The Biblical account of the education of the boy Samuel states, "The word of the Lord was rare in those days; there was no frequent vision."

This is a description of life in an ancient time when a nomad people were violently distracted by changing conditions, when confidence was failing in government, when respect for authority was crumbling, when religious leaders were losing their prestige in the stress of daily life and the necessity of new adjustments to a transformed world of thought and action.

So it is always in periods after great social uphevals the mind of man loses its sense of proportion and as a result there develops a non-comprehension of relative values among those things which are fundamental to man's well being.

The records of American colleges in the quarter of a century following the Revolutionary War show that not even the critical attitudes of Rousseau, Voltaire and the French school had as much of a destructive influence in religious thought apparently as did the social confusion resulting from the fact of the war itself. In colleges of an enrollment of from one to two hundred there were sometimes less than a dozen men in the student body and the faculty combined who made any profession of religious conviction, and frequently a large proportion of the remainder asserted that they were atheistic.

Elderly college graduates, whom I have known, have told me, likewise, that the same phenomenon was observable after the Civil War. Precedent would have foretold that something of the sort would be existent in pronounced and distinctive form for an interval of a good many years following a gigantic disturbance in the social adjustments among the peoples of the earth, such as resulted from the World War, and is still existent.

There are one or two facts in this connection that I want to present to Dartmouth undergraduates as worthy of their attention. lam not disturbed by such a showing as is made in the recent questionnaire, for I think that the fact that approximately 75 per cent stated affirmatively that they believe in God and that nearly 90 per cent stated that they believe religion to be a necessary element of life for the individual and the community contains sufficient reassurance for even those most solicitous for the religious life of the undergraduate.

The matter which does disturb me, however, is the attitude of flippancy taken periodically by some individual or some, small group of individuals toward a matter as fundamental as religion and the obvious assumption that therein lies some mark of superior intelligence.

A true sense of religion springs from the inner consciousness of man and is transmitted by a "still, small voice." The fact that a man has become benumbed by clamor and uproar to the point where he is not sensitive to the existence of the fact of religion and cannot perceive its evidences, does little except to mark him as calloused or unobservant or unheeding.

I think that it is fair to accept it as a truism that the burden of proof rests upon men who argue for the dispensing with the institutions of society or the beliefs of man which, through long ages, have proved helpful and comforting to humanity. Progress demands that a certain proportion of these be discarded from time to time but a spirit of truth demands that they shall not be abandoned until some valid evidence is marshalled against them.

Personally, I am not so concerned about the occasional undergraduate who professes unbelief as I am by the fact that only very occasionally does one such base his unbelief on anything except the most abysmal ignorance in regard to the origins of religion and the evolution of religious theory. Such an attitude is not worthy of a college man.

Unbelief is not a negative attitude and he who argues for trial of the unknown as against the known is arguing for anarchy in place of law.

I am willing to grant the right of unbelief to a man who has considered and informed himself in regard to the origins of religious thought through a study, for instance, of the significance of the Greek gods, the Mosaic Law, the philosophy of Buddha, the precepts of Confucius, and the idealism of Jesus. lam not willing to believe that undergraduate to be intelligent whose unbelief is based solely on opinion derived from discussion in stove leagues or in midnight sessions in dormitory or fraternity house. lam not willing to grant to that man the right of unbelief. He has not accepted the obligations which go with the needful assuming of the burden of proof.

We hold that man ridiculous who discusses history without ever having subjected himself to the discipline of historical study. The world is full of men recognized as cranks, who undertake to develop scientific truth without any knowledge of the scientific method. We smile at the criticisms of art and literature by men who frankly have shut their minds against appreciation of the one or the other. No more should we take the opinion of the man seriously in regard to religion who seeks neither knowledge of nor contact with religious things.

By the same token, little heed should be given to the arguments of men who declaim against religion because of the obvious defects of many a human agency which has been devised or espoused by groups here or there. Human fallibility enters into the interpretations given to religion as it enters into the interpretations of all forms of human thought. When this is the case, however, the indictment should be against the fallible agent and not against the cause it purports to represent.

There is not time in a talk of this sort to state arguments and to reach conclusions. I can only make assertions, asking you to give such consideration to these as you may feel them to deserve.

In all forms of life it is true that powers unused tend to become lost. The Indian fakir who holds his hand aloft for years, unused, suffers atrophy of the hand. The athlete, who drops his athletics, becomes soft and incompetent in athletics. The recluse, who, in dislike of the conventions of society, withdraws from social contacts, loses his capacity at length to be at ease where these are required. Charles Darwin tells how, from an appreciation and sensitiveness to poetry and music in his youth, he reached the point, after years of specializing on biological investigation, where music and poetry became distasteful to him.

On the other hand, there is the possibility, indicated by William James in one of his essays, wherein he says that man has the capacity to develop new resources in his mind by exercise of his mental faculties in the same way that he can build up undeveloped portions of his body by special exercise of the muscles affecting these. Ignatius Loyola prescribed particular and rigorous methods of prayer for his disciples, frankly stating that these were designed for "spiritual exercises."

Is it intelligent for a college man, who knows nothing of the history of religious thought, who knows nothing of what the spirit of religion has done for the advance of humanity, who has no acquaintanceship with the great literatures and the great philosophies of religion, and who avoids rather than seeks the best contemporary thought in regard to religious affairs, to take an attitude of unbelief ?

We take pride in the reputation of this college for liberalism, for courage and for intellectual competence. We recognize validity in the method of the class room in the college which challenges blind belief and which says, in effect, that an honest doubt is more respectable than an unsubstantiated opinion. If we are sincere in these things and if we understand the meaning of what we say, we must, by the same token, deny the right to an un-informed individual of that positive state of mind which he calls unbelief in religious things. It is not a liberal attitude to close the mind against any aspect of truth; it is not courageous to take a stand which requires no courage; it is not significant of intellectual competence to hold an opinion simply because of ignorance of evidence to the contrary of that opinion.

As in the days of Samuel, so now the word of the Lord is rare and there is no frequent vision. Shall we, as seekers after truth, conclude, therefore, that there are no such things as God's laws and that these have never been demonstrated?

There are men in the world who do not seek the easiest way of life; there are men to whom difficulties are a challenge; there are men to whom hardship and rigorous discipline are preferable to soft living. In looking over the College and the possibilities for influential leadership therein, I sometimes query in anxious speculation whether there may not be some to whom the very rarity of the word of the Lord in these days and the infrequency of vision may not be an invitation. It would be an indictment of the College if there were not.

Edwin Arlington Robinson, the poet, speaking of this matter, once said that to him the world was not a prison house but rather a spiritual kindergarten in which millions of bewildered infants tried to spell "God" with the wrong blocks. The question which I wish to leave with you today is whether a man is justified in assuming that the word "God" does not exist because he does not know how to spell and is not willing to make any effort to learn.

A Chapel Talk May 26, 1927

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S 158TH COMMENCEMENT

August 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICIAL FITNESS V.

August 1927 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D., -

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1927 By J. R. Chandler '98, Clarence G. McDavitt '00 -

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES HOLD MEETING IN HANOVER

August 1927 By Hanover, N. H.,, E. K. Hall -

Sports

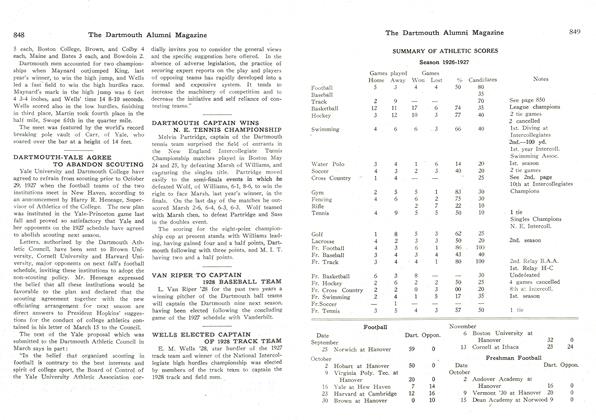

SportsSUMMARY OF ATHLETIC SCORES

August 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

August 1927 By Herrick Brown

President Hopkins

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate and His College

November 1928 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleAN ACADEMIC HUNDRED THOUSAND

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleFACTUAL KNOWLEDGE IMPORTANT

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleWIDENED BOUNDARIES

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleLIVING AS AN ART

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleEMPHASIS ON CONSTRUCTIVE THOUGHT

November, 1930 By President Hopkins

Article

-

Article

ArticleSenior Fellows Named

May 1956 -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

OCTOBER 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticlePhysical Oversight of the Undergraduate

AUGUST 1930 By Dr. John W. Bowler -

Article

ArticleNEWS AND NOTES

MAY | JUNE By Marley Marius ’17 -

Article

ArticleA Kind of Knowing

September 1980 By Patricia Berry '81 -

Article

ArticleCaveat Emptor

OCTOBER 1982 By S.G