IT had taken a week to get my nerve up. But there I was in Coach Crouthamel's office three Augusts ago, trying to tell him why I wasn't going to make double sessions that fall. I had decided to take a year off from school, and quitting football was the most upsetting detail to take care of before leaving Hanover. I had worked that summer as a waiter at the DOC House and had seen Jake often - sometimes in his office in Davis Varsity House when I was picking up installments of my playbook, sometimes in the weight room of Alumni Gymnasium, one time even at a local merchant's Fourth of July celebration. We had never talked at length about anything except football, but now I was almost in tears trying to tell him about my frustration - needing to break the compulsive pattern of playing football and neglectipg my studies every fall - and my confusion - trying to make a decision about continuing my premedical studies. He listened closely, smoked several cigarettes, looked in my eyes. I finished talking. He put out his cigarette. He didn't say anything for a while.

He began slowly, telling me I would be missed on the playing field that fall, saying he was sorry that I would miss sharing the fun - the practices, the road trips, the games. Had he stopped there, I would have always thought that he had told me the same things he told everyone who quit the team. But after pausing, he continued. He spoke movingly about confusion and frustration and not knowing what to do in life. He suggested that maybe the people who were comfortable not knowing exactly what they wanted to do were deserving of the most respect. He finished by asking if he could do anything for me, encouraging me to keep in touch, shaking my hand. I left his office feeling relieved, feeling confident for the first time that taking time off from school was a good thing to do. When I heard later in the fall that Jake had resigned as coach, I knew why on one August afternoon he had shown such understanding to a scared young man trying to change his life. So I left Dartmouth, found work in the operating room of a large hospital very near New York City, and began gathering impressions.

Bullets - "Joe," I say, "can you hear me, Joe?" His eyes are closed. "We're going to the operating room, Joe. You'll be asleep soon." He raises a few fingers. "Good, Joe. First I'm gonna shave your head though, okay?" No response.

The bullet hole - small, clean, circular, speckled with burn marks.

Joe probably doesn't remember hearing the shots fired from a car that drove past the streetside windows of the bar. The .38 caliber bullets crashed through the windows. One caught Joe in the head. "... a little while longer, Joe. Just hang in there."

The surgeon works quickly, checking xrays, probing spots of burned tissue in the young man's brain. "Could you adjust the light? That's it. You say he's an engineer, eh." He seals a bleeding capillary with the cautery - the smell of burning flesh. "It's good that he's not an artist or a surgeon he'll have a little paralysis on his left side." A sudden drop in blood pressure. "Could you get another unit of blood?"

Courage - Late afternoon, only one more operation on the schedule, everyone anticipating regular dinner breaks tonight. A nurse hangs up the phone: "Doctor Madryos, the operating room just called again. They want him sent up right away. They say that they'll take responsibility for his physical." Dr. Madryos - a man in his late sixties, a dark suit - standing at the nurses' station, wondering why the resident neglected to do the required preoperative physical, deciding to do it himself, thinking that they never do a thorough physical in the OR. Mumbling audibly about the delay, the nurse follows Madryos to the patient's room. Madryos ignores her comments.

Madryos enters the room. The old man smiles. Madryos listens carefully to heart and lungs. The nurse slowly burning in the corner. Madryos checks blood pressure, pulse rate, respirations. Listens again. Reassuring, talking with his hands - kneading the old man's shoulders, holding his hand. Signals the nurse to leave the room with him. The surgeon in scrub-garb has come down from the operating room and storms down the hall towards Madryos: "What the hell is going on down here, doctor, I want to get out of here before midnight tonight." Madryos ignores him for the moment. He says something to the nurse. She dashes to the medication room. He follows to help her, pausing long enough to tell the surgeon that the old man is in congestive heart failure. Madryos returns to the room, administers the drugs. The old man rests. Had the operation not been stopped, the anesthesia would have killed him.

Afterwards, Madryos answered my questions about courage, responsibility, not taking the easy way out. He talked about swearing an oath to protect, preserve, and defend life, about his responsibility to a frightened old man unable to speak for himself. My questions interested him. His idealism amazed me, but he left me with a warning: "So you're pursuing a career in medicine. I wish you luck, but you'll be disappointed." .

Last Words - "Hi, Mr. Crooker," I said, "How do you feel tonight?" "Do you really want to know?" His reply carried an ominous rasp with it. I answered, "Yes." He smiled, gave me a card printed in fine letters by hand - "Back hurts, throat hurts, legs sore . . . body aches, but thanks for caring enough to ask."

The cancer had ravaged his throat. Next morning, the surgeons would perform a laryngectomy. With his larynx removed, this 72-year-old man might never speak again. I had noticed that he had tacked an order onto his operative permit saying that he forbid the use of any extraordinary means to keep him alive. He shared his last spoken words with me, words about cancer, about living - "Do what you want to do, it's the only thing you'll do well," about dying - "I'm not afraid of dying, only of living too long." We shook hands and said goodbye.

And so my year away ended. I had left Hanover seeking answers to.my questions. I returned to Dartmouth last fall with many new questions and very few answers. Former Dean of the Faculty Arthur Jensen said last spring, "You come here for four years and you get so you can ask the right questions, and then you find that nobody - but nobody - knows the answers." For some of us, it has taken five years instead of four, but maybe that's the price of learning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

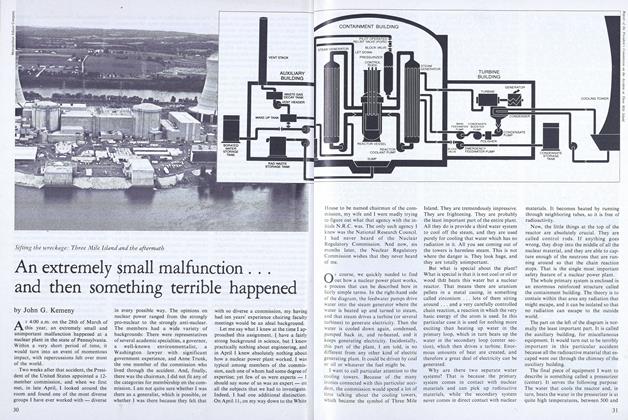

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

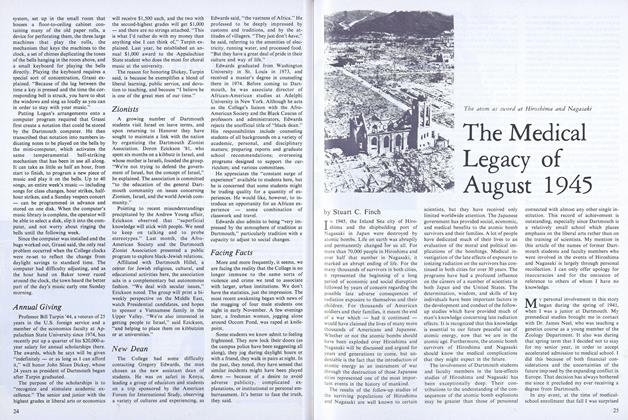

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

December 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE

MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80

-

Article

ArticleThe Bard's American Friend

September 1979 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleZombie of the 1902 Room

October 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Great Society

April 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Books

BooksExperiential Education

OCTOBER 1981 By Michael Colacchio '80