During the college year 1907-1908, the members of the faculty in the division of social sciences recommended to the general faculty the establishment of a system of faculty advisors. As the suggestion did not meet with a sufficient degree of approval, the project was dropped for the time being. Early in the administration of Dr. Nichols, the proposal was revived. President Nichols had himself come into contact with a similar system at Columbia University and was in favor of its initiation at Dartmouth. Many members of the faculty, also, were impressed with the fact that the great growth of the college in numbers was making imperative some machinery by which the individual student could come into personal touch with the instructing force. With the cooperation of the president, plans were discussed at a general faculty dinner, through the tranquillising influence of which a degree of unanimity and enthusiasm were aroused for an advisor system.

Further discussion, although not assuaged by coffee and cigars, resulted in the construction and assembling of the necessary machinery. The Board of Student Advisors—composed of the greater part of the faculty,—an Executive Committee, and a Secretary, were all that were deemed necessary. From the beginning it was found advisable to make service in the Board entirely voluntary and to restrict it to members of the faculty of at least one year's standing. The Board has, therefore, from the outset been an entirely unofficial body and its work has been founded solely on the spirit of helpfulness. Professor G. F. Hull acted as Secretary from 1910 -1915, with his usual conscientiousness and efficiency. It was largely due to him that the machinery was properly put together and the roughnesses worn away.

The activities of the present college year may serve to typify the spirit and purposes of the organization. On August 20, 1915, or as soon thereafter as his credits were filed with the Dean and his room deposit was. paid, every incoming freshman received a copy of the following letter:

DEAR SIR:

In order that every student entering Dartmouth College may feel that there is a member of the faculty to whom he has an especial right to .go for information and friendly counsel, each member of the freshman class will be assigned to some member of the faculty who will act as his advisor during freshman and sophomore years, and during the entire course if the student desires. The relation between the student and his faculty advisor is entirely unofficial and friendly. The student will feel that he can go to his faculty advisor, on terms. of mutual confidence, for counsel on questions concerning the curriculum, personal difficulties, or any of the varied problems certain to arise in getting adjusted in the new environment.

In order to assist the Secretary of the Executive Board in assigning advisors, will you kindly read with care the enclosed sheet of questions, fill in the blanks, and mail to Professor Charles R. Lingley, Hanover, N. H., at the earliest possible moment. An early reply will enable the secretary to send you the name and address of your advisor before you leave for Hanover.

Enclosed with the letter was a list of the members of the Board of Advisors, together with a brief questionnaire which was designed to enable the secretary to assign students to advisors who would, in as many cases as possible, be congenial. The more significant questions follow:

Mention the names of any members of the Board of Student Advisors with whom you have any acquaintance or with whom you would have any common interests, (e. g., acquaintance with alumni.) If you wish anyone of them to act as your advisor, write explaining you reasons.

In what studies have you had an especial interest ?

What have been your chief interests outside of studies?

What profession or life work do you intend to enter?

Whenever possible, students who requested specific members of the faculty were assigned to them. Otherwise, assignments were made on the basis of common interests inside or outside of the class-room, as indicated by the student's answers to the questionnaire. By these means advisors were appointed for a very large fraction of the Class of 1919 before College opened, and in many cases some correspondence between the advisor and the student was entered into. Many advisors held open house for their advisees on the afternoon or evening of the first Sunday of the college year,—that dread, first milestone on the road through Home-sickness Hollow to Maturity. In, these and in other ways, seventy-two per cent of the new men met their advisors within two weeks of the opening of college.

It is impossible to relate in detail the multifarious ways in which students and advisors have been mutually helpful. An investigation among the members of the Class of 1919 in which three hundred and thirty students wrote impressions of the system shows that almost every difficulty which the new student can meet, from how to use skis and how to study, to how to get a degree and how to earn money, were subjects for helpful counsel by the advisors. In a few cases, students met crises in life when an advisor was invaluable; in one, the student confesses that the advisor "made me feel that I belonged here"; and again, the advisor "has shown a sympathetic interest in me" and "helped me from becoming discouraged."

As in the case of most Dartmouth activities, the alumni can exercise a helpful influence Next summer, when the Secretary of the Board gets into touch with the Class of 1920, he will send out a questionnaire somewhat similar to that of last year, but at the head of the list of questions will be the advice: "Before filling in the blanks, read with care the explanatory letter sent here-with and discuss the subject with parents and with alumni who may be able to guide you in making a wise choice." Many alumni will find here opportunity to aid new students in making a judicious choice of advisor. They can, at the same time, urge upon the freshman the wisdom of meeting the advances of his advisor in good faith.

There are, of course, critics of the advisor system. Objections most often come from students who chance not to find a congenial advisor or from those who happen not to feel the need of the counsel of an older man. But even in these cases, the critic generally urges some alteration in the system or some substitute for it,-never the entire lition of the attempt to perform the services which are the goal of the present scheme. Not infrequently hostile criticism of the system springs from expecting too much of it. The relation between advisor and student cannot be one of very great intimacy. The instructor is too busy and the student should normally be finding close friends among his fellows, even assuming that great intimacy would be desirable. It is not, again, to be expected that all men will seek or even need the counsel which the advisor can give. Many of them do not meet serious exigencies or feel the need of advice beyond what they can procure from student acquaintances. And yet again, it is not surprising that frequently students .consult instructors other than their advisors. Members of the Board sometimes exclaim in. rueful puzzlement, "The undergraduates whom I advise are not my advisees,—mine go to somebody else." While it is certainly to be hoped that students will go to their own advisors most often, the ultimate goal is the establishment of friendly relations between instructor and student. If the boys get the habit of consulting older men about their intellectual, physical and moral problems, the purpose will have been accomplished. The machinery is made for product, not the product for machinery!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

April 1916 By Gray Knapp '12 -

Article

ArticleOf late years no Boston dinner of Dartmouth

April 1916 -

Article

ArticleCARNIVAL ELICITS COMMENT

April 1916 -

Article

ArticleTHE WORK OF THE FRESHMAN CLASS OFFICER

April 1916 By Frank A. Updyke -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1916 By Sturgis Pishon -

Article

ArticleMILITARY TRAINING CAMPS

April 1916

Charles R. Lingley

-

Books

BooksThe Life of Thomas Brackett Reed

By CHARLES R. LINGLEY -

Article

ArticleSALMON P. CHASE, UNDERGRADUATE AND PEDAGOGUE

October 1919 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

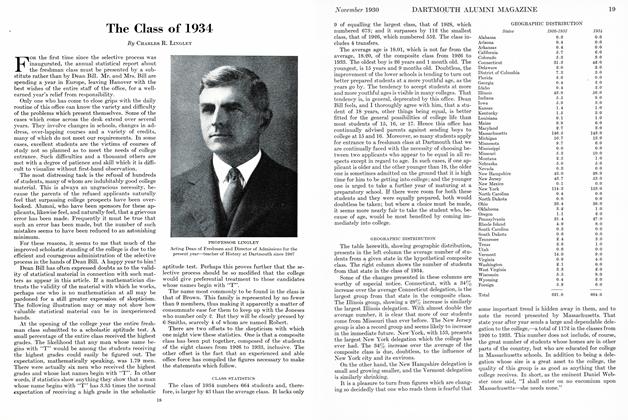

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November, 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Books

BooksWILLIAM HOWARD TAFT

January, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleSome Misapprehensions in Regard to the Selective Process

February, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleRichardson's New History of the College*

MAY 1932 By Charles R. Lingley