A LUMNI and all others who are interested in the origin and growth of Dartmouth College will find these volumes uncommonly enjoyable. Moreover, if read widely by those who have any functional relationship to the College, they would provide an excellent common body of information for use in the discussion of present and future problems.

As Professor Richardson explains in his Preface, the writing of these volumes was undertaken at the request of President Hopkins and in the expectation of producing an account of the College that might be of interest to the general reader. The standard history written by Mr. Frederick Chase and Professor John K. Lord is roughly twice as long as "L.B.'s." It is encyclopaedic in its wealth of detail. It will surely remain the most authoritative book of reference. But it does not present a story of sufficient brevity and clarity to satisfy any except the most earnest of readers.

Much attention has obviously been paid to the format of Professor Richardson's book. The type-page, in particular, is wholly agreeable—attractive to look upon, and comfortable to read. Volume One closes with the early years of Nathan Lord's administration (1828-1863); Volume Two carries on to the close of Dr. Tucker's administration, with a concluding chapter on "The College in Recent Years."

Both in general plan and in the details of sentence structure and diction, the volumes are characterized by lucidity. Details never becloud the main issue. Perhaps no better proof of this statement can be given than the assertion (a boastful one, I admit) that there were times while I was reading Professor Richardson's account of the Dresden episode when I almost felt as if I understood it. I never succeeded in getting that far before. Particularly attractive passages are such graphic bits as that on page 210 concerning the beginning and the end of old Dartmouth Hall, and the appraisal of Dr. Tucker on pp. 668 and following.

Much space is devoted necessarily to the history of the tangible College—to the sale and purchase of land; to the construction, moving and demolishing of buildings; and to the slow and painful process of finding money, struggling with deficits and making both ends come as near to meeting as human energy and ingenuity could make them. There is the budget for 1814, for example (p. 237). This, one might remind himself, was forty-five years after the College was chartered. On the expense side the expected outlay was $4,852.59. It included the salary of the President, the entire faculty, the treasurer, the inspector of buildings—everything.

More diverting than the material aspects of thegrowth of the College are the curriculum—standing like Gibraltar for a century; the slowly widening distribution of the sources from which the student body came; the social origins of the undergraduates; expenses, scholastic standards, admission standards, the day's routine—and discipline, more discipline and yet more. Before the reader, indomitable Eleazar Wheelock walks again; John Wheelock—the early part of his administration evaluated more highly than has been the case before; the first faculty, Smith, Ripley and Wood-ward; the overpowering Webster; Francis Brown, taken from the College too early; Nathan Lord, with his green spectacles, suspending his own son, exhibiting his skill as a skater to a wondering throng when well over seventy years of age; Samuel C. Bartlett, that astonishing combination of characteristics; William J. Tucker, with his vision and quiet masterfulness; and an army of others.

This reviewer congratulates Professor Richardson on many accounts, and among them the possession of a sense of humor. The salty remarks which adorn some of these pages are subtle enough to make the reader feel self-satisfied to discover them; they are not so deep as to require excavation. There is, for example, this story of President Lord (p. 473): "On one occasion, however, after much trouble with 'horning' episodes, the college was confronted, upon approaching the chapel, with the huge image of a negro, carrying under his arm a horn six feet in length, suspended by the neck over the face of the college clock. Whereupon the president announced, 'Gentlemen, I observe that one of the characters who have disturbed the quiet of our village of late has been suspended, and I would suggest that his associates may come to the same condition unless they speedily mend their ways.'" President Bartlett's command of innuendo was no less timely. On one occasion "when an outhouse had been brought from a distance and deposited near the chapel door, the president spoke in reproving terms of those who had transported to a position so near the college their own ancestral halls" (p. 593). Or yet again: Near the close of the year 1886-87 the faculty voted that two athletic juniors should "be excused for the remainder of the term to play with an amateur team for the purpose of earning money." (p. 643.) And still again on pp. 105, 135, 139, 224, 251, 256, 265 and 416.

It would be unnecessary to summarize Professor Richardson's account of the historical development of the College for the readers of the ALTJMNI MAGAZINE. Perhaps the mention of a few items in the story may better serve the purpose of indicating what is to be found in these two volumes.

Reliable Benjamin Pomeroy, member of the first Board of Trustees, making his toilsome way up from Connecticut for meeting after meeting, must be still in the minds of the Board if their constant attendance is a criterion.

lam inclined to disagree with a statement on page 241. In speaking of the poverty of the students entering College in the early nineteenth century, Professor Richardson remarks: "By the mere force of circumstances a 'selective process' was in operation which probably has never been equalled in efficiency in the history of the college." It seems likely that in general the student whose family has to make great sacrifices in order to give him an education is more likely to take full advantage of his opportunity. And yet the number of exceptions to this rule, and the number of boys from more prosperous families who do exceedingly well is too great to justify L.B.'s assertion.

On p. 397 is quoted a lament of President Lord's which this reviewer plans to re-read during the next period of grading final examinations: "Me miserum! when shall I rest from this sorry labor? For myself I could not perform it. But for the College and the great interests with which it is connected, it is well to suffer. Especially in view of enlightment and success which I believe God will send."

President Lord inaugurated a "reform" which has no little interest (p. 441 f.f.). It was his belief that "ambition and emulation are selfish principles, that they are consequently immoral and ought not to be appealed to in a private or public discipline, that though they exist naturally in man, they are not of Divine origin, but the product and evidence of an apostate and disordered mind; that the work of education should not be to stimulate and train, but, so far as possible, to eradicate them, and that education then only is moral or answers its proper design when it prevails over them and substitutes for them the disinterested virtue of Jesus Christ." In 1835 the giving of honors and distinctions was accordingly abandoned. For a time it seemed that a new source of inspiration had been discovered. The College during the following years prospered uncommonly. The President thereupon warned the trustees "that the unusual flocking of undergraduates to Dartmouth, at the expense of other institutions, could not be expected to continue, as these sister colleges would soon discover the secret and adopt the new principle as their own." (p. 443.) Apparently, however, President Lord was arguing post hoc, ergo •propter hoc. During the early forties, student registration declined as rapidly as it had arisen. Disagreement about the efficacy of the new plan cropped out again and again. And upon the retirement of President Lord the College went back to prizes, distinctions and honors. Another revolution of the wheel had taken place.

Certain statistics (p. 461) do damage to the theory that past days were the "good, old times." It appears that in 1828-29 there were fifty-one faculty meetings, and in 1832-33, sixty-eight.

The volumes close with exactly the right note (p. 801). It is a quotation from Professor Richardson's Study of the LiberalCollege. "Our aim may therefore be stated as the stimulation of those gifts of intellect with which nature has endowed the student so that he becomes, first, a better companion to himself through life, and, second, a more efficient force in his contacts with his fellow men." Succeeding generations will indeed do well if they can add anything to this as the aim of a liberal college.

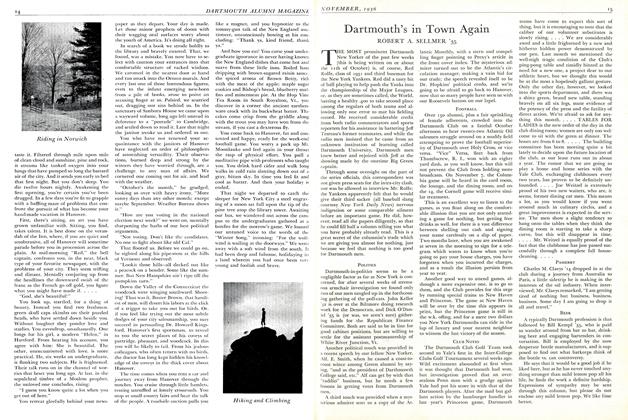

LEON BURR RICHARDSON Author of the new narrative history of Dartmouth

*Published by Dartmouth College Publications, Hanover, N. H., 1932, two vols., 854 pp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

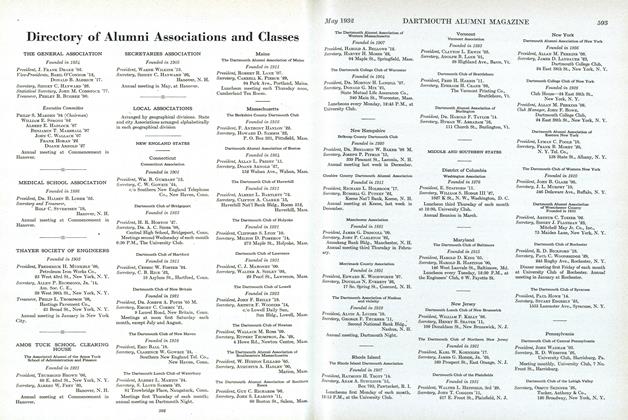

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D.

Charles R. Lingley

-

Books

BooksThe Life of Thomas Brackett Reed

By CHARLES R. LINGLEY -

Article

ArticleTHE SPIRIT AND MECHANISM OF THE ADVISOR SYSTEM

April 1916 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleSALMON P. CHASE, UNDERGRADUATE AND PEDAGOGUE

October 1919 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

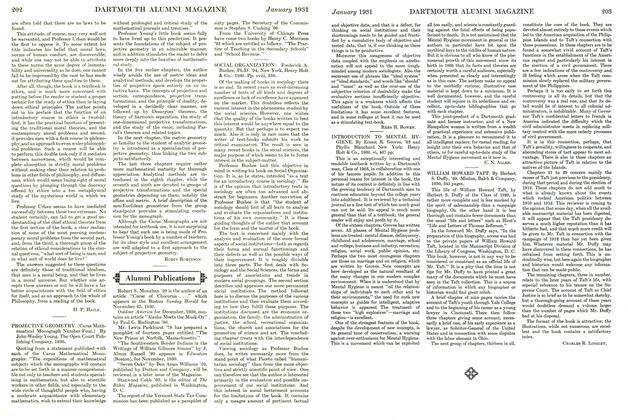

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November, 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Books

BooksWILLIAM HOWARD TAFT

January, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleSome Misapprehensions in Regard to the Selective Process

February, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley

Article

-

Article

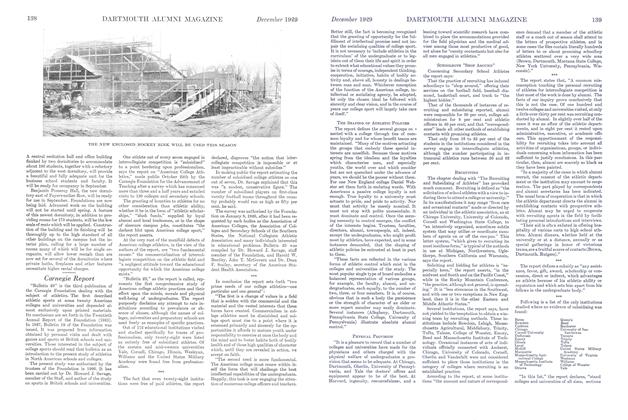

ArticleCarnegie Report

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleOur Own Class Notes 19-

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleTrustee Meeting

May 1945 -

Article

ArticleGIVE A ROUSE TO REUNERS

SEPTEMBER 1997 -

Article

ArticleWYMAN TAVERN, THE INN AT KEENE, NEW HAMPSHIRE IN WHICH WAS HELD THE FIRST MEETING OF THE TRUSTEES OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1920 By Elgin A. Jones '74 -

Article

ArticlePOLITICS

November 1936 By ROBERT A. SELLMER '35