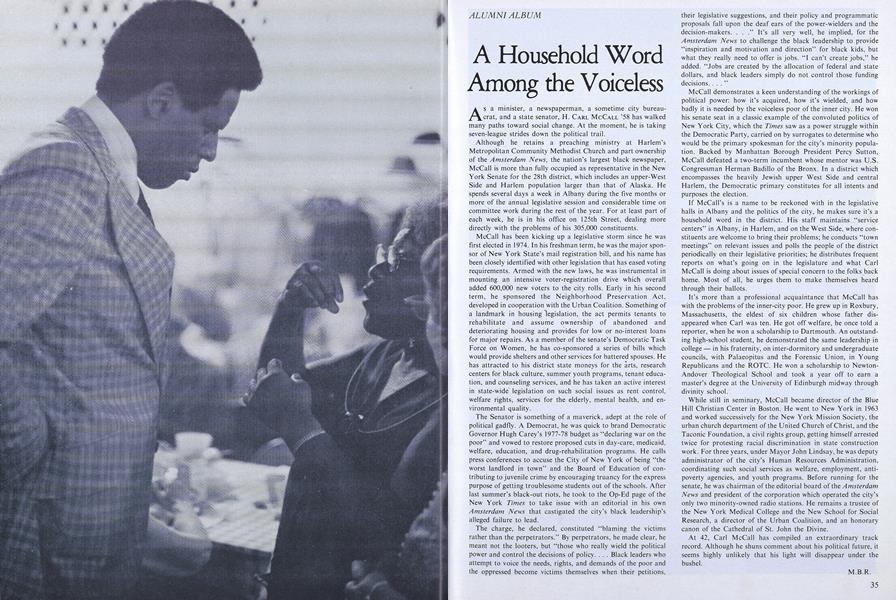

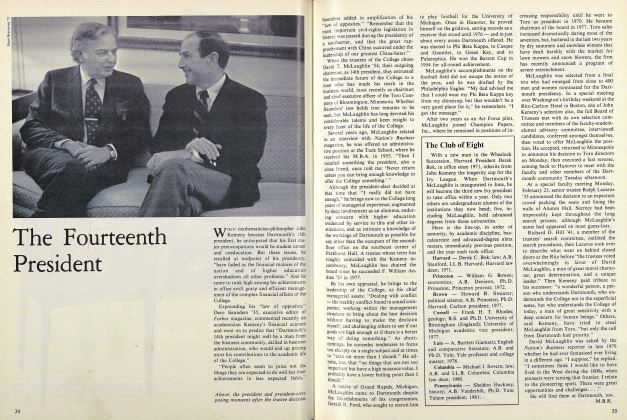

As a minister, a newspaperman, a sometime city bureaucrat, and a state senator, H. CARL McCALL '58 has walked many paths toward social change. At the moment, he is taking seven-league strides down the political trail.

Although he retains a preaching ministry at Harlem's Metropolitan Community Methodist Church and part ownership of the Amsterdam News, the nation's largest black newspaper, McCall is more than fully occupied as representative in the New York Senate for the 28th district, which includes an upper-West Side and Harlem population larger than that of Alaska. He spends several days a week in Albany during the five months or more of the annual legislative session and considerable time on committee work during the rest of the year. For at least part of each week, he is in his office on 125th Street, dealing more directly with the problems of his 305,000 constituents.

McCall has been kicking up a legislative storm since he was first elected in 1974. In his freshman term, he was the major sponsor of New York State's mail registration bill, and his name has been closely identified with other legislation that has eased voting requirements. Armed with the new laws, he was instrumental in mounting ah intensive voter-registration drive which overall added 600,000 new voters to the city rolls. Early in his second term, he sponsored the Neighborhood Preservation Act, developed in cooperation with the Urban Coalition. Something of a landmark in housing legislation, the act permits tenants to rehabilitate and assume ownership of abandoned and deteriorating housing and provides for low or no-interest loans for major repairs. As a member of the Senate's Democratic Task Force on Women, he has co-sponsored a series of bills which would provide shelters and other services for battered spouses. He has attracted to his district state moneys for the arts, research centers for black culture, summer youth programs, tenant education, and counseling services, and he has taken an active interest in state-wide legislation on such social issues as rent control, welfare rights, services for the elderly, mental health, and environmental quality.

The Senator is something of a maverick, adept at the role of political gadfly. A Democrat, he was quick to brand Democratic Governor Hugh Carey's 1977-78 budget as "declaring war on the poor" and vowed to restore proposed cuts in day-care, medicaid, welfare, education, and drug-rehabilitation programs. He calls press conferences to accuse the City of New York of being "the worst landlord in town" and the Board of Education of contributing to juvenile crime by encouraging truancy for the express purpose of getting troublesome students out of the schools. After last summer's black-out riots, he took to the Op-Ed page of the New York Times to take issue with an editorial in his own Amsterdam News that castigated the city's black leadership's alleged failure to lead.

The charge, he declared, constituted "blaming the victims rather than the perpetrators." By perpetrators, he made clear, he meant not the looters, but "those who really wield the political power and control the decisions of policy. ... Black leaders who attempt to voice the needs, rights, and demands of the poor and the oppressed become victims themselves when their petitions, their legislative suggestions, and their policy and programmatic proposals fall upon the deaf ears of the power-wielders and the decision-makers. ... It's all very well, he implied, for the Amsterdam News to challenge the black leadership to provide "inspiration and motivation and direction" for black kids, but what they really need to offer is jobs. "I can't create jobs," he added. "Jobs are created by the allocation of federal and state dollars, and black leaders simply do not control those funding decisions. ..."

McCall demonstrates a keen understanding of the workings of political power: how it's acquired, how it's wielded, and how badly it is needed by the voiceless poor of the inner city. He won his senate seat in a classic example of the convoluted politics of New York City, which the Times saw as a power struggle within the Democratic Party, carried on by surrogates to determine who would be the primary spokesman for the city's minority population. Backed by Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton, McCall defeated, a two-term incumbent whose mentor was U.S. Congressman Herman Badillo of the Bronx. In a district which encompasses the heavily Jewish upper West Side and central Harlem, the Democratic primary constitutes for all intents and purposes the election.

If McCall's is a name to be reckoned with in the legislative halls in Albany and the politics of the city, he makes sure it's a household word in the district. His staff maintains "service centers" in Albany, in Harlem, and on the West Side, where constituents are welcome to bring their problems; he conducts "town meetings" on relevant issues and polls the people of the district periodically on their legislative priorities; he distributes frequent reports on what's going on in the legislature and what Carl McCall is doing about issues of special concern to the folks back home. Most of all, he urges them to make themselves heard through their ballots.

It's more than a professional acquaintance that McCall has with the problems of the inner-city poor. He grew up in Roxbury, Massachusetts, the eldest of six children whose father disappeared when Carl was ten. He got off welfare, he once told a reporter, when he won a scholarship to Dartmouth. An outstanding high-school student, he demonstrated the same leadership in college - in his fraternity, on inter-dormitory and undergraduate councils, with Palaeopitus and the Forensic Union, in Young Republicans and the ROTC. He won a scholarship to Newton-Andover Theological School and took a year off to earn a master's degree at the University of Edinburgh midway through divinity school.

While still in seminary, McCall became director of the Blue Hill Christian Center in Boston. He went to New York in 1963 and worked successively for the New York Mission Society, the urban church department of the United Church of Christ, and the Taconic Foundation, a civil rights group, getting himself arrested twice for protesting racial discrimination in state construction work. For three years, under Mayor John Lindsay, he was deputy administrator of the city's Human Resources Administration, coordinating such social services as welfare, employment, antipoverty agencies, and youth programs. Before running for the senate, he was chairman of the editorial board of the AmsterdamNews and president of the corporation which operated the city's only two minority-owned radio stations. He remains a trustee of the New York Medical College and the New School for Social Research, a director of the Urban Coalition, and an honorary canon of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

At 42. Carl McCall has compiled an extraordinary track record. Although he shuns comment about his political future, it seems highly unlikely that his light will disappear under the bushel.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCould it be that the political animals are hibernating?

May 1978 By Anne Bagamery -

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

May 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

FeatureCastles in the Clouds

May 1978 By George Hathorn -

Feature

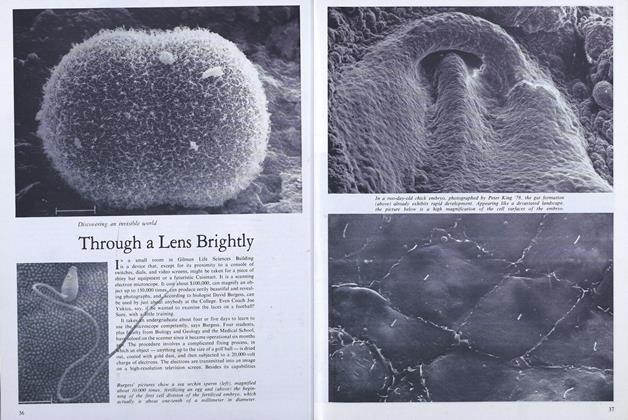

FeatureThrough a Lens Brightly

May 1978 -

Article

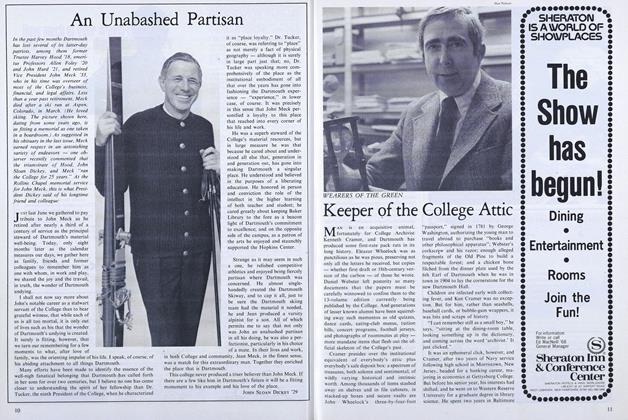

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

May 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMy Dog Likes It Here

May 1978 By COREY FORD

M.B.R.

-

Feature

FeatureManin the Red Flannel shirt

January 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureConserver of Life

April 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degrees

July 1974 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleConservator by Design

February 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleGrown by Hand

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R.