DURING the course of a year, the office of the Director of Admissions hears many unfounded rumors in regard to some aspects of the operation of the Selective Process. Many of these misapprehensions are, at first sight, somewhat astonishing. Perhaps it would be more astonishing, however, if so complicated a procedure as the Selective Process should be understood accurately on all sides and by all people who come into contact with it. Such a full understanding would be miraculous indeed.

Perhaps it may help to clarify the existing situation to mention some of the most common misapprehensions and state, as briefly as may be, the practice in the office of the Director of Admissions.

(1) That a student cannot enter Dartmouth College unless he stands in the highest quarter of his secondary school classes.

In brief, it should be said that admission to Dartmouth College has not been restricted to students standing in the highest quarter of their preparatory school classes, is not now so restricted, and, so far as can be prophesied, will never be restricted in this way.

It is, however, fair to say that entrance to Dartmouth College is highly competitive, and that the better any applicant stands in his school courses, the better his chances for selection. In the present Freshman class, nearly 57 per cent of the 664 members did actually enter by "honor certificate,"—that is, they were in the highest quarter of their school classes. The remaining 43 per cent entered by regular certificate or by examination. Perhaps these figures fairly portray the chances which a student would have of being selected if he did not stand in the honor certificate group.

(2) That there is a specific quota for some states, sections, towns, or schools.

We frequently receive letters from prospective applicants indicating a misapprehension that they cannot apply for admission to Dartmouth College because somebody else in the same preparatory school has already applied. The fact that another student, or another ten students, or another twenty students, had applied from that school or town or section, should not deter anybody from presenting his application.

It should be said, however, that it may becomenecessary at any time to place a quota on some metropolitan areas. At the present time it would probably be possible to make up a freshman class in large measure from applicants living in four or five metropolitan areas like Boston, New York, Chicago, and others. Obviously it would be unfortunate if the clientele of the college were restricted to a few, or even to a considerable number of urban areas. It may at any moment, therefore, be necessary to limit the number of applicants to be selected from these urban districts.

It might conceivably be necessary, likewise, to limit the number from a given school, if the numbers from any given school should grow to such an extent as largely to dominate any given class. That time has not arrived.

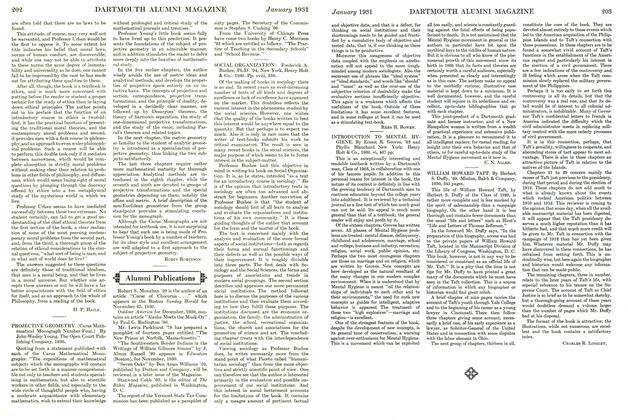

PREFERRED GROUPS VERY SMALL (3) That the preferred groups—that is, alumni sons and applicants from the South, the West, and New Hampshire—fill up the Freshman Class so that applicants not in these groups are substantially handicapped in applying for entrance. In this case, statistics tell the story accurately and quickly: Twenty members of the present Freshman Class of 664 members come from south of the Ohio and Potomac. Forty-one come from west of the Mississippi. Twenty-eight come from New Hampshire. Fifty-five are sons of alumni (of whom 7 are in one or another of the above groups).

Six students are from foreign countries. In other words, 143 members of the class fall into what may be termed "preferred groups." Perhaps it is not necessary to reiterate the fact that these students must all have the requirements for entrance (that is, fifteen units of credit properly distributed, or an honor certificate).

(4) That candidates who have filed their applications early have priority over later applicants.

The answer to this is that priority of application has no effect up to April 1, except when it comes to making a choice of rooms. All applications which are received previous to making selections in April for the next class are thrown into the pool and the best ones, so far as we can judge, are taken out and compose the next entering class. Once the selection has been made, however, applications received thereafter are distinctly handicapped. Students who apply after April 1 face the fact that the next class has been practically picked, and that they have almost no chance of selection unless they have some very unusual qualifications.

After a class is selected, the men chosen receive from the Bursar's office information in regard to choice of rooms, and at this time the earlier applicants have a slight advantage.

NO PREFERENCE TO PRIVATE SCHOOLS (5) That the private school (public school) candidate has a better chance of entrance than a public school (private school) applicant.

The answer to these misapprehensions is that the better a student's standing during four years of classroom work, the better his chance of being selected for admission to Dartmouth College. If two students present scholarship records on an absolute equality and if one comes from a private school and the other comes from a public school, and if one of these has to be accepted and the other rejected, the decision is not made on the public school vs. private school basis. Of course, if one comes from an excellent public school and the other from an inferior private school, or the reverse, it is desirable to pick the student who comes from the higher grade school. But only in such a contingency would the question of public vs. private school come into operation.

NEITHER ATTRACTS NOR BARS ATHLETES (6) That the Selective Process so operates as to bring athletic students into Dartmouth College.

Every college presents to its student body two types of development—one is the strictly classroom opportunity, and the other is the extra-curricular opportunity. The well-rounded college student will, surely, have taken advantage of both of these fields of development. At the present time it cannot be stated too frequently that extra-curricular development must always be based on the intellectual activities of the classroom, the laboratory, the lecture room, and the library. Unless the activity of the college is founded on these intellectual opportunities, extra-curricular activities turn the college into a club, and from a club it disintegrates and eventually disappears. Hence the Director of Admissions must continually select students for entrance to Dartmouth College on the basis of the adequacy of their scholastic preparation, their demonstrated ability in school to take advantage of the offerings of the college, and so far as may be judged, their desire to take advantage of these opportunities. This always has been, is now, and undoubtedly will continue to be, the central point in the policy of admissions. If, however, an applicant has these intellectual capacities and if these capacities are supplemented by talent in music, debating, athletics, or any other field of interest, surely this applicant is better college material than an applicant whose intellectual capacities are not so supplemented. (7) That the Selective Process so operates as to keep athletic applicants out of college.

There is, in some quarters, the misapprehension that the Selective Process admits no athletes and that the college is in danger of becoming filled, as the expression is, with "be-spectacled Phi Betes." This danger, if it exists, is not likely to be a source of great concern to most colleges for some time yet in the future. The fear that a selective process will be operated on scholarship alone, narrowly so considered, is a fear that is scarcely well founded. It is, perhaps, quite natural that people who fear the operations of the Selective Process on this ground do not frequently enough debate the question out with people who fear the operation of the Selective Process on the ground of the misapprehension mentioned in (6).

After all, as has been often and wisely said, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. If this be so, it may be worth while to recapitulate in a few sentences some of the developments of the college in recent years.

HIGHER STANDARDS On the extra-curricular side, it seems demonstrable that the college has been greatly enriched during the last five or ten years by the students who have entered as a result of the Selective Process. Our Glee Clubs have probably set higher standards of artistic performance than Dartmouth has hitherto known. Probably most of the athletic teams will bear comparison with any similar period of earlier times. Undoubtedly there has been more reserve material for many teams and many other extra-curricular activities than ever before.

More surely demonstrable is the development of the college on the scholastic side. This may be proved by the following list of separations for low scholarship made at the close of the first and second semesters for the last ten years: Class Ist Sem. 2nd Sem. 1924 37 49 1925 32 23 1926 29 20 1927 27 11 1928 25 35 1929 24 6 1930 17 9 1931 12 10 1932 11 7 1933 11 8 Another indication of a similar development is found in a comparison of the present class and last year's class in regard to warnings at the middle of the first semester. This year 73.4 per cent of the entire class at the opening of the Thanksgiving Recess was reported as not having any failure among their courses. Last year, 68.6 per cent of the class was similarly without E's.

It would be easy, as well as useless, to multiply statistics of this sort. They all tend in the same directionnamely, to indicate that the intellectual, as well as the extra-curricular, quality of the student body has greatly improved as the result of the Selective Process.

Acting Dean of Freshmen

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhy and What—the Outing Club

February 1931 By Craig Thorn, Jr. '31 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

February 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPresident Hopkins on Prohibition

February 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1931 By Truman T. Metzel -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

February 1931 By "Hap" Hinman

Charles R. Lingley

-

Books

BooksThe Life of Thomas Brackett Reed

By CHARLES R. LINGLEY -

Article

ArticleSALMON P. CHASE, UNDERGRADUATE AND PEDAGOGUE

October 1919 By Charles R. Lingley -

Books

BooksMemories of Many Men in Many Lands

June, 1923 By CHARLES R. LINGLEY -

Article

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November, 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Books

BooksWILLIAM HOWARD TAFT

January, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleRichardson's New History of the College*

MAY 1932 By Charles R. Lingley

Article

-

Article

ArticlePresident Hopkins Returns to Heavy Schedule

March 1935 -

Article

ArticleLACROSSE

MAY 1973 -

Article

ArticleStudents play design-a-dorm

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 -

Article

ArticlePatience Rewarded

JUNE 1978 By Kenneth Paul '69 -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1925

August, 1925 By Natt W. Emerson '00 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

June 1943 By P. S. M.