By Mark A. Smith '10. Publications of the Institute of Economics. The MacMillan Co. New York, 1926.

Among the many important problems to which the war and the post-war period have directed the attention of American business men and professional economists as well as to a much greater degree than ever before are the problems connected with international commercial policies, and among these commercial policies, the tariff, the most important of our trade policies, has received renewed attention and examination. Of the groups of economists who have been especially prominent in studying these commercial problems, the Institute of Economics probably deserves first place. This study, The Tariff on Wool, is one of a series which the Institute is presenting dealing with the relation of the tariff to particular lines of production in the United States. In this series dogmatic theorizing in regard to protection is set aside, and an attempt at a dispassionate investigation of the concrete effects of tariff legislation on particular industries from the point of view of public welfare is made.

This study of Mr. Smith's is unusually timely, for, in addition to presenting the results of careful investigation dealing with the effects of one of the most highly controversial the tariff schedules, it is also a study in agricultural problems, that much discussed but nothing done about problem which is rearing its head to disturb the peace of many of our statesmen.

Mr. Smith's study is divided into three parts: The Sheep Industry in the United States and Foreign Countries; History of Wool Duties in the United States; and The Present Problem.

In the first part of the study a brief history of the sheep industry in the United States is presented, and the present status of the industry in this country and in those countries competing with us in wool production is shown. The most striking fact in connection with the sheep industry in the United States is that the pro duction of wool has not increased for forty years. This is due to several reasons. Sheep may be grown under two main systems, on the range, or in connection with general farming. Because of the great amount of free lands in our Western States during the last century vast flocks of sheep roamed this western territory. But this land was gradually taken up by settlers until at present sheep growing under the range system is becoming impossible. The extent of sheep growing that will be carried on as a part of general farming operations depends upon the relative advantage the farmer may gain from growing sheep or turning his energies in other directions. In addition, when he raises sheep, the farmer finds it to his advantage to have those breeds which are good mutton sheep rather than the pure Merino, the best wool-bearing breed. The reader interested in wool-growing as an agricultural problem will find this first part of the study most suggestive, and the non-agriculturalist will be able to understand the "farm bloc" better after having read Mr. Smith's survey of this one phase of the agricultural situation.

In the second part of the study our wool tariff history is presented. In all the tariff acts passed in the United States since 1816, with the exceptions of the Acts of 1894 and 1913, wool has been given substantial protection, with the rates under the Fur dney-Mc Cumber Act of 1922 higher than under any previous act, with the exception of the Emergency Act of 1921. The history of the tariff on wool under the earlier acts is necessarily briefly given, but the rates since 1913 are adequately discussed. One cannot expect tariff rates, classifications, and the discussions of the merits of ad valorem v. specific rates to be highly entertaining, but Mr. Smith has developed the mechanics of the problem very satisfactorily.

The third part of the study should prove the most interesting to the student of economic problems. Here Mr. Smith enters on the highly controversial undertaking of an evaluation of the tariff on wool from the standpoint of public welfare. In the first place, it is shown that the duties levied upon wool have been empirical and experimental in character, and that there is no scientific method of determining the proper rate of duty. The most widely advocated rate is one that will equalize the cost of production at home and abroad. The difficulties of securing accurate cost data are pointed out. Mutton and wool are produced jointly. What part of the costs should be allocated to wool? Assuming the costs can be properly allocated, should the costs of the more or less efficient home producers be considered? If the costs of home producers can be determined, how can American authorities find out the costs of foreign producers? As a matter of fact, no scientific determination of the rates is made, unless political log-rolling may be considered a science.

Who bears the burden of this unscientifically determined tariff on wool? Mr. Smith shows conclusively that it is borne by the consumer in one of three ways, by paying higher prices for woolen goods, by the necessity of using goods of poorer quality, or by going without these goods. The burden borne by the consumer, moreover, is not simply the amount of the duty. In the course of the manufacture and sale of the goods the higher price of wool caused by the duty is pyramided to an amount much greater than the total of both the enhanced receipts of the wool growers and the revenues obtained by the government from the duty. Illustrative of this is the fact that in 1923 the government collected around 46 millions from the duty on imported wool. Mr. Smith assumes that the domestic wool producers were benefited by the full amount of the tariff rate, causing their receipts to be 33 millions more than if there had been no duty. But because of the pyramiding of the increased costs to the wool merchant, the manufacturers and middlemen, it is calculated the cost of the duty to the consumers was about 175 millions.

But is not this burden to be borne cheerfully by the consumers so that the resources of the country may be fully developed and that the United States may be a self-sufficient country? Since under the high duties of the Fordney-McCumber Act we produce less than half of our wool supply, one wonders what price selfsufficiency? Furthermore, because of the peculiar nature of the sheep industry, the fact that it is changing from the range to the farm and that the mutton side of the industry is becoming more important, Mr. Smith reaches the conclusion that while free wool might temporarily reduce our wool output about 15 per cent, yet in the long run there would be no appreciable reduction.

After his careful analysis of the sheep industry, his presentation of the effects of the wool schedules in our various tariff acts, and his painstaking researches as to the advisability of protection for wool, Mr. Smith thinks the tariff on wool injurious to public welfare, a conclusion which shows at least a fair degree of soundness in the opinions of the "impractical" academic economists who by the use of economic theory have reached similar opinions concerning protection.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsMERE FOOTBALL

November 1926 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Lettter from the Editor

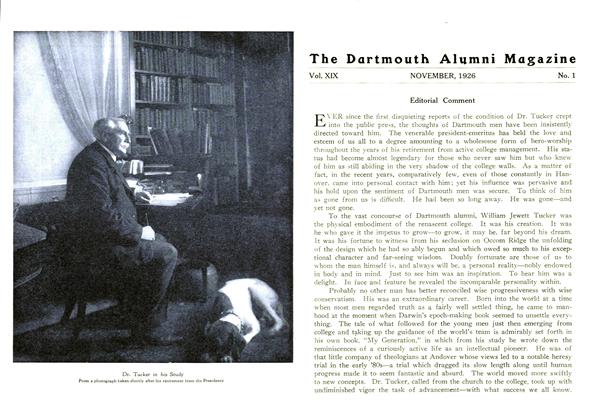

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

November 1926 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1926 By Prof. Nathaniel G. -

Article

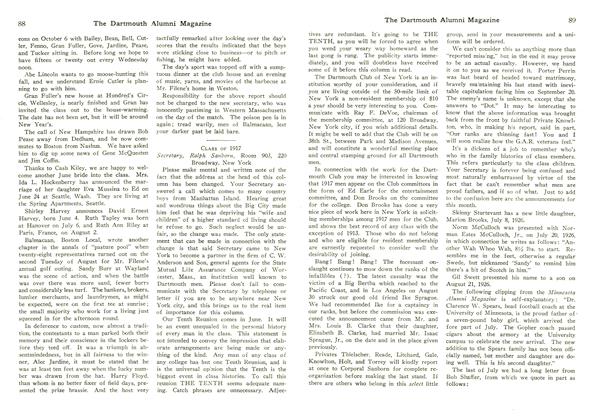

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1930

November 1926 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1926 By Ralph Sanborn

Earl R. Sikes

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MAY 1969 -

Books

BooksMalthus Repackaged

MAY 1978 By ARTHUR KANTROWITZ -

Books

Books"Psychology and the Days Work"

February 1919 By CHARLES FREDERICK ECHTERBECKER -

Books

BooksWINDOW IN THE SEA.

December 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksNEO-CONFUCIANISM, ETC.: ESSAYS BY WING-TSIT CHAN.

MARCH 1970 By SHU-HSIEN LIU -

Books

BooksCharles Darwin Adams: Demosthenes and His Influence

AUGUST, 1927 By William Stuart Messer, Edwin J. Bartlett