Writing upon college discipline by one who knows is doubtless an indiscretion. I have often longed to be indiscreet, but now that the opportunity is present I am like the comic man who did not dare to be as funny as he could. Two fruitful topics are barred anyway,—matters which in the long stretch of years I have forgotten, intentionally or otherwise, and matters which would uncomfortably indentify active participants. Generalities are far less piquant than concrete stories of the misdeeds of John Doe and the rest. But John who cribbed in examination is. now an honored and honorable member of society, and Richard Roe, his partner, who screwed up the door of the recitation room with the professor inside, has modified his idea of a joke and is now a joy to all who know him, while James Hoe, who really disgraced himself and was allowed softly and silently to vanish away, is a deacon in the church and a large contributor to the Alumni Fund. No, it would not do.

The stories of turbulence, insubordination, and personal annoyance by students in the first half of the 19th century seem incredible to the college officer of today. (And the same may be said of some of the regulations of the Trustees and Faculty.) But one may read of them in Professor Lord's citations from the college records and other sources. And these citations are matched from the experience of other institutions during the same and even a later period. Strachey, writing of Eton at the time when Arnold became Head Master of Rugby, 1828, says its government was a "system of anarchy tempered by despotism;" "But there were times when even that indomitable will (Keate's) was overwhelmed by the flood of lawlessness. Every Sunday afternoon he attempted to read sermons to the whole school assembled;. and every Sunday afternoon the whole school assembled shouted him down."

Whatever the customs elsewhere, here, removing an offending stove from a recitation room and throwing it into the river; firing a gun so heavily loaded as to break 320 panes of glass, in front of the buildings, in retaliation for offensive discipline; turning the occupants out of a dilapidated building and razing it to the ground: tarring and feathering a bad man; blowing a horn in recitation; wrecking a bookstore; go beyond the commonplace in college pranks, especially when superposed upon all the familiar disorders.

Some of this was matched by gumshoe detective expeditions of the faculty even in disguise, and by police methods doubtless as vexatious to the professors as provocative to the students.

From 1868 (when I first had personal knowledge) there was a diminuendo in all these practices, not without occasional crescendo bursts. And the diminuendo has continued.

If you ask me why the change, I reply at once, "Because students of the present time do not care to bother with these forms of entertainment." No amount of policing could hold 2000 students in check during all the hours of the twenty-four. The searcher for ultimate truth returns with another "Why". "Why do they not care" ? Here various philosophers will differ. My own answer is that the greatest factor in bringing about this most welcome change in college manners is the development of athletic sports within and without the walls. It has been a steady influence for self-government upon the students, and an influence upon the faculty for sympathy with the students' interests outside of the curriculum. And these influences have reacted upon both groups. No student can horn or otherwise abuse a professor after finding him to be a good sport in a hard-fought game of tennis, or a good cook in one of the cabins of the Outing Club. No instructor after acting as referee in field sports, or after talking over affairs of college interest with a group of undergraduates on the way home from a football game can pussy-foot around to see whether his agreeable young acquaintances are playing cards when they ought to be studying.

There are, of course, other causes contributing to these more tranquil days and nights, to be emphasized according to the personal equation of the emphasizer. Such are, the trend of the times and public opinion, more refined surroundings, the critical attention of the newspapers, a feeling of nearness and neighborliness instead of isolation, a wider area of patronage introducing diverse habits of thought, the complex organization of the modern college, the elective system, and the belief that the teacher really has something to give. Upon these as a basis floats, as it were, the beautiful flower of self-government. The election of studies has brought relief to many a teacher compelled to carry along men who had no taste for his work, but who really were interested in something else which they were unable to take. More frequently than is generally known some Ph.D. freshly decorated from the graduate school, with vast learning, and with vast contempt for the teachers who have not had his advantages and for the "boneheads" to whom he has to devote his time, or some professor called from another institution, with individuality and superficial mannerisms, will arouse the hostility of the quickly and crudely judging undergraduate as suddenly as one dog hates a stranger dog upon the street. Electives save him from serious trouble until his good qualities develop or become known. No longer can the hostility of a whole class swell around an instructor till it bursts into storm. The courses are elective, and the humorous undergraduate who did not take the odious course remarks to his grumbling chum who did, "Well, it serves you right for electing him when you could have taken Tommy." (Tommy being the "most popular" professor of the year).

Horning, an unpleasant custom seldom warranted by even the crudest justice, was deliberately and definitely abandoned by the undergraduate body about twenty-five years ago, and the faith has been kept ever since.

I was mediaeval enough in college life and instruction to behold and even to share in some of the obsolete methods of forcing good order. I have seen with pain a president of the college work his way to the center of a rush and emerge therefrom with the massive club of contention called a cane, while members of the faculty hovered on the edges of the disturbance ordering men by name to desist. I have seen another president intercept a cane and its escort of mighty men, and by force (constructively) take possession of the stick and foil the stalwart combat troops. I have seen a president repeatedly enter the Green to shoo away students who were passing ball or playing tennis during study hours,—a painful duty which no one else seemed disposed to undertake. And—worse luck—l have been repeatedly summoned on the possecomitatus, "to assist the President in the Education and Government of the Students", to maintain order, and especially to interrupt some merry and porous group engaged in absorbing the product of Bellows Falls from a barrel, in Bedbug Alley or back of Culver. It was all wrong; but these presidents lacked moral courage to upset the precedents handed down from earlier times, though no one could charge them with lack of any other kind of courage.

Doubtless there are occasions in the history of every college when the highest authority must intervene for good order. The occasion comes when, by reason of some special excitement or provocation, the students, for whom the college is to some extent responsible, threaten the peace and order of the community. Then, if the dean is too light a weight for the emergency, the duty, may fall upon some highly respected member of the faculty or even upon the president, There are modern instances. But these are not occasions for the use or show of physical force by college officers.

The time has gone by let us hope, and in hoping touch wood to confound the ginx, when college faculties find it necessary to execute severe justice by the wholesale, upon ten, twenty, half a hundred at a time. I have known it done. I have been one of a tribunal without a dissenting vote. But with what is known as afterwisdom I feel that there was something wrong about it. Can it be that in such discipline there was a prompting of human irritation? Was there a feeling that the law must be maintained even if it broke some one's suspenders? I know there was the mortmain of precedent. For instance, "It has always been our custom to separate from college any young man detected under the influence of intoxicating drink." I may have assented to that notion once; I do not now. And let no one jump to the conclusion that I favor or condone inebriation. But youth is a time of experiment, and if an adolescent experiments once with a dangerous drug to his physical and mental detriment the lesson may be very valuable. At any rate he is not a danger to society until he repeats, thus substituting illustration for experiment.

But granting that in these cases of multiple execution there was no avoids ance of the next step when the crisis arrived, I firmly believe that in nearly all such college convulsions the wrong chemicals had been mixed, or the right chemicals had been left unmixed, by earlier carelessness or clumsiness. College lads are like lambs or like hornets according to the way you take them, and their ideas of what is fair and just are often surprising to their elders. Once a learned and amiable member of the faculty—not the one you think I mean—and his classes were furnishing the college an illustration of mutual incompatibility, and I was one of a faculty committee to meet representatives of the most riotous class in an effort to save the situation. But their hearts were hard to our statements: "He doesn't even keep order in his classes", they said.

In dealing with them it should be remembered or known that when they are calm they are reasonable, therefore reason like a vaccine should get in its work before the contagion of excitement. When responsibility is placed upon them they take it as a sign that they have put on the toga of manhood, hence an advantage of responsible student councils. Marvelous rumors, fairy tales or garbled verities, float about the college, potent for antagonisms, hence the wisdom of actively spreading the truth abroad. There are a few, and only a few, affairs in college management which it is best to hold in secret.

The attitude of the public towards the collegian is usually manifested by ferocious growling until it comes to a showdown, when a sudden gentleness develops. "We mustn't be too hard on the boys; we were boys ourselves once", is the idea. If more of the public could see them in their normal haunts, where the mass are quiet, orderly and busy, their judgment would be better. The student's offenses against the public are noise, often out of place but not really criminal, and sins against property,—damage, destruction, appropriation, failure to meet obligation. From the resulting predicaments he usually escapes on his own terms,—settling the bill. Less childish offenses are often condoned. Once upon a time the lone policeman of Hanover, in the discharge of his duty, undertook the arrest of an erring citizen. The plaints of the malefactor came to the ears of a group of playful students who made game of the officer of the law by roping and otherwise impeding him with some roughness. The constable, who was plucky and efficient but not sympathetic, landed his quarry and then lodged information higher up against his persecutors: It was necessary to sustain the' officer, and the case went to the grand jury before the session of the county court. The grand jury dismissed it on the ground that it was only a college boys' prank. It was a lamentable failure of justice towards one of the most unforgivable of minor offenses, and yet there were law-abiding citizens even upon the faculty who were glad the case went no farther. We have known, have we not, of instructions issued to the police in a large city to be very careful of the college crowds publishing joy or drowning sorrow after a big football game? The law, the police regulations, cannot reach with any evenness, the college student in minor misconduct. Public opinion will not permit it. lam sure that the same could be said of public opinion and college discipline, if the public had an impulsive vote with the half-knowledge which reaches it.

Itemized, the details which may call for censure or excision are not numerous.

First of all is the ordeal of scholarly sufficiency. There is objection to this test, but I do not think the objection is reasonable. Whenever Hercules or Samson is ejected some one gets harsh expostulations. The parents of "Junior" may find excellent reasons why the dear boy failed. But after all it is not difficult to meet requirements which consist so largely in being and doing what all, if they choose, may be and do. If Samson and Hercules arid Junior will not, or in rare cases cannot, cheer the instructor by their presence, get in the theme, the report, or the experiment on time, focus attention upon the business of a short hour, and study just a little now and then they may properly cede their places to those who will perform aright. They are entitled to fair treatment, and they get even more. Since they are perhaps inexperienced in punctiliousness, poorly trained at home, and unimpressed by information that year after year the College is compelled to go on without certain egocentric persons who will not do their studies, they need and get most competent supervision and warning before the final disaster. They depart upon the record of that which they have left undone, but always with opportunity for appeal and a hearing.

Extremely different is the case of Bill Sikes who offends against the criminal code. He may gamble, steal, do acts of violence, or become the cause of public scandal. He is very uncommon; but when one considers the thousands who pass through any large college, it is not strange that in certain circles his memory is fresh though not fragrant. Some say -that the law ought to get him, and occasionally it does, but I do not think the college ever turns him over to the law. It even postpones action that might be prejudicial, if legal processes are in operation. He cannot stay in college to be a center of vice or crime, and yet his case is now understood to be difficult and delicate. He may need proper food, or the care of a wise physician. To make public his disgrace might ruin him for life; so where the matter is not already notorious Bill's misdeeds are not published abroad, and he is given the chance, in absence, which may, and often does, restore him to sound manhood.

From the pranks of a crowd of students released from routine duty the beholder might suspect a good deal of tomfoolery in the recitations and lectures. But this would be a mistake. It is not considered good sport. The individual who tries it on makes himself disliked all around. Combinations against scholarly sobriety have been known, and that professor or young instructor who has allowed his class room to become by precedent or tradition the home of horseplay or comedy has small chance of recovery. It may be funny to have a whole class rise as one man, take off their coats and hang them over the seat, and a little later rise again and resume them, all with perfect gravity and without visible signal, but it is not intellectually stimulating.

"Cutting" in a body is obsolete as a game, because with the liberal allowance of cuts and the definition of their use there is no great fun in lawfully using up a cut which may be much more valuable at another time.

Leaving out of consideration, then, delinquents in scholarship, who are attended to in a well-defined and "impartial manner, college discipline of the present time applies to the rather rare cases called criminal, but requiring most careful treatment, and minor eruptions of lawlessness and disorder upon which the public looks with great leniency, and which the sinner gleefully recalls in the hearing of his sons in later years. It would be difficult to draw a sharp line between the malum prohibitum and the malum per se upon which President Smith used to discourse. A malum perse is naturally a. malum prohibitum; and a malum prohibitum (of which the fewer the better) easily becomes a malum perse because it is prohibitum. The simplest mind can discern the difference between throwing snow-balls in the college yard and cheating in examination, or howling at the moving pictures and burglary, but there might be argument about the immorality of baiting a policeman, obtaining apples directly from the orchard, or breaking the speed.laws.

And where, by the way, is the man Bible" which, with its prohibition of cards, and of musical instruments during study hours, and of disrespect to college officers, pointed out to us the straight and narrow way ? Gone, mute as the harp that once through Tara's halls.

And that list of nicely graduated penalties is probably now on a high shelf in the safe that keeps the records. "Reprimanded by the President"? It isn't done. The youth who needs it will hear plain language in an official voice, but not because he has been voted a reprimand. When you consider, it is a difficult task to administer a well-constructed and powerful reprimand to a polite young man with shining hair who trustfully responds to your invitation to a dual meet, without so softening it with the milk of human kindness as to take out its sting and its official tone. But humble "probation" has grown to be the mightiest word in the disciplinary armament. Probation is nothing; but someway entangled in the word is complete abstention from all those interests which make it worth while to go to college,—football, dramatics and the rest. The punishment fits the crime. "Rustication", mollified as it was by the kindly clergyman and the village belles, is no more. And there is good old irrational "suspension", gone. Not that it could not be, but it is not. It put the sufferer and his instructors at a disadvantage for the remainder of his college course. When he must go he is "separated from college", the dreadful uttermost penalty of "expulsion" being so rare as to be almost unknown to me. But in some peculiar cases, such, for instance, as seem to arise from physical rather than moral pathology, father is given "leave to withdraw."

Although I have heard the mode of procedure in the case of college misdemeanors questioned and even criticised, I have never heard it defined. I doubt if it has definition in terms; but all methods of judicial action are of interest, and this is a development away from execrable methods of dealing with the young. In theory, it is the action of a body whose prejudgment is favorable rather than adverse or neutral to the respondent. Punishment of the culprit is not so much the aim as protection of the rest. The lasting and often unjust effects of publicity are avoided. The compulsions of criminal courts are absent. Special weight is granted to the statements of the individual under examination. And the process is between man and man without professional representatives.

The time was (within my memory) when the whole faculty were judge, jury and executioner, often to the disadvantage of the respondent, and with occassional burlesque embellishments. A selected group administer justice now, with reference, occasionally, of peculiar cases to the president or dean. No student is condemned without opportunity for a hearing, but as there is no authority for bringing his body before the tribunal he may not escape judgment by refusing to appear. He may be confronted by accusers; usually he is not, as accusers of students are very reluctant to appear. He is expected to answer truthfully for himself, but is not asked or encouraged to give information concerning other students. Unless there is good evidence that he is lying his word is accepted. Since he gets the benefit of presumption of truthfulness, lying is a grave offense.

Plainly this is very different procedure from that of the police court. It is not public. It compels the presence of neither respondent nor witnesses. It has not the sanction of the oath. It does not give the respondent the benefit (if it is a benefit) of silence. It is more like family discipline. But it does substantial justice without publicity. Possibly culprits have escaped by reason of their own false testimony, but in long experience I have never known an instance when I thought the innocent was convicted.

"College Discipline" ordinarily has reference to the corrective action of a professorial operating force upon more or less raw material of students; there is, however, a re-action only to be suggested delicately here. But at times apprentices have been put in charge of our valuable young men, who had less fitness for their job than a wise cattle grower would require for his horses or his steers. They quickly learn, or lost to sight become to memory dear.

More than a hundred years ago, and therefore safe to name, naughty professors Dean and Carter of the University made a raid on the Social Friends' library, and, caught by students of the College were placed in durance, and finally led to their homes by an escort of students, four to each professor. There were breaking of doors, big stick, arrests, but no penalties.

In more recent times an instructor of a little brief authority—we can quote without hestitation an alleged experience so different from that of the rest of us as to be valueless for evidence—announced in the class-room that he had heard that Dartmouth students were a rough set, but that having expected to find some gentlemen among them he had not found one. I confess to a constant and vain regret that some of his hearers who had not yet attained to the stature of perfect gentlemen, did not take him out and stand him on his head in the snow. As a member of the faculty I think I should have voted, "Not guilty, but don't do it again."

In the progress of time nothing has developed in college government so wholesome and genuine as self-control through a representative group. It supplements the power of the faculty at a point of weakness, though I doubt if it ever could or would displace wholly the authority of that body. The intense, absurd, but normally harmless attention paid to freshmen at the beginning of the college year, dangerous from lack of any natural limit in duration or repetition, is, as experience shows, sensibly controlled by a strong group of college leaders. And the same is true of some bad customs that thrive in the dark. Such leaders can give powerful support to honesty in college work. They have checked disorders that threatened to become riots. Mental and moral defectives and those likely to be judged criminals should, it would seem, be left wisely to more mature discrimination.

Opinions concerning the present status of athletics, and of the comparative morality in the College today and forty or fifty years ago are not within the plan and scope of this article.

*This does not refer to the excellent Handbook issued by the D. C. A., which might be called "The Freshman Bible, Jr."

The Tower—out of season

EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72New Hampshire Professor of Chemistry, Emeritus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAthletics in general and football in particular seem to be up for special

March 1922 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE GRANT

March 1922 By JOHN M. GILE '87 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS EXPOSES "FUNDAMENTALIST" MOVEMENT

March 1922 -

Article

ArticleTWELFTH WINTER CARNIVAL A HUGE SUCCESS

March 1922 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

March 1922 -

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB CIRCULAR STIRS EDITORIAL PENS

March 1922

EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72

Article

-

Article

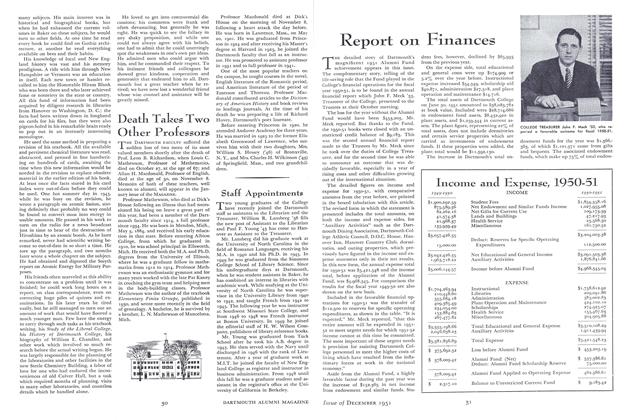

ArticleDeath Takes Two Other Professors

December 1951 -

Article

ArticleA Salute to Hovey

MAY 1964 -

Article

ArticleOver the top

SEPTEMBER 1987 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1937 By Ben Ames Williams Jr. '38 -

Article

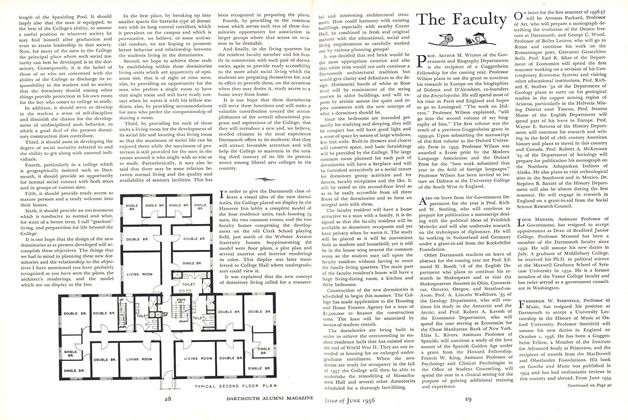

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1956 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

ArticleTo the Class of 1918:

APRIL 1969 By PETER DAVID HOFMAN