(From the Lowell (Mass.) Courier-Citizen)

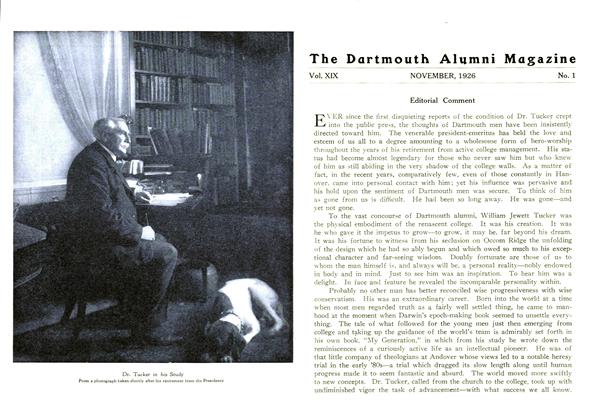

Within a month of the passing of Dr. Eliot comes the news of the death of his great contemporary, Dr. William Jewett Tucker, president-emeritus of Dartmouth, at the ripe age of 87. The parallel records of these two notable servants of the cause of American collegiate education might well tempt a modern Plutarch. Each wrought nobly in his chosen field—and each in his different way.

It would not be an overstatement to say that by the Dartmouth men of two generations Dr. Tucker was virtually worshipped. There was about the man a nobility, alike in thought and in appearance, which inspired others as it is given to few men to inspire those about them. Coming to Dartmouth College in 1893 when its fortunes were at nearly their lowest ebb, Dr. Tucker breathed into it the breath of a new vigor and set it on the road to something far transcending even his own dreams of its future. He lived to see the "little college," which Wheelock had founded in the wilderness and which Webster had saved from extinction by his eloquence and a timely tear, grow to its present magnitude and current fame. One has no hesitation in ascribing to Dr. Tucker the credit. He founded the New Dartmouth as surely as Dr. Wheelock founded the old.

Yet his actual presidency covered a surprisingly brief period of years. He took command at Hanover in 1893 and he retired from the presidency in 1909. But in those 16 years he stamped upon the institution the indelible impress of his personality and left behind him a tradition which Dartmouth men have made a creed. The natural hesitancy which supervened when the compelling impulse of his active management was withdrawn was fortunately brief, and has been followed by the amazing growth fostered by the wisdom of President Hopkins who is in a sense, Dr. Tucker's spiritual child, since it was by intimate personal service under him that Dr. Hopkins learned to follow out the lines which his chief had pioneered.

There has probably been no parallel for the situation which followed Dr. Tucker's withdrawal from the presidency. Residing in Hanover still, he studiously avoided intruding himself by word or deed to the embarassment of either of his successors. With the advance of years and failing bodily health came the time when he was no longer seen, and it might almost be said that for the past decade he had, for the undergraduate body, already disappeared from earth. Yet he was living and alert, keenly interested in watching the growth of what he had planted and commenting from time to time in his books and magazine articles on the progress of human affairs.

So much for the great services which William Jewett Tucker rendered to American education—services designed to augment as broadly as possible the number of efficiently educated men equipped to serve their day; for it was not the Tucker ideal to promote existence of a few cloistered scholars, so much as to enlist greater armies properly to undertake the work of a vigorous young nation. He came to his maturity at a transitional period when old orders were changing, giving place to new, in society and in religion. He was one of the little band of pioneer Congregational liberals who in the 'Bos were tried for "heresy" at Andover—a trial which now seems utterly absurd. He was a great teacher, a great preacher—and best of all a great doer of the Word.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsMERE FOOTBALL

November 1926 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

November 1926 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1926 By Prof. Nathaniel G. -

Article

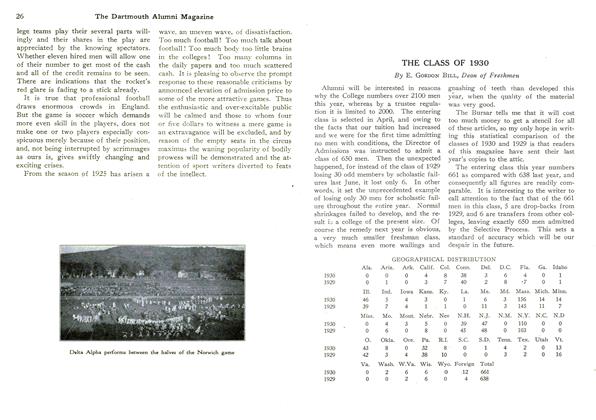

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1930

November 1926 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1926 By Ralph Sanborn

Article

-

Article

ArticleARE THE COLLEGES OF TODAY SUFFICIENTLY HONORING THE CLAIMS OF SCHOLARSHIP?

OCTOBER, 1906 -

Article

ArticleA year ago certain regulations were adopted

March, 1909 -

Article

ArticleNOTES

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

MAY • 1987 -

Article

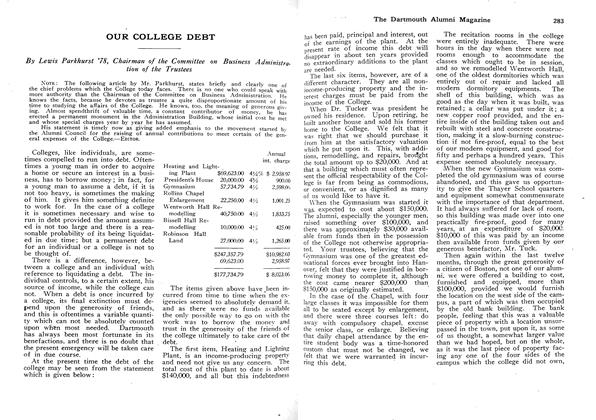

ArticleOUR COLLEGE DEBT

June, 1914 By Lewis Parkhurst '78