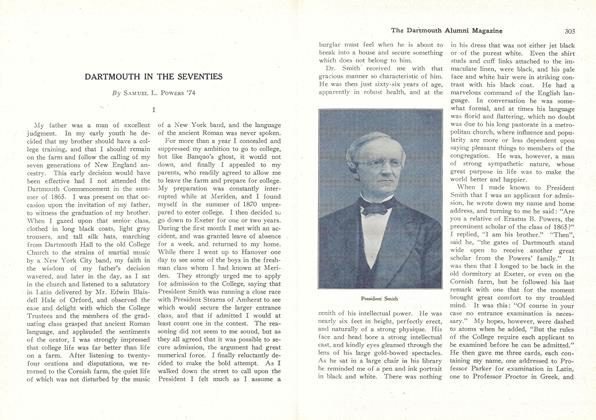

The following article is the greater part of an address by Mr. Powers on the occasion of the annual banquet of the Dartmouth Alumni Association of Boston in Symphony Hall on January 26, 1922. Had space permitted, the alumni would have been interested in seeing the entire address. In introducing his remarks, Mr. Powers made the statement that he had seen one or more members of every class graduating from Dartmouth in the last 105 years. He then mentions specifically Amasa Edes 1817, his father's attorney; Elijah Boardman 1818, the family physician; Ebenezer Carter Tracy 1819, a classmate of Rufus Choate and editor of the "Vermont Journal"; and George Washington Nesmith 1820, a trustee of the College. He then continues:

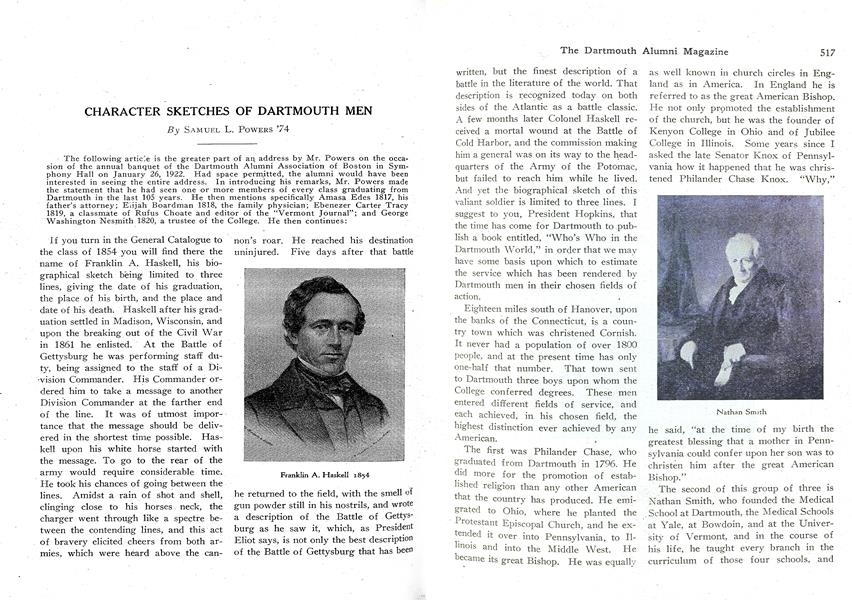

If you turn in the General Catalogue to the class of 1854 you will find there the name of Franklin A. Haskell, his biographical sketch being limited to three lines, giving the date of his graduation, the place Of his birth, and the place and date of his death. Haskell after his graduation settled in Madison, Wisconsin, and upon the breaking out of the Civil War in 1861 he enlisted. At the Battle of Gettysburg he was performing staff duty, being assigned to the staff of a Division Commander. His Commander ordered him to take a message to another Division Commander at the farther end of the line. It was of utmost importance that the message should be delivered in the shortest time possible. Haskell upon his white horse started with the message. To go to the rear of the arm}'- would require considerable time. He took his chances of going between the lines. Amidst a rain of shot and shell, clinging close to his horses neck, the charger went through like a spectre between the contending lines, and this act of bravery elicited cheers from both armies, which were heard above the cannon's non's roar. He reached his destination uninjured. Five days after that battle he returned to the field, with the smell of gun powder still in his nostrils, and wrote a description of the Battle of Gettysburg as he saw it, which, as President Eliot says, is not only the best description of the Battle of Gettysburg that has been written, but the finest description of a battle in the literature of the world. That description is recognized today on both sides of the Atlantic as a battle classic. A few months later Colonel Haskell received a mortal wound at the Battle of Cold Harbor, and the commission making him a general was on its way to the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac, but failed to reach him while he lived. And yet the biographical sketch of this valiant soldier is limited to three lines. I suggest to you, President Hopkins, that the time has come for Dartmouth to publish a book entitled, "Who's Who in the Dartmouth World," in order that we may have some basis upon which to estimate the service which has been rendered by Dartmouth men in their chosen fields of action.

Eighteen miles south of Hanover, upon the banks of the Connecticut, is a country town which was christened Cornish. It never had a population of over 1800 people, and at the present time has only one-half that number. That town sent to Dartmouth three boys upon whom the College conferred degrees. These men entered different fields of service, and each achieved, in his chosen field, the highest distinction ever achieved by any American.

The first was Philander Chase, who graduated from Dartmouth in 1796. He did more for the promotion of established religion than any other American that the country has produced. He emigrated to Ohio, where he planted the Protestant Episcopal Church, and he extended it over, into Pennsylvania, to Illinois and into the Middle West. He became its great Bishop. He was equally as well known in church circles in England as in America. In England he is referred to as the great American Bishop. He not only promoted the establishment of the church, but he was the founder of Kenyon College in Ohio and of Jubilee College in Illinois. Some years since I asked the late Senator Knox of Pennsylvania how it happened that he was christened Philander Chase Knox. "Why," he said, "at the time of my birth the greatest blessing that a mother in Pennsylvania could confer upon her son was to christen him after the great American Bishop."

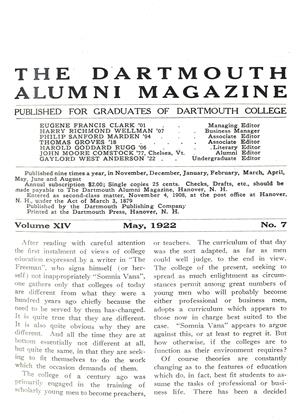

The second of this group of three is Nathan Smith, who founded the Medical School at Dartmouth, the Medical Schools at Yale, at Bowdoin, and at the University of Vermont, and in the course of his life, he taught every branch in the curriculum of those four schools, and was one of the leading lecturers before the Harvard Medical School. Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, in referring to Dr. Smith as an instructor in medicine, says that he did not occupy a chair, he occupied a settee. The history of Nathan Smith's life reads like a romance. At twenty-eight years of age he was following the plow, and became interested in medicine through talking with a country physician, who was ministering to one of the members of his family. He borrowed from this doctor some medical books, and became so interested in the study of the science that he went before the Trustees of Dartmouth and suggested that he would like to establish a medical school in connection with the College. At that time he had never received any medical degree, nor was he licensed to practise medicine, but he so impressed the Trustees that they loaned him the money to go abroad for the purpose of studying medicine and surgery. Later he returned and founded the Dartmouth Medical School in a room in the northeast corner of Old Dartmouth Hall. That room was not a large one, yet it was the lecture room, the laboratory and dissecting room of the new medical school. Later on the College conferred upon him the degree of Doctor of Medicine, and Nathan Smith is- recognized today by the medical profession as having done more for the promotion of medical education than any other American.

The third of this group is Salmon P. Chase, nephew of Bishop Chase, who received his degree from Dartmouth in 1826. He is recognized as the greatest financier this country has produced. After his graduation he went to Ohio, where he achieved distinction in the legal profession, entered public life, was governor of his adopted state, a United States Senator, and later Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. But his great fame will always rest upon the service which he rendered as Secretary of the Treasury under President .Lincoln. When he accepted that portfolio he had no special knowledge of finance or banking. To him it was a new field. The treasury was without money, and its credit was at the lowest -ebb. Obligations of the United States had been protested in New York. The great war was on. Millions of men were to be clothed, fed and equipped, and the duty was imposed upon Chase to formulate a plan by which this tremendous expense could be financed. 1 he lowest rate at which money could be borrowed by the United States was 12 per cent. Chase worked out a theory of finance through a system of legal tender notes, shaped the legislation necessary, and insisted upon and secured favorable action from Congress. He also formulated the method of taxation, and the North was able to secure billions of moey, which maintained the army in the and preserved the union of the States. And what is more, while the war was in progress the credit of the country improved from year to year, and in 1864 the 7 per cent bonds of the United States were selling at a premium. There is nothing comparable with his record as a financier in this country or in any other country on the face of the globe.

In 1810 there came to Dartmouth from the little town of Danville, Vermont, a boy by the name of Thaddeus Stevens. He was the son of a small farmer, and his parents made the supreme sacrifice of their lives to educate the son. He graduated in 1814, and has the distinction of being the greatest parliamentary leader the country has produced, and what is most remarkable in his career is that he won his great fame after he was sixty-eight years of age. He had many of the characteristics of the elder Pitt. Each had great intellectual power and possessed courage of the very highest quality. Stevens became the leader of the war party in Congress by common consent, and he led that party by sheer force of his ability and indomitable will. Mr. Blaine, in speaking of him, says that he never was over-matched in any intellectual combat. He is our great American commoner.

But it is in the educational rather than the political field that Stevens rendered his greatest service to the country. He was the champion of free public education. In the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1834 he secured the enactment of a statute providing for the public education of the poor and the rich alike. Prior to that time the statutes provided for the education of the poor only at public expense; all others secured their education at 'private expense. Mr. Stevens believed that all children should receive elementary education at the expense of the public; that the education of the young was absolutely essential for the stability of government, and that the state provides free public education not as a measure of generosity to its people but for the purpose of educating the public will, and thereby giving stability to government. The Pennsylvania statute of 1834 became unpopular before the end of the year because it imposed upon the taxpayers an additional burden in the way of taxation, and in 1835 there was an organized effort to secure the election of a Legislature that would repeal the Act. It is probably true that at least threefourths of all the members elected to the Legislature of 1835 were committed to the repeal of the Public School Act of the previous year. The repealing act passed the Senate with only eight dissenting votes, and the House was strongly in favor of concurring with the Senate. It is probably true that the greatest speech of Stevens's entire life was that which he made in opposition to the repeal of this Act. At this time he was in the prime of his manhood, — forty-three years of age, — and his speech was of a most masterly character. He characterized the law as "An Act for Branding and Marking the Poor." The effect of the speech was to change the sentiment of the House to an overwhelming defeat of the repealing act and the Senators who listened to that great speech were SO' impressed by it that they returned to their chamber and concurred with the House. No one can estimate the far-reaching influence of that speech upon the cause of free schools in America. Our own McCall, in his excellent History of the Life of Stevens, has portrayed in a most vivid manner this legislative triumph to which I have referred.

Thaddeus Stevens is not, however the only leader of the National House which Dartmouth has given to the Nation. Nelson Dingley of the class of 1855 was the leader of Congress for four years. It would be difficult to imagine two men more unlike than Stevens and Dingley. One was imperious and domineering the other modest and retiring. One possessed forensic ability of the highest order; the other was possessed to a very limited degree of the art of oratory, or that personal magnetism so necessay to leadership. I doubt, however, if any member of Congress was ever better equipped in knowledge of the history and principles of tariff, banking arid curency legislation than Governor Dingley. He was a leader by reason of his profound learning., and stainless integrity. Any statement of fact from him was accepted by both sides of the House as correct. His life furnishes us a splendid example of the power and character of learning over the minds of men.

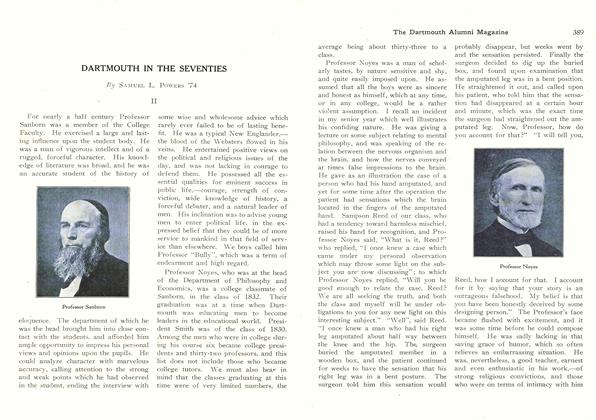

The class of 1855, to which Governor Dingley belonged, graduated Dartmouth's greatest scholar in the person of Walbridge A. Field, better known to us in Massachusetts as Chief Justice Field. Some years ago I called at the Dean's office and said to him that I would like to examine the class room marks of some of the old graduates. What I really had in mind was an examination to ascertain which professor it was who marked ma down in my sophomore year, but as the Dean accompanied me to the basement where the marks, were preserved I had not the courage to call for my own, and I said to him that I would like to look at the marks of Field of the class of 1855, and also those of my brother, who was in the class of 1865, and who also had a high rank. We succeeded in finding the marks of Field for the freshman, junior and senior years, but the marks for the sophomore year were missing. In those days students were marked on & scale of one to five, one being perfect, and two and one-half passing mark. Recitations and examinations were marked separately, the examination mark counting as onequarter in making up the standard of the student. I made a copy of Field's record. In recitation for these three years his mark was one, that is, perfect. In examination for these three years his mark was one, that is, perfect, and I have no doubt that if we could have found the marks for the sophomore year we should have found them to be the same as for the other three years. Certainly no student has ever secured a higher mark. I understand that Harvard has what is called a list of its preeminent scholas, and I am told that at the present time there are sixty-seven upon that list. I have seen two of them. They were both insane. I am going to suggest to you, President Hopkins, that you imitate Harvard in making up a list of Dartmouth's great scholars, and I will say to' you that you need not reserve any space for the class of 1874. That class was a prudent class, and no member took any chance of going insane by reason of over-study. Judge Field at one time was president of this Association, and it was at a time when I was acting as secretary. Now and then I used to call at his house at the South End to talk over matters connected with the Association. One evening I found him reading a Latin book, and he told me that it had been his practice ever since his graduation from college to read either Greek or Latin one hour every day. He asked me if I had ever acquired that habit. I said I had not, but I contemplated doing so. But, upon reflection, when I considered how many habits I had already acquired, it seemed to me better that I should drop some of them rather than add to the number. I doubt if we have had many men in this Commonwealth who knew the literature of the world better than Judge Field. H was a student throughout his entire life, and yet he rarely ever gave the world the benefit of his profound learning. He was a man of great modesty, of high character, an excellent member of our judiciary, and a true gentleman in the highest sense of that term.

I desire to speak of a son of Dartmouth: who was known to you all, and whose love for and loyalty to the College were the predominating traits of his character. I refer to David Cross of the class of 1841. His intense interest in the College no doubt prolonged his life. The year before his death he sent me a written invitation to a dinner which he had planned to take place at the commencement exercises of 1919 in honor of the centennial of the graduation of Choate, and the centennial of the Dartmouth College case. He gave a list of his guests, and said he should then be celebrating the 78th anniversary of his graduation, and should be approaching his 102d birthday. I have no doubt he confidently expected to realize the pleasure of the hope he then entertained. Judge Cross possessed a nature that had in it much of the dramatic. If he had gone on the stage he would have made a great actor. Those of you who saw him in Webster Hall on a Dartmouth Night could not have failed to be impressed with his exceptional dramatic power. As he stepped to the extreme front of the stage and received the tremendous applause which greeted him he was absolutely unmoved, and when he raised his hand as a signal for silence you saw as fine a piece of acting as you could expect to witness on the stage. When he had secured silence he said, "I have been here before." Then came another burst of applause, and when he had secured silence he followed it with the laconic sentence, "I expect to be here again." I remember many years ago he attended a banquet of this Association, and in his speech he said, "I see here many that may not be visible to you," and then he proceeded to name fifteen or twenty of our distinguished alumni who at that time were in the unseen world, and he placed them at the table, commenting upon each one, and he peopled the room with the spirits o the departed. No one but a great actor could play such a part. In the later years of his life he lived over the scenes of his childhood, and his school days. Every member of his class remained vivid in his memory. When he came back to Hanover he was like old Colonel Newcomb, so beautifully portrayed by Thackeray, who came back to the old school to live over the .life of his school days. As an honorary member of many a graduating class his memory will be long preserved by the Dartmouth,alumni.

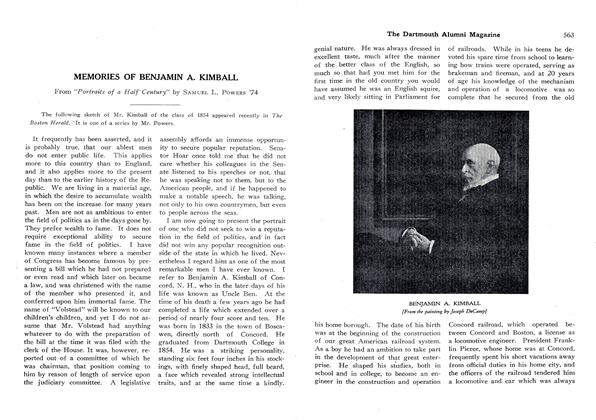

For my last sketch I am going to portray the character of one who but recently reached the end of life's journey, and who measured by any standard 'was among the very best that the Old Mother has given to the service of mankind,— Benjamin A. Kimball of the class of 1854, or "Uncle Ben" as he was best known to his friends, was a very remarkable man. His keen intellect, far-reaching sagacity, and indomitable perseverance .would have won for him distinction in any field of action. He possessed in a remarkable degree the best traits which go to make up the typical Dartmouth character. His love for the College was intense, and the service he rendered his Alma Mater was of the greatest value. During his long life he was a great traveler. Every journey he made was of educational value to him, because he studied the customs and the manners of the peoples whom he visited. Many years ago while he was making a journey around the world he reached Cairo and made the trip up the Nile. While on the boat he was taken ill, and he made a landing at an English hotel located on an island in the river, and before the night was over he was stricken with pneumonia. Mrs. Kimball became exceedingly alarmed. She was not quite satisfied with the hotel physician, and she learned that Sir James McKenzie, at that time physician to Queen Victoria, was sojourning at the hotel, and she requested the attending physician to call Sir James into conference. This he declined to do, saying that it would be highly improper to make that request; that Sir James was taking his vacation, and under no circumstances would it be proper to ask him to take part in any professional duty. Mrs. Kimball's anxiety was such that she decided to have a conference with Sir James. She told him that she was an American, that her husband was seriously ill, and that she was in great distress, and Sir James said, "I will do everything I can to relieve him," and he took charge of Uncle Ben, and remained with him day and night throughout his illness, staying in the room almost constantly. When Mr. Kimball was convalescing Sir James said to him, "You are the toughest old fellow I have ever seen. The amount of medicine I have given you would have killed at least ten Englishmen. I have secured from my attendance upon you some very valuable information by reason of the tests I have made which I would never have made upon one of my own countrymen. They will be of great value to me in the years to come." From that time on Sir James McKenzie and Mr. Kimball became close and intimate friends. I have seen letters which the distinguished English physician wrote to Uncle Ben, in which he said, "When you next come to London if you do not come directly to my house I will never forgive you," and it was through that acquaintance that Mr. Kimball came to know a very large number of distinguished Englishmen.

There is one other incident in the life of Mr. Kimball that to me has always seemed exceedingly interesting. Many years ago Mr. Kimball made his first trip up the German Rhine. As he sat upon the steamer's deck viewing the vineclad slopes on either side of the river, he finally came into view of the castles built by the Barons of the Middle Ages and located on the highest parts of the land on either side of the river. It was then that the thought came to him that he would like to build a castle similar to those, upon a promontory which he owned on the southerly bank of Lake Winnepesaukee; and so he made a landing, secured an architect, and arranged with him to make plans for a castle which suited his fancy. Later on he reproduced that castle, which stands today some seven hundred feet above the waters of Winnepesaukee Lake, on the southerly shore, and which is known as "Kimball's Castle." That castle is an exact reproduction of the one that he selected upon the banks of the Rhine. My belief is that the most joyous hours of his life were those spent during the summer season at his New Hampshire castle. I have seen Uncle Ben many times sitting in a large chair upon the broad veranda looking out through the arches at the view before him, and on one occasion he said to me, "Where in the world can you find a more superb view, one that has greater diversity of scenery, than the one which lies before us?" Arid it was a remarkable view,—seven hundred feet below were the sparkling waters of Winnepesaukee, dotted with its hundreds of islands, each rich with summer verdure extending to the very water's edge, and farther to the north were the silver waters of Lake Asquam, hedged in by that beautiful range of mountains,—Chocorua, Passaconaway, Whiteface and Sandwich Dome,—and then still farther to the north the Presidential range,—Mount Washington piercing the fleecy clouds. Farther to the west, Lafayette and Lincoln and Moosilauke, and still farther to the west the mountains of Vermont, while to the east, beyond Ossipee, were the mountains on the westerly line of Maine, and to the south Belknap and Gunstock, as though keeping guard over the castle. Upon that broad veranda Uncle Ben would not only discuss the beauty of the scene, but his breast swelled with pride as he recounted the history of New Hampshire and the history of the old College. His life, which extended over a period of nearly four-score and ten years, was one of useful service to the State and the College.

The few characters I have sketched this evening possess the characteristic traits of those sons which Dartmouth has been sending forth to the world during the last century and a half. In the century and a half to come, it may be in many centuries to come, the old College will continue to send forth her sons to render loyal, faithful and useful service to mankind.

Franklin A. Haskell 1854

Nathan Smith

Salmon P. Chase 1826

Thaddeus Stevens 1814

Walbridge A. Field 1855