As personal representative of President Eisenhower with the rank of Special Ambassador, a Dartmouth man has witnessed African history in two countries. He is Robert P. Burroughs '21, and the countries are Cameroun and Liberia.

It was an exciting experience from beginning to end. About December 10 the telephone rang in the offices of R. P. Burroughs Inc., actuarial consultants, Manchester, N. H., and the White House was calling to know if Mr. Burroughs would accept the appointment. It would mean elaborate briefing in Washington, some 13,400 miles of flying in The Independence, the DC6B first used by President Truman and then by President Eisenhower, and four days in Cameroun and another four in Liberia. It would be hot. Even in January the mercury would go up to 105 degrees.

Mrs. Burroughs got a thrill also. She was invited, the only woman except for Mrs. Henry Cabot Lodge. The U.S. party also included Mr. Lodge, head of the U. S. Delegation; Joseph Satterthwaite, Assistant Secretary of State for Africa; Mason Sears, U. S. Member of the Trusteeship Council of the United Nations; Major General Benjamin O. Davis Jr., USAF; Representative Steven B. Derounian of New York; and Representative Charles C. Diggs of Michigan. It did not take Mrs. Burroughs long to say yes.

All Africa was in a state of excitement. Cameroun was the first of the trusteeship territories under the United Nations to become independent, and naturally the hopes of delegates from other African territories rose to fever pitch.

In Africa Bob Burroughs met delegations from almost every country, many of them colorful in their official and native costumes. He shook hands with men from Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and other African countries, not to mention Asiatic. Some wore beautiful hand-woven robes with intricate patterns; some, handsome tarbooshes, brimless caps of felt or cloth shaped like a truncated cone; some men sparkled with rich jewels, adornments reserved only for historic occasions. Some of them proved to be intelligent, sophisticated, well informed: fascinating dinner companions.

In both Cameroun and Liberia, Bob Burroughs found that when one gets back of cities, like Yaounde and Douala, into villages, the houses are only mud huts with grassthatched roofs in which people live with little education and less clothing. He learned, however, from missionaries and officials that many of these simple people have astonishing quickness and perceptivity. A city and an education may transform a boy so illiterate as to seem dull into a young man capable of thinking for himself in adult and expressive fashion. Indeed no less a person than Prime Minister Ahidjo came from such a mud hut, and the schooling and intellectual disciplines he enjoyed in Dakar and Paris turned him into a statesman with considerable stature.

The problems of Cameroun are still enormously difficult. Prime Minister Ahidjo is the first to admit that despite the limitless enthusiasm his countrymen have about independence, he and they will need guidance and help for years to come, but the help and guidance should not be forced or given unasked. They want to be able to seek them on their own initiative.

How far away the goal of complete independence, peace, and prosperity is Bob Burroughs himself found out when he was in Africa. The Bamelike, a terrorist organization backing a man named Moumie to be prime minister, killed a considerable number of persons and indeed even chopped up a few with machetes because the dead men had been so stupid as to fail to follow the terrorists' advice.

Though such lawlessness suggests darkest Africa with jungle warfare, the American Special Ambassador is encouraged about the future. The aggressive sense of inferiority in the people of Cameroun means only that they wish to work out their own destinies. The white men's burden is an out-of-date slogan. Early investigations suggest that Cameroun and Liberia have rich natural resources. President Tubman of Liberia, whose inauguration the Americans attended, and indeed delegates from Nigeria, Guinea, and all the African countries kept stressing that the leaders in Africa are intensely eager and earnest about the roles they feel they must play in a civilized world freed at long last from the evils of colonialism.

At the celebrations in Liberia and Cameroun the Russians not only outnumbered the Americans but also all other nationals. They had 26 men. They lived up to their high ideals about the people's democracy and refused to wear dress clothes for special occasions. The Africans were not flattered. The Russians, unwilling to run the risk of contamination incurred by rubbing shoulders with Europeans and Americans, kept to themselves and hoped to create a favorable impression by sheer force of numbers. If they could speak a language other than Russian, they gave no indications of their linguistic achievements. The Africans whose sincere hope it is to be able to live in peaceful and understanding cooperation with the rest of the world were somewhat less than happy with Russian behavior.

Everyone in the American delegation, aware of the spread of education in Liberia and Cameroun, returned to the United States with a firm conviction that in future years the countries of Africa constitute a world force almost impossible to reckon accurately at the present time. Should they go communist, the loss to the free world would be so disastrous as to be catastrophic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor Jesup's Herbarium

March 1960 By JAMES P. POOLE -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60 -

Feature

FeatureAre Marriage and College Compatible?

March 1960 By MARGARET MEAD -

Feature

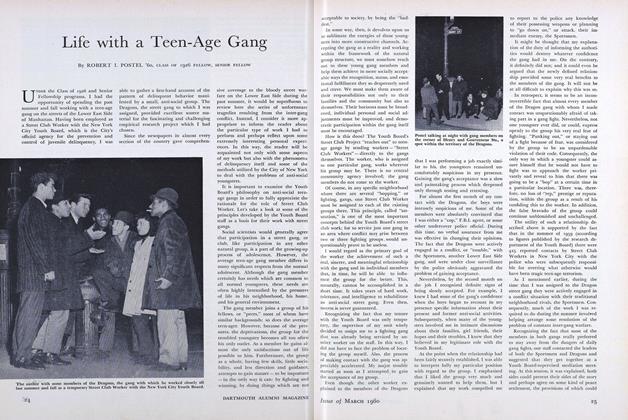

FeatureLife with a Teen-Age Gang

March 1960 By ROBERT I. POSTEL '60 -

Article

ArticleThe Mission of Liberal Learning

March 1960 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, ROBERT FISH