WITH SOME OBSERVATIONS ON ATHLETICS IN GENERAL

PRIOR to 1893 Dartmouth had athletics and policies, but the athletics were without organization and the policies were without definition or consistence. Naturally there were episodes and methods to which it is impossible to point with pride; and the statement that in these respects Dartmouth was not unworthy of her competitors is on excuse, but merely a declaration of fact.

The significant events of that date were the inauguration of the Alumni Oval, and the organization of the "Alumni Committee on Athletics," afterwards known as "The Athletic Council." With the movement of the center of sports from the Campus to the Oval came suitable equipment of a permanent nature, and income to relieve the burden of taxation; with the organization of the Council came definite policy and responsibility, the importance of which in giving position and opportunities to Dartmouth teams cannot be over-estimated.

The original constitution of the Athletic Council, drafted by Doctor Cowles and Mr. E. K. Hall, embodied the unwritten methods of procedure so far as they were useful; but this first instrument has been twice worked over with reference to changed conditions and greater efficiency. The present constitution has the approval of the Trustees, of the College, the alumni at their annual meeting, and the undergraduates in mass meeting. Under it the representative governing body consists of three alumni, three members of the faculty, and three undergraduates,—the managers of the three principal teams. At one time the undergraduate representation was increased to five ; but at the request of the alumni the original number was restored, the undergraduates giving their assent.

The College has been very fortunate in the alumni upon the Council, whose interest has been close, active, and elevating; and the student managers have been a capable group, and in general able to take broad and disinterested views.

The Council usually does its business with unanimity. About twice in its history there have been sharp differences between the various elements; but this has been during a period of twelve years, and in that time the Council has been compelled to do many hard tasks, and occasionally to incur the Severe displeasure of the student body. The membership of the managing editor of The Dartmouth was a decided advantage while it lasted, and could have been continued profitably had it not been for the objection to the disturbance of numerical balance. The experience of these years seems to indicate that the undergraduates will meet their duties in a responsible way, and that any division along party lines will be very uncommon.

The first problem of the Council can hardly be dignified by the name of finance ; it was rather the question how to live in a self-respecting way. The earlier times were rich in opportunities for carelessness, irresponsibility, bad judgment, and dishonesty in handling money. Notwithstanding the opportunities, "graft," if it existed, was nearly unknown, but loose methods were prevalent. There was no check on receipts, expenditures were seldom carefully audited, and no great effort was made at the close of each manager's period of service to gather' all the outstanding bills. Resourceless managers met their pressing needs by easily obtained credits, and then through graduation passed into financial oblivion. When the widely scattered accounts were gathered in, the various athletic interests were found to be charged with about $3500—a sum in excess of a year's income during the period when the debts were incurred. Although not legally responsible for these obligations the Council, believing that they were debts of honor for goods that had been delivered to and used by the various organizations representing the College, adopted them and in the course of years paid them all.

These years of debt and frugality were healthy and good. There was an income sufficient for economical support of the various interests, and a small surplus which quickly disappeared to diminish the debt. A few years of modest comfort followed; there was a little savings fund laid by for emergencies, but it was necessary to keep a cautious eye upon the outgoes, And then recently arrived the joyous era in which excellence does not have to wait upon the report of the book-keeper for its accessories.

In 1893-4 our athletic receipts from all sources were $4100; in 1898-9, $5258; and in 1904-5, $20,320.

During these years baseball did not greatly change in either expenses or receipts, though on the whole its net earning power diminished ; track athletics, never more than barely supported by subscription, and without earning power, greatly (and advantageously) increased its expenses. Attendance at the Oval has been gaining in numbers, but the total cash receipts of any game there have never been over $1400. So the increase of income is mainly due to football games away from home.

Each department's accounts are kept separately, and whenever any of them shows a surplus at the end of the season the money goes into a general fund from which it is helpfully distributed by vote of the Council. From this fund come regularly the salary of the Graduate Manager, part of the salary of the Assistant Professor of Hygiene, large sums in support of track athletics, and in improvements upon the Oval, subsidies to the band, to tennis and to hockey, legitimate general expenses, like printing and travelling expenses of the alumni members of the Council. It would be a hard time for Dartmouth Athletics now if any cause, - increase of expenses or falling off of income—should obliterate this rather slight defense against the difficulties of penury.

More opulent institutions have shown how to guard against an unhealthy surplus of the athletic funds, and we are following in our modest way. Coaches cost about $2500 a year; large squads are maintained; a training table is supported; uniforms and appliances are better and more numerous; "teams" mean more men than formerly, and they are transported with vastly greater comfort, and better entertained upon the journey; the various officials are much more free to move, —to conduct difficult negotiations in person instead of by letter, to study the play of opponents, to visit schools for recruits. Some of these uses of money are advisable; others are questionable, either as admissible at all or as to degree and method. Questionable must be distinguished from necessarily bad.

Until recently all money came out of the treasury only upon the order of a member of the Faculty,—the chairman of the Advisory Committee. But more recently disbursements have been upon the order of the Graduate Manager checked only by an audit after the season is over. At a time when the graduate managers— Messrs. French, Hopkins, Witham- shave been worthy of all confidence it may be wise to provide for the uncertain future by requiring the bond which the constitution authorizes, and publication of detailed accounts.

It has been the aim of the .Council from the first to deal with other institutions in a spirit of fairness, courtesy, and business responsibility, and in this pacific endeavor the alumni members and graduate managers have been able to afford us the greatest help. The best evidence that our purpose is recognized is our present freedom from intercollegiate bitterness; there are even those who speak well of us. It was not always thus; it may not have been Dartmouth's fault, but it was certainly her misfortune to feel the cold wind of distrust and suspicion blowing from several quarters at the same time.

The discourtesies, frequently unintentional, of an unpracticed correspondent may not only defeat the purpose of the letter but stir up active hostility. Impulsive editorials in the college press or irresponsible communications to the newspapers easily precipitate a controversy. The abrupt cancelling of long standing engagements, over-reaching, or the suspicion of over-reaching, in accounting for money, and bickering about the make-up of teams produce strained relations. Business dealings between colleges, involving considerable financial interests, are sometimes managed with astonishing childishness, illustrations of which (from other institutions) are reluctantly withheld.

The present peaceful condition of Dartmouth's intercollegiate relations is the result pot of accident, but of much care to avoid misunderstandings, impetuous public utterances, and Unfair or dishonest treatment of obli- gations.

The Council has heartily joined in the plans of the College administration for the better supervision and care of athletic aspirants. All candidates are examined by the Medical Director to ascertain their fitness to enter upon the course of training required of the various teams, and thereafter they are carefully watched by the Physical Director, who has authority to remove them temporarily from practice, or permanently from the squad, if injuries or the condition of their health makes it advisable.

Dartmouth employs professional coaches and trainers, by which is meant teachers who are paid for their services. There does not seem to be any other way to centralize authority, create responsibility, keep the men up to their work, and secure impartial selection of the best men. Personal abuse and lurid language - what the great Daniel Pratt would have appreciated as the "vocabulary-laboratory " —are extrinsic and accidental to the profession of coach or trainer. Knowledge of what he teaches and good judgment in handling men are the essentials, and Dartmouth has been very fortunate of late.

The relative inferiority of the baseball teams to the others is due largely to the lack of a baseball coach who is able to remain with the team through the season. It is hoped to improve this condition before long, although it is difficult to find a man with the qualities desired who is not under engagement as a player as soon as the season opens.

It is a matter of some pride that our recent progress in football has been made under our own system of coaching. And that period during which our teams went out to some contests with the humble ambition to learn what they could from the inevitable defeat is now past. Dartmouth does not expect its teams always to win, but it does expect them to enter all competitions with the belief that no team has any better right to win, and then to play the game honorably and persistently to the end.

On the whole it has not seemed wise to form leagues with other institutions ; this attitude was at first the result of circumstances rather than choice, and if is not necessarily a permanent policy. The history of the various leagues for athletic purposes among the colleges seems to show that while for a time they serve a useful purpose it is one that can generally be as well attained without the league. On the other hand the articles of agreement appear to stimulate suspicion and public bickering, and lead to threats of withdrawal or to sudden and high-handed disruption more or less scandalous or distressing in their public discussion. When eligibility rules are maintained through inquiry and protest by opponents there is constant danger of arousing partisan obstinacy, especially among the mass of undergraduates and alumni who are not immediate parties to the negotiations and who depend upon the swift misinformation of the college community. There is also danger that good athletics will suffer by a tacit understanding that violations of the agreement by one party will be offset by violations on the other side.

The constantly arising questions of what individuals shall play upon a college team are questions to be settled at home, in the honest application of principles that serve their purpose best when openly made known and when fairly in accordance with the conventional standards that experience has made necessary. It is much like personal honor as distinguished from honesty enough to escape the law.

Dartmouth's position is that no opponent (except in the New England Intercollegiate Athletic Association,—better known as the Worcester Meet) has the right to raise any questions concerning the membership of teams, nor does Dartmouth protest opposing players. Such an attitude places the obligation where it belongs - at home, and requires that those who pronounce upon eligibility should do so actively, and to the best of their ability.

Investigation and information are confessedly difficult and often insufficient in such matters. The Council does not require any individual statement from athletes as a whole—the so-called '' ironclad"—as there is good reason to believe from others' experience that such statements are not trustworthy; nor does the Council act as a detective bureau to ascertain the exact doings of every athlete during his past life or his last vacation. It would be impossible, and degrading if possible. It asks those in immediate charge of teams to put no men upon them who would bring discredit upon the college, and to refer doubtful cases to the Council; and it investigates all cases brought to its notice, either through the press, or common knowledge, or volunteered information. The man himself is asked to tell his story, and his word is accepted unless either in. his own story or in other sources of information there is evidence that he is not telling the truth.

Of course a liar may remain in good and regular standing, but this is only a temporary misfortune; the responsibility remains on him, the lie will be exposed before long if he is .valuable enough to notice, and will follow him long enough to make, him a useful warning. No other method seems possible in dealing with young men who must be assumed to be honorable and truthful, and no other method is so effective in the long run. The weak point of this or any system is in the cases that do not come to notice, where no cause for investigation arises. This however is paralleled in the execution of the law anywhere. The results are good but not perfect.

The following are Dartmouth's rules of eligibility, and obviously they cover ground upon which there is much difference of opinion :

*XII. Any student of good and regular standing in the College shall be eligible to participate in intercollegiate athletics, with the following exceptions:

a. No student shall take part in intercollegiate contests for more than four years.

b. No student who has ever competed in any intercollegiate contest while a member of any other college or university shall be eligible until he has been in attendance at Dartmouth as a registered student for two full consecutive semesters.

c. No student taking a post graduate course or member of any graduate school, nor any member of the medical school, shall be eligible, provided that this rule shall not apply to Seniors of Dartmouth College taking courses in the Medical School, the Thayer School, or the Tuck School.

d. No student who is induced to enter or to remain in college for the purpose of participating in athletics by the payment of any part of his expenses by any one whomsoever, shall be eligible.

e. No student shall be eligible who shall receive, in order to enable him to take part in, or for participation in any form of athletics, any pecuniary return or emolument, with the single exception that he may receive from his college organization or from any amateur organization of which he is at the time a member, an amount by which the expenses incurred by him in representing such organization in athletic contests exceed his ordinary expenses.

f. No student who has played on any semi-professional nine, or any socalled Summer'baseball team, shall be eligible until he has received special permission from the Athletic Council.

g. No student shall be eligible who when called upon to do so fails to establish his amateur standing to the reasonable satisfaction of the Council.

The object of eligibility rules is to prevent abuses, and any code is arbitrary in its nature. The rules cited are, with minor modifications, those existing in all institutions of athletic repute, together with a section debarring graduate and professional students, which is not yet of general adoption.

Section a encourages college students to go into some other business in life, after playing four years upon college teams. The four years need not be consecutive nor at one institution. It only occasionally affects our teams by debarring some valuable athlete who requires, or takes, more than four years for the Bachelor's degree. Under it, however, in other institutions, a student may play four years in a professional school, and in some cases, by absurd definition of "intercollegiate" contests and by the nice criticism of academic equivalents which eliminate certain years, he may make a fresh start in an adopted institution.

The object of section b is to avoid the hasty transit of fine athletes from one institution to another,—a movement which is always open to,the suspicion of motives not wholly based on superior educational advantages. This rule, it will be seen, does not require the year of waiting from students who have never taken part in intercollegiate contests in the institutions from which they come.

Upon the provisions of section *c a constant difference of opinion is to be recognized and respected. Dartmouth adopted this rule under stress of weather, but has retained it in calmer times, and to some it is a source of great pride that the admirable teams lately representing her have been a compact body of her own undergraduates in full standing for a degree and maintaining themselves under a rather severe rule of the faculty which requires their standing in all their studies to be ascertained every two weeks and men below in two studies to be taken .from the squad. It is a view that has some reason on its side that graduates of other colleges should not represent an adopted alma mater in competitive sports, that students in professional schools owe their time to their profession, and that it is not practicable to distinguish between genuineness and pretense in professional study until at least the football season is over. If one is willing to think reasonably of this question let him inquire how much legitimate benefit to our teams would come from the abrogation of section c; and if he thinks that some advantage would accrue from the eligibility of students in the Medical School, in the Thayer School, in the Tuck School, and in the other graduate courses of the College, it may be asked whether at a time when sixty to one hundred undergraduates are willing to appear daily on the field through the season and when the strength of the teams lies not in accessions from without but in training from within, it is not a wiser policy to use the willing undergraduate material rather than to keep the coveted positions for belated stars.

There are some who believe that the period of scouring the country for burly toughs, and loosely attaching themx to schools of Blacksmithing or Brickmaking, is about over in the less reputable institutions, and that even those who mean to be fair in the application of their rules will cease to use the graduates of other colleges who are matriculated in their professional schools.

In sections d, e, f, and g is incorporated the usual amateur code with a little more than the usual freedom of interpretation. The past is not absolutely unforgivable; it is not likely that a student here would be debarred because he had played marbles for keeps, or helped in the gymnasium of his preparatory school. It is not assumed that all summer ball is bad, on the contrary some is believed to be thoroughly wholesome; but in those cases in which appearances are unsatisfactory the student is expected to come forward and explain.

Section d renders illegal a practice thoroughly corrupt and corrupting,—the purchase or subsidizing of athletes. It is the more corrupting because so many fairy tales are floating about each year. It is, known at all the colleges except the one most concerned, for just what price the wonderful Mr. Punter chose one college instead of the six others that he was surely going to enter, and from the preparatory schools, if the bribery does not begin soon enough, young Massey and the redoubtable Wayte write and inquire, "What are you going to do for me"? It is certainly believed among the preparatory schools that a college course of financial comfort awaits the star athlete, and it is known among the colleges that other institutions are buying the men that would otherwise come to them, and even tampering with those who are already on the ground.

The truth about these matters is not ascertainable, least of all by anyone who would object. It is to the interest of the negotiable athlete who has not made his market to invent tales of the valuable offers he has under consideration in the hope of eliciting one genuine tender; and it is to the interest of the athlete who is receiving his consideration to keep quiet and let others do the talking. Enthusiastic undergraduates make wild statements concerning their power to influence the scholarship funds of their college, and influential alumni offer to write to the President. But the entrance requirements and the scholarship funds are administered with a sad lack of consideration for the athlete. In fact he quickly falls under someone's suspicious eye. If he is needy he has the same chance with any other needy student ; if his scholarship is good enough he will be admitted on the same basis as any other.

It is reasonable to believe that seventy-five per cent of the tales of athletic salaries (as they are told of other institutions) are false, and the remainder are only partly true. It is true that some alumnus, or group of alumni, or wealthy student does occasionally determine the selection of a college by notable athletes through the promise of pecuniary aid. Sometimes they pay and sometimes they do not. Such money is, not very abundant one would think, and any knowledge of the transaction comes to light only by accidental disclosures made long after the time for remedy is past.

There are some opportunities of employment under student control, as at eating clubs, reserved for the athlete ; but the most dangerous use of the athletic funds in this respect is in the so-called "training-table." Here a group of athletes supposedly paying the price of their board previous to the organization of the table, receive food of extravagant cost and in some cases manage to evade payment altogether. The two chief advantages of the training table are that it keeps the men. together tinder the trainer's eye, and that it furnishes sufficient nutritious food to men who might have to economize too closely.

The principle laid down in sections e and g is the occasion not only of some evasion and deceit but also of some difference of opinion upon its advisability. If all the faculty and all the alumni of the colleges were agreed upon the amateur standard there would be much less difficulty in maintaining it. The question at present is full of difficult discriminations.

An amateur contends for the zest and the love of the sport, and a professional for some gain or emolument. The difference is in spirit, and is therefore very poorly defined by rules. A man whose spirit and purpose are wholly professional may by some evasion make himself appear to be by definition an amateur, and another whose whole interest lies on the side of good sport may by some ignorance or carelessness place himself outside the technical line of amateur definition.

Moreover there does not seem to be any moral issue involved in the bare question of amateur and professional athletics. A very honorable man may make his living by baseball, and a wholly unscrupulous one may preserve his athletic virtue long enough to finish four years of rowdy play upon his college team. The moral question comes along quickly enough in the chicanery, subterfuges, and out and out lying by which players who have gone over to the money-earning class seek to retain a place among amateurs.

The general question is one of convention and expediency, and persons who might agree in the field of morals differ widely here. Possibly the exclusion of professional athletes from college sports is least satisfactory to those who have not considered the matter from all points of view, and to those who lose by the exclusion. Even long experience, opportunity to test the difficulties of athletic administration at all points, to note the trend of the times and to hear forcible expression from those who differ do not bring solution of all the difficulties of the problem.

The great practical reason why every college expecting athletic honors must maintain the amateur standard is because it is the generally accepted standard, and never more than at present. The sporting editors, the pungently critical reformers, the fabricators of all-America teams were never more keen in their scrutiny. Those in charge of athletics in the more prominent institutions are in frequent receipt of inquiries concerning suspected men, and the criticisms of a successful team do not err on the side of leniency. The individual players are far more careful than formerly to show a clean record, and the general college sensitiveness, though not all it might be, is increasingly helpful. No college can openly depart from the accepted standard without being branded as an athletic Philistine; victories are discounted as being "of another class," and defeats, which are fully as frequent under a loose as under a strict standard, are matter for ridicule without and recrimination within. Even if the colleges agreed among themselves to be less exacting in the make-up of their teams,—and such was the tacit understanding a few years ago - there is outside of the undergraduate world an army of lovers of good sport who draw the line with great care. One college could not long defy this public opinion; all the colleges cannot at present be drawn into an agreement for the open door, and if they could their graduates would find themselves on the outside of amateur athletics.

It seems needless to say that if a college undertakes to maintain the amateur standard at all, its only course is to maintain it honestly, without favor, to the best ability of those in charge. The greatest difficulty now lies in the fact that those who decide are not in the way always of knowing the facts, and may be deceived. But these difficulties are growing less for the reasons already given ; someone will find out the facts and disclose them, to the discredit of the individual, the team on which he plays, and the college.

Three points are urged by those who are not responsible for the practical working of athletic affairs and by some of those who are :

(1) The standard should be academic, and any college student should be free to take part in the games of his college, provided only his scholarship is satisfactory to the faculty.

(2) The poor boy ought to be allowed the opportunity to help himself in any way that he can.

(3) The amateur rule is the occasion of so much lying and trickery that it ought to be abandoned in the interest of good morals.

Doubtless there will continue to be difference of opinion on these points. But to me it seems as if the simple academic standard was unworkable. It looks like a return to the rottenest period of college athletics. It puts the college man in a distinct class of sportsmen; it allows him to hang around the college and play upon the teams as long as he can find an academic reason ; it enables him to migrate from college to college according to the inducements, and become immediately available for athletics ; it permits a salary from the athletic funds or from private subscription; it admits the toughest class of professional sports to the college games during the period that they can keep their heads above the conditions; it brings a strain and pressure on the individual instructors which some of them are unable to bear ; it opens the way to absurd and invidious definitions of academic equivalents ; and in the case of matriculates of professional schools it would often happen that the academic standard would be applied only after the purpose for which they entered the school had been subserved.

It might be answered that at all these points there would of course be restrictions. But if that is so, it certainly would not be the simple academic standard so often urged ; and moreover all the difficulties of administration would appear at another place.

The second point would have more weight if it did not raise a false issue. Every one has sympathy for the poor boy who is trying to help himself along. It is not discreditable to him to hire out to play baseball all summer, if that is his best chance; the discredit comes when he tries to impose himself upon the college arena as the amateur which he has ceased to be. He might pass at home, but outside his own college he is like a debased coin in a foreign land.

The third point,—the removal of restrictions to avoid the bad morals of their evasion, certainly affords food for thought ; it can have no adequate disussion here. It seems like taking down the fortifications because they are likely to be attacked, and involves a discussion of the purpose and usefulness of the fortifications. Examinations are the occasion of bad morals, but we go on in constant and successful struggle. That is, dealing with material which is constantly moving up from below, - from the crude to the refined - we are never free from bad morals ; but following any given set of men through their educational course we observe a great gain in selfrespect and the sense of honor. It is not so bad a plan to " hold the fort" for a time and expect improvement of the bad morals.

The practical reason given - that our amateur standard is in conformity with the existing code—is of course a temporary reason. If the standard is wrong a steady fight against it by those who have at heart the best interests of school and college athleticswould sooner or later prevail. But is the line between amateur and professional undesirable in school and college sport ? Are we prepared to say " There is no occasion for all this stir about amateurism ; take what you can get for your services, it differs from no other well-earned money?"

In theory at least, our school and college games are the culmination of periods of training in which many take part, and the interest and excitement centering in. the culmination is the power that makes the more useful part - the daily training, goon. We accept some conditions of a less desirable nature for the sake of the more desirable ones. In the professional field the sole purpose is a competition, spectacular and successful. No professional athlete can continue to please his constituency who is not successful, or who does not contribute his full share to success. It is not a question of so much work for so much pay. The people call for winners. Hence there develop the ethics of the would-be-winner. A would-be-winner may rely solely on the cultivation of his skill; but he competes and associates with many who take advantage if they can; his livelihood is at stake and his place in the popular favor, So the suggestion comes with force to load the dice if he can, "to make things come his way." With the spirit and wish for the unfair advantage comes also the wish for the quick and crooked dollar. Of course the professional athlete may withstand these and other temptations, but they are in the air he breathes. Now the youth who is exposed to these conditions in even a slight degree brings into the school and college world notions that do not belong to generous and high-minded youth. "Kick whenever you think it will do any good," "Rattle their pitcher," "Lay out their best back," " Cut second base if the umpire isn't looking," " Pocket the favorite runner," " Steal the ball if you can," " Get even with him in the next scrimmage," are unlovely principles, and it is painful to see our choicest young men - those who are being trained for service to the world and for leadership—imbued with the win at any cost spirit, which if it does not wholly come from the professional world finds its greatest encouragement there.

The very heart and life of sport, however, is friendly rivalry. It is a relaxation, a diversion, a relief from cares, bitterness and hostility. Its essence is in good fellowship. Its foundation is in friendliness. Herein lies the simple test, and we are in constant-danger of losing the spirit of generous and friendly competition in the intense and highly organized athletics of today. If one should allow his mind to dwell upon the worst phases of college athletics it might seem as if we were losing ground. The scrupulous personal honor, the manly frankness, the high-minded and generous spirit that takes no advantage, that refuses to brawl for small rights, and that might give such noble promise of good citizenship in the larger affairs is sometimes crowded into a corner where it dares not show its colors, by noisy self-seeking, petty cunning, greedy over-reaching,and athletics-forwhat-there-is-in-them. The majority with honest impulses and gentlemanly instincts too often join in the hasty applause of some shameful practice of which nothing defensive could be said except that it helps to win, or that others do it.

The worst phases are not the chief phases, however. With the worship of the athletic hero there is some appreciation of the excellent qualities and long endurance that go to his making; with the noisy triumph comes also the power to stand by a losing champion ; the catabolic genius finds now a better outlet for his energies than putting cows in recitation rooms, or, we trust, painting statues red ; the whole inner college life is sounder, more free from debauchery, violence and malice, even if less scholastic, than formerly.

And as one observes, looking over many years, how much athletics have done to uproot and destroy some of the college vices, it is possible to anticipate still more and to hope that from the great opportunities, open discussion, and clear knowledge of the college man will develop a variety of athlete—type of the good citizen—who will cut loose from the low ethics of those who have never been taught any better, or of those who must " deliver the goods" by fair means or foul, and from the notion that wrong is righted by -more wrong, and from that other notion, as false in sports as it is in business, that honesty cannot win, and will stand openly for perfect sportsmanlike fairness, will tolerate no tricky players, corrupt or incapable umpires, or mercenaries masquerading as amateurs. The colleges could thus infinitely benefit the whole range of lower schools and the world of honest sport. The average is made up of the high and the low, and if the college standards are not high how can the average be raised?

*From the By-laws of The Athletic Council, Edition of 1904.

Edwin J. Bartlett '72, Chairman of the Faculty Committee on Athletics, and Secretary of the Athletic Council

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT ROOSEVELT'S RAILROAD POLICY

December 1905 By Frank Haigh Dixon -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1905 -

Article

ArticleTHE new catalogue, for 1905-1906,

December 1905 -

Article

ArticleTHE KOSCHWITZ LIBRARY

December 1905 By P.O. Skinner -

Article

ArticleTHE FOOTBALL RULES

December 1905 By F.G. Folsom '95 -

Class Notes

Class NotesANNUAL DINNER OF NEW YORK ALUMNI ASSOCIATION

December 1905 By Lucius E. Varney

Edwin J. Bartlett '72

-

Article

ArticleUNDERGRADUATE AFFAIRS

January 1915 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

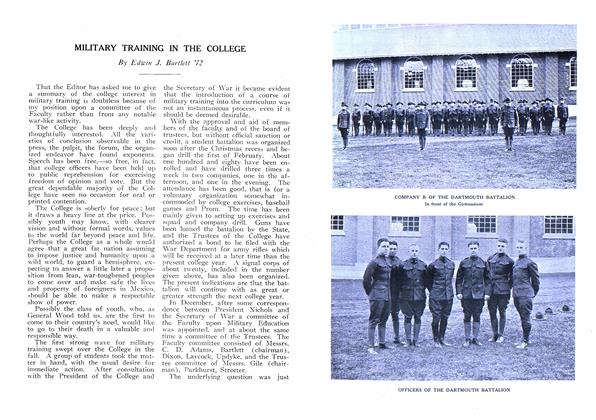

ArticleMILITARY TRAINING IN THE COLLEGE

June 1916 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

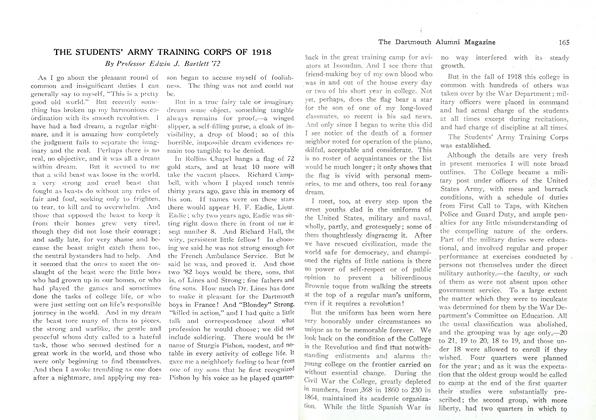

ArticleTHE STUDENTS' ARMY TRAINING CORPS OF 1918

February 1919 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE REJOINDER OF JOAN

August, 1923 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleMATERIES MEDICI

June 1924 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72