Address at the opening of Dartmouth College, September 17, 1925

It is a familiar habit of men interested in a common purpose periodically to get together and to seek understanding of their common problems. So we gather today, reassembled for the beginning of a new college year, and again giving our attention to college purpose.

Edmund Burke has stated that civilization is a contract among the great dead, the living, and the unborn. May it not be added that education is consideration of how this contract may be kept. The scope of education embraces alike knowledge of the past, understanding of the present, and speculation about the future.

I have before me a letter from a friend, a perspicacious and successful man of large affairs, written in regard to his son. He says, "I am, of course, happy in the thought that my boy is to get what I missed. I would be doubly happy if I could overcome the age-long impossibility,—the inability of the old to transmit their experiences to the. young,—and insure that he would avail himself to the full of his opportunities."

I think that no college officer worthy of his calling is ever unconscious of the great cloud of witnesses with which the college is compassed about, nor ever quite forgets those encircling rows of parents, eager in behalf of their sons for all good things and suffering vicarious pain as youth in its heedlessness incurs penalties and suffers hurt which might have been avoided.

I say this in spite of occasional vexations at the attitudes of members of the older generation. Two college presidents were once discussing the ideal student body. One said that he would like a college made up of orphans wherein there would be freedom from the unintelligent interference of parents. The other stated preference for a college of jailbirds wherein there would be no pride of association which would lead to alumni organization. I refer to this point of view merely with an eye to the future, since many of you will become parents and a somewhat lesser number, alumni.

Returning to seriousness, however, the present generation of college men is entitled to knowledge of the fact that they are better men than generations which have gone before, so far as sins of commission are concerned. Because of this very fact, however, their sins of omission call for graver censure and they are to be held as more blameworthy for wasted privileges. It ought to be that educational opportunity should be more eagerly sought and more largely utilized by the present generation than by any previous one, not only because of the need of society that this should be done, not only because of the greater facilities by which it might be done, but also because of the greater capabilities with which the college student of today is endowed as a result of experience and environment and because of general welfare among the American people.

The danger existent in the situation looms constantly, that in the fullness of life and in the variety of interesting things which impinge constantly on the consciousness of man from earliest childhood, no time nor interest will be left available either for the great dead or for the unborn. Hence results concentration of interest upon the present. The too frequent result of such a state is fatuous egotism and stultifying selfishness. These work themselves out in a distasteful philosophy and claim for themselves a selfindulgence which they prettily phrase as self-expression.

No generation, not even one with the wealth of resources of our own, is enough self-sufficient to disregard the experiences of mankind through countless centuries past. No generation is yet existent which can logically consider itself as representing the full flower of realization of the possibilities of man. It is the function of the college among many other things to make these facts clear, that we may understand that we do not live to ourselves alone, that in the long race of progress, the lives of those from whose hands we have received the torch of civilization are as important as are ours, and that responsibility to the future cannot be evaded by disavowal.

Among the many aims common to education and to religion is the abundant life. The great Teacher said that he came that the world might have life, and have it abundantly. This is the great objective of the college, and towards this all its avenues ought to be opened, and in these avenues ought to be heard the marching feet of all its students. By so far as the college falls short of securing this result, by so far it falls short of reaching its goal,- and by so far the nonparticipating men of the college fall short of complete living. .The point needs constant reiteration because the period of the college course is the only period from college entrance age on when a man is largely free to seek the abundance of life. It is no rhetorical phrase to say that the opportunities which are available within the college are not in the life of the average man ever duplicated again.

No people have ever lived so abundantly as did the Greeks. The result was that they made contributions to civilization such as have been made by no other people at any subsequent time, and that they live in the memories of mankind eternally. Their military men were men of letters, their statesmen were poets, their scientists were philosophers. Their sculptors finished the parts of statues which were not to be seen as carefully as those portions to be exposed to view. They worked for the love of the working, to their own great satisfaction and to the benefit of mankind through all the ages.

Surely, the man who wishes to enrich his own life cannot afford to be ignorant of such men of ancient days. Neither can he allow himself to be ignorant of the fact of the enlarging universe wherein, on the one hand, we invade the vast and, on the other, the minute, and progressively with greater knowledge.

Probably no experienced man in college work is unconscious that the American college has other aspects and other attributes than those pertaining purely to scholarship. Nevertheless, it is not easy for college officers, acquainted with the need of the world for men who can live abundantly, to sit by without protest and to see men capable of qualifying for such a life frittering away their time instead, or giving minds potentially strong to pusillanimous efforts for the accomplishing of inconsequential things. Let us make no mistake. If terms like "littleness" or "narrowness" are to be applied, they are apt for the man who has objection to the protest more than to him who makes it.

Now, in regard to the college, there are certain conditions about which we ought to have common understanding.

It has not infrequently been shown that the progress of the world is dependent upon men who are capable of seeing familiar things with a detachment which reveals unfamiliar features. Let us reexamine this "going to college" upon which we have embarked and which is the conventional thing for the American boy to look forward to and to desire.

No people has ever undertaken the experiment of education on so vast a scale as it is being developed in the United States at the present time. Never, in the history of mankind, has the scope of education been so broad or have the facilities for enhancing its effectiveness been so plentiful. Never has wealth been given so generously knd so continuously to a single cause. Never has the number ot men been so great who have consecrated their abilities, their careers, their lives, to contributing to this great service. The agencies for making education available, therefore, have become many and accessible, but unfortunately, education does not inevitably thereby become more widespread nor more complete.

There was an old-time query whether sound existed if it was not heard. A life question may well be considered amongst us, whether an education exists if it is not accepted. Likewise, we should add the query if it can be effectually received if it is not sought.

Making specific applications of these assertions, the further accomplishment of Dartmouth College as an institution for higher learning at this particular time is dependent upon the attitude of the undergraduate body here gathered.

Commodious buildings, capable m structors devoted to the interests of scholarship, traditions, atmosphere, all necessary to the college which would be great,—are contributory to, but do not assure education. The fulfillment of the educational ideal of the college can only be attained by the presence of an eager, intellectually serious, and industrious group of men as students within the college. These statements are no less true because trite. Moreover, they have never been given so much recognition by the undergraduate college as to make repetition seem superfluous.

Unfortunately, we have to conclude that the vast extent of the present-day zeal for going to college is not indicative of any like increase of zeal for education. Quite the contrary!

I am sometimes reminded of an assertion once made to me by a diet specialist of large and remunerative practice. He said that among his women clients there were always a considerable number who, after much painstaking in seeking advice, and after the payment of generous fees, yet felt that the results of a periodical indulgence in a dietetic orgy was a good joke on the doctor. Analogous reasoning in regard to college prescriptions has not been unknown about this campus.

Whatever its advantages, the prevalence of the habit of seeking a college degree as this disadvantage, that it no longer is a romantic adventure, with the appeal to the imagination that it had formerly. So, becoming the natural thing to do, it is done in many an instance casually, without over-much consideration as to why it should be done and without particular appreciation of the privilege of doing it. The fact is that the old-time desire for the distinction of a college degree has been replaced in the case of many a man by the desire to avoid not having one, with the result that an active stimulus has been replaced by a passive one.

The number enrolled in the membership of American colleges and universities today is almost as great as the number of all who- have been graduated from all American institutions of higher learning since the founding of the oldest in 1636.

Fifty years ago there was no college in America with a total undergraduate enrollment greater than what will be the enrollment of the freshman class now entering Dartmouth.

These facts are not irrelevant to consideration of those undergraduates who strive to understand the problem of the college of today. Fortunately, there are many of these. The college would be largely futile if it were not for the large number in its membership always who have understanding and purpose.

It would, on the other hand, achieve unprecedented results if the unthinking group could be replaced or could be induced to seek understanding of what education is and what it is capable of doing for a true disciple.

In the large, understanding is the vital quality needed not only in regard to the problems of education, but in regard to all problems of life. Education is learning to understand, and he who has acquired understanding is educated.

It is as true today as it was in the days when the Book of Proverbs was written that knowledge and wisdom are incomplete without understanding. No fact is of much consequence ultimately except in relation to other facts. It may truthfully be claimed, unfortunately, that faculties and administrations in colleges and universities fail as completely in recognizing this as do undergraduates; nevertheless, the need for understanding in one group is not abated, because of the lack of this quality in another.

If all men of great knowledge had understanding, the establishment of pervasive educational ideals within this country and elsewhere would be a far simpler task. Arrogance, superciliousness and indifference are not infrequently associated with technical knowledge, but they are impossible in the man who has understanding, the fruits of which are humility and a spirit of neighborliness.

The most important question involved in the Tennessee trial of this summer was not the right of a legislature to deny to children of its state the modern theories of leaders of scientific thought. It was a question, rather, in regard to the right of these men of learning to remain indifferent to public ignorance and to refuse to assume any responsibility for interpreting to men not technically trained what men of science have believed and why they have believed it. Even if the attempt to do something of this in the trial had been successful, its influence could not have offset the long period of superciliousness which has characterized the attitude of many a man of scientific attainment towards those who were not of his cloth.

Unfortunately, for educational progress, dogmatism and bigotry were the exelusive attributes of no single camp in the issues which led up to this trial!

It is incumbent upon those having access to educational opportunity in their youth to reflect upon the fact that the possibilities of adult education are largely within unexplored territory, but that it is territory which democracy must claim and must occupy with educational leaders of understanding hearts and minds before democracy can be healthful or even safe. Certainly, in the development of this field there will be little place for men of knowledge who have not learned humility and who cannot forego the patronizing attitude towards men of lesser distinction, even when their attainments are less because of lesser opportunities.

The fact seems to be that educational opportunity was so long confined to members of privileged classes that the usages of those times still restrain and restrict men in the methods which they feel free to adopt, even when most democratically inclined.

The theory of an aristocracy of brains is fallacious if it starts with any assumption that brains are exclusively the possession of any formal group whether defined by birth, worldly possessions, social station, or even previous association with a formal institution of learning. The theory has justification only if brains are to be paid deference wherever found.

It is not well to blind ourselves to the weaknesses of official college organization even though we do not know how to correct them. The college process is admirably adapted to imparting knowledge. It has some effectiveness in cultivating intelligence. It does little towards cultivating understanding of the interrelations of facts and of the unity of knowledge. This therefore has to be left to the self-education of the student, without the spirit of which none of the college contribution is of much worth.

The increasing discussion as to the merits of democracy as a principle and the obvious swing away from it as a practice in governments make it, day by day, more important that we understand it and its implications.

If the principle is right it should be adhered to. If it be wrong it should be rejected. Surely it would be mentally stultifying to profess democracy on the one hand, while on the other we accepted and worked toward a code of autocracy. The procedures of democracy have already advanced far beyond the influence of education to guide these. It is not unlikely that the generation of men now in college will be called upon to make vital decision whether the influences of education shall be far extended beyond anything that we now know or whether the practice of democracy shall be radically curtailed. There are many arguments to substantiate both positions. May men of your time prove competent to pass understandingly upon them.

There would be little point in emphasizing these rather self-evident statements at this time except for the fact that the acquiring of understanding which shall lead to a philosophy of life is dependent on reflection. This requires leisure, and leisure is available in a college course to a degree seldom found afterwards.

It is too little considered how greatly the background of life has been transformed even within the period of the youngest member of the College. Conditions have changed the nature of the home. The population of the country has become preponderantly an urban population and is on its way to becoming overwhelmingly so. Government has been removed from local centers and centralized to unprecedented degree. The adaptations of invention have largely increased the range of contacts of human beings and have added enormously to the interest of life, whatever have been their effects upon its satisfaction. Along with all these, everybody's expressed thoughts have become available to everybody else, until the intellectual ether has become as badly jammed as is ever the physical ether. We need a selective process for identifying good ideas even more than for choosing desirable freshmen.

A great manufacturer, given to philosophical generalizations in regard to life and its affairs, said this summer that one of the great troubles of the world is too many books and too many people reading them. His assertion at least has the justification that it is not yet clear that men increase their mental stature more by reading vast numbers of books than they did formerly by reading more reflectively a few. selected books. Absorption of the thoughts of others may be carried to the point where no time is left for developing one's own power to form opinions.

Let us be mindful, in this life of ours together, that for a time we have the opportunity to be thorough and let us strive purposefully to avoid the superficiality which accepts information but never understands.

Cultivation of the ability to organize one's own use of time may seem some- what afield from the problems of education, but I am persuaded that nothing is more vital. Herein we approach a question of adjustment which is peculiarly the student's own, for college regulations or college machinery can do little with it or about it. The pace of the: distinctly scholastic work is not swift enough nor are the college requirements so exacting that there is not left a comfortable margin of leisure time for the man who properly arranges his work. The profit of his college course may be immeasurably enhanced herein. At any rate, it behooves the college man not lightly to mortgage his leisure without knowledge of what use of it would give him greatest satisfaction now and in succeeding years.

Finally, the desirable effect of college associations has never been better stated than by President Hyde, when he said:

'"To be at home in all lands and all ages; to count Nature a familiar acquaintance, and Art an intimate friend; to gain a standard for the appreciation, of other men's work and the criticism of your own; to carry the keys of the world's library in your pocket, and feel its resources behind you in whatever task you undertake; to make hosts of friends among the men of your own age who are to be leaders in all walks of life, to lose yourself in generous enthusiasms and cooperate with others for common ends; to learn manners from students who are gentlemen, and form character under professors who are cultured,—this is the offer of the College for the best four years of your life."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICAL FITNESS

November 1925 By W m. R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Article

ArticleHere Begnneth another year

November 1925 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1925 -

Article

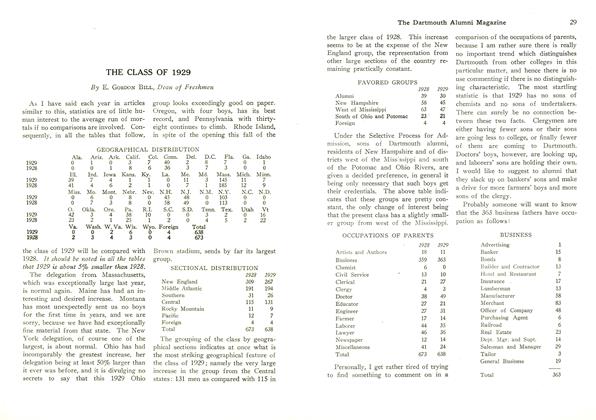

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1929

November 1925 By E. GORDON BILL, Dean of Freshmen -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November 1925 By Franklin Mcduffee, Frank Maloy Anderson -

Article

ArticleSOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ASSOCIATION

November 1925

President Ernest Martin Hopkins

-

Article

ArticleSOME ATTRIBUTES OF UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION

November, 1924 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleSHOULD COLLEGES BE EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS?

MARCH, 1928 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleAttributes of Vision: The Baccalaureate Address

JULY 1931 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins

Article

-

Article

ArticlePROF. HOLDEN RESIGNS THAYER SCHOOL DIRECTORATE

February 1925 -

Article

ArticleWith the D. 0. C.

April 1939 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

MAY 1959 -

Article

Article1963 ENROLLMENT

NOVEMBER 1963 -

Article

ArticleGIVE A ROUSE TO REUNERS

SEPTEMBER 1997 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

April 1916 By Gray Knapp '12

President Ernest Martin Hopkins

-

Article

ArticleSOME ATTRIBUTES OF UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION

November, 1924 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleSHOULD COLLEGES BE EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS?

MARCH, 1928 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleAttributes of Vision: The Baccalaureate Address

JULY 1931 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins