED STATES

December 1906 -

Article

ArticleIN other columns the BI-MONTHLY

December 1906 -

Article

ArticleHONEST WILL LEGGE

December 1906 By Marvin D. Bisbee ' 71 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1866

December 1906 By Henry Whittemore -

Article

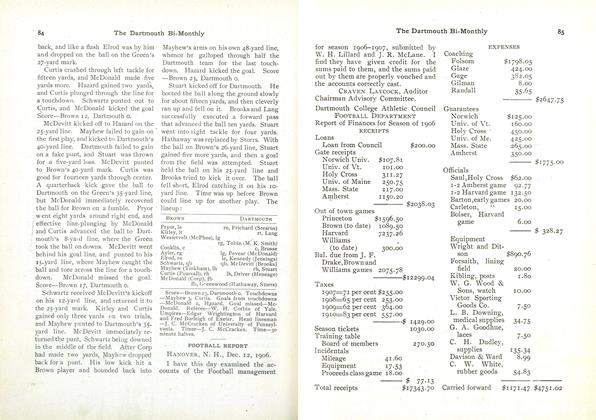

ArticleFOOTBALL REPORT

December 1906

Homer Eaton Keyes '00

-

Article

ArticleNo Award for Prize Song

February, 1911 By EDWARD K. WOODWORTH '97, HOMER EATON KEYES '00, HARRY R. WELLMAN, 1 more ... -

Article

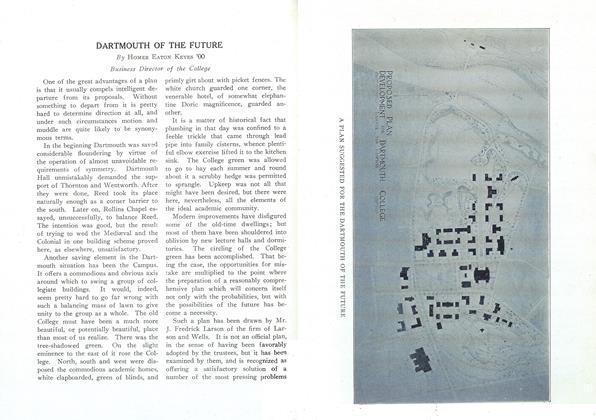

ArticleDARTMOUTH OF THE FUTURE

July 1920 By HOMER EATON KEYES '00 -

Article

ArticlePURE DEMOCRACY AND THE COLLEGES

January 1922 By HOMER EATON KEYES '00 -

Article

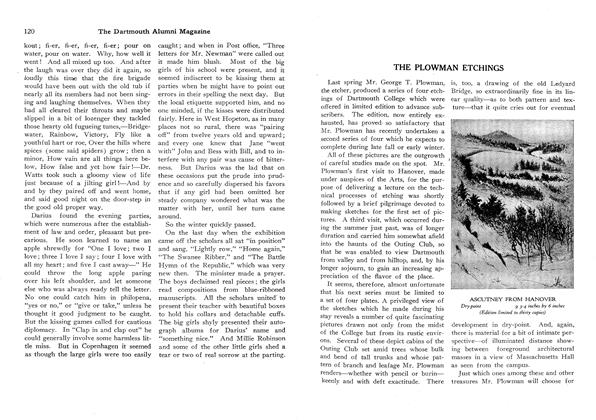

ArticleTHE PLOWMAN ETCHINGS

December, 1922 By HOMER EATON KEYES '00 -

Article

ArticleA Tribute to Natt W. Emerson, Practical Idealist

March 1936 By Homer Eaton Keyes '00