The following editorial appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript upon the announcement of the Senior Fellowships at Dartmouth:

A senior in college who has no required classes, who takes no examinations and pays no tuition fee! From September until June a student wholly free to study "in whatever manner and direction he himself may choose!"

Such is the charter of freedom which Dartmouth College has decided to confer upon a specially qualified group of its students. Hereafter at Hanover, according to a vote of the trustees published in our news columns today, five men—possibly more, perhaps less —will be chosen annually, at the the end of their junior year, to receive rank as "senior fellows." These men must spend their fourth year in residence at Dartmouth, but during that time, to the day when their degrees are awarded, they will be subject to no superimposed requirements whatsoever.

Here is an award of fellowship which would have been quite impossible of adoption ten or more years ago in any college of this land. The broad, underlying changes in educational practice, which are necessary to the success of such a plan, had not yet come to pass. A few college presidents had begun to give thought to the question, "What can we do, and what should we do, to provide the better students in the undergraduate body special opportunity to use and develop their powers to a full measure of excellence?" But little was done before the war to answer this inquiry. Students of high standing were, of course, always welcomed and congratulated, especially at the time of Commencement, but academic arrangements expressly designed to serve their welfare during the four-year course itself were, at most of our colleges, conspicuously non-existent. It is not too much to say that in general a negative ideal prevailed. All the heavy artillery of the dean's office was trained upon a single objective—the task of preventing some of the poorer students from "getting by." That is to say, the self-respect of the college authorities was chiefly satisfied by making sure that men who really deserved to be "flunked out" were duly and bravely dismissed.

Since the war—with important beginnings in a few colleges before the war—a sweeping change has occurred. On the one hand, the great increase in 'the number of boys and girls seeking entrance to college made it not only necessary, but easily possible, for many institutions to enforce more rigorous standards of admission than they had ever maintained before. The mere business of excluding poorly qualified students, and of discharging students who neglected their work after admission, became a commonplace of the academic year in most of our colleges, and as such rather lost its savor. No college could continue to feel that it was showing any particular virtue or courage solely by maintaining a high percentage of "flunk-outs."

On the other hand, positive provision for the welfare of the more competent and industrious students began to be made in abundance. "Honors courses," for the benefit of juniors and seniors who had shown good scholarship in their freshman and sophomore years, were established in many colleges. Special privileges were accorded, as to the men on the "dean's list" at Harvard. At Dartmouth the group of students doing "honors' work" has had a steady and important growth. Today between 20 and 30 per cent of the two upper classes enjoy that rank. And these men do practically all of their work in their chosen "major subject" on the basis of conference and consultation with professors and instructors. Classroom attendance and the usual machinery of rules, "hour-test" and involuntary routine are thus already reduced to a minimum for Dartmouth's large present group of "honors" men, from among whom the new Senior Fellows no doubt will be chosen.

So the way has been prepared at Dartmouth for the establishment in 1929 of a plan which in 1909 would have been wholly impossible and impractical of adoption at any American college. It is, in our opinion, a great and significant step of progress which President Ernest Martin Hopkins has taken. The Senior Fellows, says a distinguished alumnus, "will serve as a constant reminder to every undergraduate and every member of the faculty that the college regards the free and untrammeled pursuit of the inteltellectual life as the highest good, an ideal which has somehow been mislaid or forgotten in many American institutions of learning. They will also suggest to the undergraduate that the college is ready and willing to regard him as a responsible human being and not as a child." We believe this an important objective in higher education, one destined to be increasingly the main end and aim of American colleges.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Survey of Undergraduate Activities

May 1929 By Carl B. Spaeth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

May 1929 By H. Phillip Patey -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

May 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

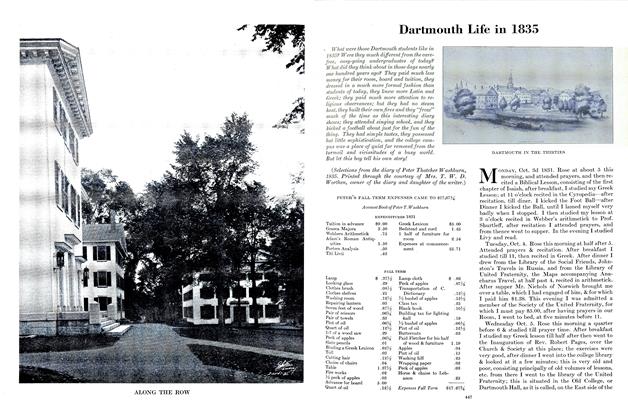

ArticleDartmouth Life in 1835

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1929 By Arthur P. Allen