It is safe to say that nothing in the recent history of Dartmouth College has been so widely noted in newspapers and magazines in the United States and in Canada as the address delivered at the opening of College by President Hopkins in which the President declared that more men than the colleges of the country could properly accommodate and instruct were desirous of becoming college sudents and that "there is such a thing as an aristocracy of brains made up of men intellectually alert and intellectually eager to Whom, increasingly, the opportunities of higher education ought to be restricted...."

On the basis of newspaper and magazine clippings already received (and those from more remote sections of the country have barely begun to appear here) the President's opening address and the comments upon it may be said to have set a record in "publicity" which the football team, though it should go through the present season without a defeat, would do well to equal.

In addition to the amount of newspaper space given to the address itself, from verbatim accounts to ten line "boxes," more than a hundred editorials upon the subject, to say nothing of symposiums and the notes of columnists and paragraphers have been received from cities and villages throughout the United States, and from Manitoba, Ottawa, Toronto, and Montreal.

In the main the editorial comment has been of a favorable nature, though many writers expressed doubt as to just what President Hopkins meant, and others, conceiving that by the theory of democracy everybody is entitled to everything whether or not he is qualified to receive it, flew into tantrums over the word "aristocracy" and will scarcely yet have recovered.

The ALUMNI MAGAZINE cannot attempt to reprint more than a small portion of the bulk of editorial comment, and the following extracts have been selected more or less at random in an effort to convey merely an impression of the various types of reaction.

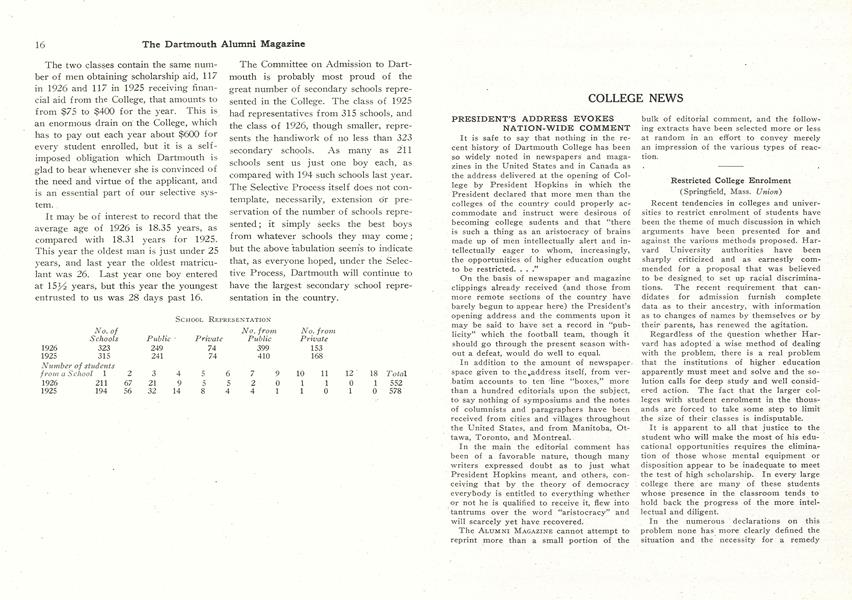

Restricted College Enrolment

(Springfield, Mass. Union)

Recent tendencies in colleges and universities to restrict enrolment of students have been the theme of much discussion in which arguments have been presented for and against the various methods proposed. Harvard University authorities have been sharply criticized and as earnestly commended for a proposal that was believed to be designed, to set up racial discriminations. The recent requirement that candidates for admission furnish complete data. as to their ancestry, with information as to changes of names by themselves or by their parents, has renewed the agitation.

Regardless of the question whether Harvard has adopted a wise method of dealing with the problem, there is a real problem that the institutions of higher education apparently must meet and solve and the solution calls for deep study and well considered action. The fact that the larger colleges with student enrolment in the thousands are forced to take some step to limit the size of their classes is indisputable.

It is apparent to all that justice to the student who will make the most of his educational opportunities requires the elimination of those whose mental equipment or disposition appear to be inadequate to meet the test of high scholarship. In every large college there are many of these students whose presence in the classroom tends to hold back the progress of the more intellectual and diligent.

In the numerous declarations on this problem none has more clearly defined the situation and the necessity for a remedy than President Ernest M. Hopkins of Dartmouth College in his address at the opening of the academic year. He said in part:

"This is a twofold necessity; on the one hand that men incapable of profiting by the advantages which the college offers, or indisposed to do so, shall not be withdrawn from useful work to spend their time, profitlessly in idleness, acquiring false standards of living; and on the other hand that the contribution which the college is capable of making to the lives of competent men, and through them to society, shall not be too largely lessened by the slackening of pace due to the presence of men indifferent or wanting in capacity.

"Too often men reputed to be seeking an education are only seeking membership in a social organization which has a reputation for affording an education."

Repudiating as "incompatible with the conceptions of democracy any assumption that the privilege of higher education should be restricted to any class defined by the accident of birth or by the fortuitous circumstance of possession of wealth," President Hopkins urges the recognition of an "aristocracy of brains, made up of men intellectually alert and intellectually eager." This declaration by the president of Dartmouth presents the case in a manner that leaves little room for cavilling at selective measures as conducive to the setting up of an un-American aristocracy in education and will place the essentials of the problem and its proper solution before the people in frank and understandable terms.

College Admissions

(Dayton, Ohio, News)

The principle which Arthur Morgan president of the Antioch college at Yellow Springs has injected into the institutional program there, seems to have been followed to some degree by president E. Ml Hopkins of Dartmouth college. There are, of course, some differences in the views of the two men. Mr. Morgan is planning to make of Antioch a "finishing school" for the students who matriculate there. Dr. Hopkins is working on a somewhat different theory. In both cases, however, there seems to be a disposition to offer college careers only for those who are apt to make use of the knowledge they acquire within the institution. President Hopkins is quoted as saying that too many men go to college. President Morgan has not said anything like this. He is quoted at various times as saying, however, that too many young people enter college and do not acquire that depth of training and that necessary practical experience which are so essential to successful industrial and commercial life. President Hopkins regards education as a privilege. It certainly may truthfully be so designated. But it is more than a privilege. It is an opportunity. This is President Morgan's theory. Both men, in fact, seem to be working to the one end—that of impressing upon the minds of young people that going to college carries with it certain fixed and important obligations.

Every young man and woman in America who honestly desires to acquire a first rate education, and aspires to use that knowledge in a betterment of human conditions or an improvement in industry or art, ought to be afforded the chance. It ought to be possible for universities to . accept such young people, whether they have the money with which to pay their expenses or not. Unfortunately college treasuries are not limitless. The Utopian age has not been ushered in. But the election of students, as advocated by Mr. Morgan and now seconded by Dr. Hopkins, is coming to be more understood as essential than ever before. Men and women who go to college to join a fraternity or to while away their time have no place in the program. Let them become producers rather than drones. They may very well be eliminated from admission to active college life. In this respect Dr. Hopkins stands on undebatable ground. It is interesting to observe the similarity in views between the two college heads—Morgan and Hopkins. They have much in common though, perhaps, an analysis of their positive views might disclose that so far as their theories are concerned they are as separated as the two poles.

Democracy and the College

(New York Globe)

The debate started by President E. M. Hopkins of Dartmouth concerning an aristocracy of brains is provoking many to speech. Dr. Josiah Penniman, acting provost, spoke in behalf of the so-called "open door" policy at the formal opening of the University of Pennsylvania last week. The Philadelphia educator was heralded as an opponent of President Hopkins' teachings. Acually they were talking of different aspects of the question.

The Dartmouth leader would exclude those who are unfit for college. He specifically said that the tests to be imposed were intellectual and not financial or social. The Pennsylvania spokesman protested very properly against any proposal "to shut the door in the face of the eager, aspiring, earnest youth who has set his heart on coming to college and who is of good character and who had qualified academically." President Hopkins made it plain in his original address that he favored just such a policy.

It is fortunate for the colleges and for the country that the discussion should have been started. It ought to be continued, because it goes to the heart of the problem of democracy. The widest spread of education is essential to the success of popular, government. Jefferson realized that, and for this reason he counted his part in founding the University of Virginia his most memorable service. It is safe to say that from the point of view of the nation it would be best to have every voter a college graduate. It is not possible to bring too much trained intelligence to bear upon public questions. Education alone will not save democracy, but without the enlightenment which comes from study and books popular rule is like an unassisted blind man trying to cross a congested street.

From this standpoint every boy and girl capable of taking a college education ought to be given the privilege. Money ought not to be the test. The nation, for its own sake, must see that poverty dims the vision of none of its citizens. But this is just onehalf of the picture. Educators know that an uncertain number of boys and girls who now go to college are unfitted naturally for the experience. A rich man's son ordinarily is sent to college, regardless of his mental equipment. A poor boy is less apt to go unless he has shown special abilities.

The truth to which President Hopkins referred is that fitness for college does not go with wealth or social status. Capacity to profit by what the colleges offer varies like stature or the color of the eyes. The duty of educators and of the public which supports colleges is to teach all who are teachable, and not to deform the educational process by permitting the unteachables to clog the institutions. If the gentlemen who are now directing higher education in this country can awaken the nation to this necessity they will have done well.

Dartmouth's Idea

(Charlotte, Mich., Tribune)

At the opening of the one hundred and fifty-fourth year at Dartmouth College, President Ernest M. Hopkins declared in an address to the student body that the opportunities offered by a college education are definitely a privilege and not a universal right. At the first glance this may come as a rude shock to the American who believes that as a land where opportunities are supposed to be equal a college education should be open to every man or woman who wants it.

In defending his position, the president of Dartmouth said that strict entrance requirements were necessary because of a two-fold necessity: "On the one hand that men incapable of profiting by the advantages which the college offers, or indisposed, shall not be withdrawn from useful work to spend their time profitlessly, in idleness, acquiring false standards; and, on the other hand, that the contribution which the college is capable of making to the lives of competent men and through them to society shall not be too largely lessened by the slackening of pace due to the presence of men indifferent or wanting in capacity."

Here Dr. Hopkins has put the matter up squarely and fearlessly. There is no sense in dodging the issue that college is not meant for all the young men. The Dartmouth president is right in" saying, as he does further in the address that many men go to college for the social standing it will give them. Dr. Hopkins' idea is that college should be open only for those men who desire college for the work they can accomplish and who are capable of doing this work.

Only in this way can the colleges retain their high standard. As he says, the dull or lazy student will slow the pace of the whole institution. His plan is to keep the personnel of the college small, of picked men, so that the college, the men and society will profit most.

The idea may seem mercenary, but if carried out rightly there is no doubt about the type of graduate any college will turn out. For the good of the colleges and society there have been too many who did regard their college as merely a great social trademark.

An Aristocracy of Brains

(Richmond, Va., Dispatch)

When Dr. Ernest M. Hopkins, president of Dartmouth College declared in his opening address that college education should be reserved for "an aristocracy of brains," he hurled a boomerang which is extremely liable to return and strike him on his learned pate. Already educators the country over are engaging in the heated discussion caused by Dr. Hopkins' statement. They are willing to admit that too many unqualified men go to college, but that they should recognize "an aristocracy of brains" is another matter entirely. Dr. Elmer Ellsworth Brown, chancellor of New York University, in replying to Dr. Hopkins, asserts that the "point of saturation" in American colleges is still a long way off.

At the present time college trained men and women form approximately three per cent of the population of the United States. Dr. Brown believes that ultimately ten per cent of the people will have a higher education. That leaves something like eight million persons yet to enjoy the privileges and benefits of college life. There are too many college students only when their mere numbers prevent them from being properly instructed and from receiving all the culture and training which are due them. Institutions of learning that are overcrowded certainly cannot perform the services expected of them by society; they cannot fulfill their missions or live up to their highest ideals.

To say that college education should be reserved for "an aristocracy of brains" is to use an unfortunate expression. It denies to the vast majority of the people the right to an equal chance. It departs far from the doctrines of Jefferson and Lincoln, who held that it was the duty of the country's educational system at least to start the youth of the land upon a footing of equality. What this country needs more than "an aristocracy of brains" is the elimination of the tendency to discriminate which has been observed in some of our leading colleges. The acquisition of "brains" should not be restricted to the few who can answer Mr. Edison's questionnaire or explain Professor Einstein's theory of relativity or give the history and properties of the fourth dimension.

Too Many College Misfits

(Philadelphia, Pa., Record)

The resumption of studies at Dartmouth College has been marked, for several Septembers, by the delivery of words of true wisdom in the opening greeting of the president to the undergraduate body. Dr. E. M. Hopkins this year surpassed himself; and the views to which he gave eloquent expression cannot help but arouse interest far beyond the classic confines of Hanover, N. H.

Dr. Hopkins says that too many men go to college. He goes even farther than that and declares that "the opportunities for securing an education byway of the college course are definitely a privilege and not at all a universal right." This may sound to some like rank snobbishness, but it is nothing of the sort. There is a basis of good common sense in it. Funds for the support of higher educational institutions are not limitless, either from public or private endowments. It becomes necessary, therefore, says Dr. Hopkins, "that a working theory be sought that will operate with some degree of accuracy to define the individuals who shall. make up the group to whom, in justice to the public good, the privilege shall be extended, and to specify those from whom the privilege should be withheld. He expressly deprecates any test of birth or wealth in the selection of the favored ones, but he does insist that there is such a thing as "an aristocracy of brains, made up of men intellectually eager and alert—if democracy is to be a quality product rather than simply a quantity one, and if excellence and effectiveness are to displace the mediocrity toward which democracy has such a tendency to skid."

It takes courage for a college president to speak thus frankly in the presence of a body of young men standing at his threshold—although he may feel assured, as most other college presidents are, that a large percentage of those neoephytes have no business to be there. It is unfortunately true, as Dr. Hopkins very plainly went on to say, that too many youths who go to college "are only seeking membership in a social organization which has a reputation for affording an education, from which reputation they expect to benefit, if they can avoid being detached from the association." Entirely too many youngsters go to college because it "is the thing," because their fathers can afford it, or for any number of other reasons but the right one.

Dr. Hopkins speaks good, sound, sense. He is not an intellectual snob, but an intellectual democrat, for if the "working theory" for which he seeks ever attains the desired perfection it will be most helpful to the poor boy with brains who is eager for an education.

A Suspicious Educator

(Philadelphia, Pa., Eve. Ledger)

It is at least charitable to assume that Ernest M. Hopkins, president of Dartmouth, was not giving accurate expression to his thoughts in his statement that "too many men are going to college." Similarly infelicitous is his appeal for an aristocracy of brains and his assertion that "college courses are definitely a privilege and not at all a universal right."

This educator is obviously vexed by the trials of attempting to intellectually invigorate young men who react but indifferently to the process. There are numbers of these in all universities, but admission of that generally known fact hardly is proof that higher education on a broad and generous scale is a failure.

To condemn liberal opportunities for college education because of a certain proportion of misfits is in theory like stigmatizing the entire human race because some unworthy specimens of it are to be found.

It was perhaps Mr. Hopkins' intention to impress upon new students at the opening of the academic year in the New Hampshire college the necessity of realizing their responsibilities. If anything else was deliberately designed, the president. of Dartmouth has been guilty of one of the most offensive pleas for snobbery and intellectual superciliousness ever voiced, by an American educator in a high office.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

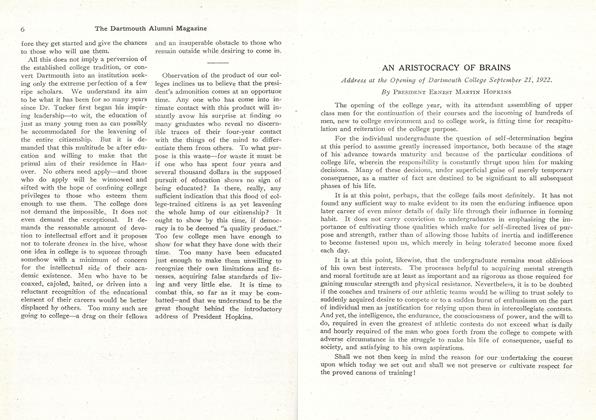

ArticleAN ARISTOCRACY OF BRAINS

November 1922 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleIt is hardly to be conceived that a magazine devoted primarily

November 1922 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1926

November 1922 By E. GORDON BILL -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

November 1922

Article

-

Article

ArticleForeign Study Grants

JUNE 1959 -

Article

ArticleHALF WAY THERE

December 1990 -

Article

ArticleThe Time Allotted Us

June 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleDoctor of Laws

August, 1926 By JAMES THOMSON SHOTWELL -

Article

ArticleA DECADE OF RENEGING

February 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Arms Race and the Life of the Mind

APRIL 1983 By Stephen J. Nelson