THE one hundred and sixtieth year of the College begins. At this time, in accordance with custom, greetings are extended to the undergraduate body in behalf of the Dartmouth fellowship—a fellowship world-wide in its extent and in its age older than the nation itself. For a brief time, amid the many distractions of these opening days, we turn our thought to a few of the many matters which deserve attention in connection with the obligations which beconie ours in claiming the privilege of membership within this college.

It has been told from times long ago that the people of Leyden, as a reward for their heroic defense under William of Orange, were offered either exemption from taxes or a university. They chose the university. In more recent times the people of the United States have made like choice. Not only that, but each succeeding generation has shown itself willing to enlarge its effort and to assume new and greater financial obligations to support and increase the effectiveness of its educational processes.

PRESENT GROWTH OF COLLEGE

The expenditures of state colleges and universities in this country, provided for mainly by taxation, are running close to the stupendous total of two hundred million dollars a year. Meanwhile, the carefully comoiled figures of private benefactions to colleges and universities, largely to those of private endowment, show that in the year 1927 one hundred and twenty-nine million dollars were given to enhance the educational advantages which these institutions represented.

The scope of the American educational experiment, the cheerful acceptance by the American people of the orinciple of taxation for educational expansion, the unceasing generosity of individual donors for the enrichment of opportunity in colleges of private endowment, and the self-sacrificing ambition of the American parents that their sons and daughters may have access to the privileges of higher education,-all these are sources of wonder and admiration to the peoples and governments of other countries. From them in a steady stream come groups and individuals as representatives to make study and to report upon the effect of such an effort to disseminate learning throughout the territories and among the citizens of a great republic.

It is meet that those of us who are most definitely beneficiaries of such changed conditions should know the facts and it would seem desirable that consideration be given to the matter of obligations imposed upon us individually and collectively by them.

The financial income of higher institutions of learning in the United States in 1912, excluding endowment, was ninety million dollars. In 1922 this had tripled and exceeded two hundred and seventy million. The decade ending in 1932, when the class now entering college graduates, will probably show that the rate of increase has not diminished.

Andrew D. White said in public address in 1874, speaking of American colleges, that a visitor to most college towns would find the railway station and the county jail better built, heated and equipped than the halls of learning. Moreover, he said that in American colleges in general would be found no adequate faculties, no libraries offering any idea of the existing condition of knowledge, no illustrative collections or laboratories, and next to no modern apparatus or instruments.

I will not pause to speak of how different are the circumstances in which the college student and the college teacher of the present day are placed. I will simply add, to make my point local and specific, that in the last academic year the gifts received by and promised to Dartmouth College exceeded by a million dollars the total assets of the college of two decades ago. Never theless, the college of that time and of earlier years was in the character of its undergraduate body, in the self- sacrificing devotion of its instruction corps, in the consecration of its administrative officers and in the faith of its alumni, winning the regard, breeding the confidence, and establishing the respect that accounts in considerable measure for the comparative well-being of the college of today.

EFFECT UPON THE FUTURE COLLEGE

The question inevitably arises, as we consider these enlarged resources, "Have we within ourselves the qualities as undergraduates, college officers, and alumni, which will make this college, decades hence, commen- surately greater in achievement and in influence for the public weal?"

The college of the present was previsioned and made possible by the anxious solicitude and the purposeful effort of men of times past. We of today are in large degree formulating the Dartmouth of the future.

I am making no plea for a restoration of the methods or of the forms of the past. These have rendered their acceptable service and in many cases they have completed their usefulness. Nevertheless, in discarding these or supplanting them it is well for us to be sure that we do not discard the spirit which animated them and must dominate the affairs of the College if it is to perpetuate its own individuality which in part has made it strong and given significance to its public service.

New times, however, demand new conditions and the technique of educational method must keep pace with the changing status of the transforming world in which we live if the process we call education is to be actually educational.

The undergraduate of today stands upon the thresh- old of a world, contemplation of whose problems would have staggered the imagination of generations past. The power development of the country has created a force equivalent to the work of 150 slaves for every man, woman and child in the United States. All affairs of life have become larger in dimension and move at a greatly accelerated pace. This is a situation which demands realignment of all our physical, intellectual and spiritual forces, if mankind is to adjust itself to its new environment. Here are new conditions for education to meet.

DUTIES OF THE PRESENT GENERATION

As beneficiaries of special privileges and rich opportunities which have come to us from men who assumed great obligations to the times in which they lived, the responsibility falls upon us to understand our own times and to qualify ourselves to contribute to the solution of its problems. To the extent that life is more involved, we are under moral obligation to develop so much further our capacity for understanding. To the extent that its problems are more complex, we are responsible for developing more accurately our mental acumen for intelligent solution of these.

Let us for a moment consider how high intelligence, open-mindedness and courage operate in industrial life in meeting modern conditions. There was, a few decades ago, no major problem of engineering and no excessive financial expense demanded of the village carriage shop, if community prosperity or if local taste prescribed a change from the one-horse chaise to the covered phaeton. When recently, on the other hand, the purchasing power of the American public and popular conception of what constituted desirable style in motor cars led Mr. Ford to abandon his Model T, it required years of planning by a skilled engineering corps and the expenditure of more than a hundred million dollars for the retooling alone of his plants before he could begin to make the machines to manufacture the parts from which the promised car should be constructed.

Compare the painstaking research, the accumulation of data from experience and science, and the susceptibility to logical conclusions in this or other illustrations which are available in the field of big business, compare these with the attitude of the public at large towards adapting its forms of government, its tenets of religion, or its codes of social relations to modern life and there will be somewhat evident the task that devolves upon education in our time if it really is to affect the conditions under which men live.

In this connection we may well consider the statement of Freeman in his historical essay on "The Growth of Commonwealths," wherein he comments on some of the slogans of the day as follows: " 'Stand fast in the old paths'; 'Respect the wisdom of your forefathers'; are the sayings which the dull conservative throws in the teeth of reformers. These are very good sayings; but it is to the reformer and not to the conservative that they belong. The reformer obeys them; the conservative tramples them under foot. The wisdom of our fore- fathers consisted in always making such changes as were needed at any particular time; we may freely add, in never making greater changes than were needed at any particular time."

It is upon those who are the youth of today that civilization depends for its status tomorrow. It is mainly with youth that institutionalized education has to do. Therefore, the aspiration of the College naturally arises that through membership in it and utilization of it, individuals and groups shall be developed with knowledge of social backgrounds and with sense of social responsibilities which shall make them capable of bettering the conditions of mankind as well as qualified within themselves for more largely deriving the satisfactions from life it so prodigally offers to those mentally and spiritually receptive to these. This it should be recognized is serious business and is not to be undertaken lightly or continued superficially, if real advantage is to be expected from it.

THE REVOLT OF YOUTH

Let us for a moment examine the conditions under which the College undertakes its share of these responsibilities.

In the beginning I am going to argue that the youth of today could, to the advantage of its own generation, be somewhat less assured in regard to its own immediate sufficiency for creating a new structure of life; that it could, to its own ultimate welfare, be less certain of the finality of its own opinions; that it could, to its own eventual self-respect, be less cavalier in its judgments of men and deeds of the present and the past; and that it could, to the end of safeguarding its own span of life against ill, be patient to serve a longer apprenticeship before arrogating to itself an assumption of complete wisdom in all matters affecting its own world.

I do not make these statements in any spirit of petulance but simply in behalf of recognition of what I believe to be fact. It is not in regard to the capabilities of youth that question is to be raised; it is in regard to its propensities. The so-called revolt of youth was a natural and in many ways a desirable reaction to the imbroglio of a generation which plunged itself into a world-war. I simply am questioning if the movement has not served its purpose and if the time has not come when an intelligently-devised, constructive attitude will be more useful to society than can be the approach to life which the spirit of the last decade has dictated within and without our colleges.

Furthermore, I am not forgetting the unquestionable fact that an impressive proportion of the great individual achievements recorded in history have been the accomplishments of men but little older than are the men today enrolled in our American colleges. This perhaps will continue to be so in the arts but elsewhere, in the physical and natural sciences, in philosophy, in social, economic, and governmental theory,—the realms of knowledge have become so vast and sense of proportion is so vital to comprehension of these that the ripened judgments of maturity are indispensable to intelligent opinion to a degree greater than ever before.

If it be true that the upward march of man in mental capacity through the ages has been coincident with a lengthening of the period of infancy in human beings, whichever be cause or effect, may it not be that still longer periods of apprenticeship would be advantageous to human progress?

No education is complete which does not breed an attitude of humility, in view of how little area in the field of knowledge any individual can possess. To return to a subject to which I have referred before, this is one reason why objection is to be raised to the vogue which has arisen in recent years among students of our American colleges of contending that nothing is to be believed that cannot be rationalized. The argument advanced is that mental processes of the individual are more important in defining truth than is the experience of the race. Thus we find some who dismiss as intellectually unworthy college loyalty, or civic pride and patriotism, or love of family or belief in God.

THE BOUNDARIES OF KNOWLEDGE

The weakness in rationalization is that it is so difficult for the wisest of men to be sure that they know what they think they know. The boundaries of knowledge are too wide and our command of the knowable is too inadequate for us ever to be certain how complete our knowledge is.

Mr. Graham Wallas, whom no critic has ever ventured to characterize as unprogressive, in hisbook "The Art of Thought" makes an interesting comment on this point. He says,

"Sometimes empiricism lags behind science, and sometimes science lags behind empiricism. Seventy years ago, for instance, Baron Justus von Liebig was the acknowledged leader of the chemical science which then claimed to cover the field of the empirical processes of selecting and cooking food; while the chef of the Reform Club might be taken as being a leader of the empirical 'mystery' of food-preparation, handed on by one chef to another and indicated in the 'cookery books' which were so strikingly unlike the text-books of chemistry. We now know that if in 1855 the Reform Club chef had been asked to prepare the best dinner he could, and if Baron Liebig had been asked to order another dinner, to be prepared in the same kitchen and by the same body of cooks, the chef's dinner would have been much the better, from the point of view of health as well as of enjoyment."

This often, if not usually, happens in a conflict between the unsubstantiated assumptions of partial knowledge and the codified practices based on long experience.

Among the many changed conditions of modern times is the extent to which science has made long life in good health possible to men in contrast to former centuries when an expectation of life beyond fifty years could be assumed for but a small percentage of the population. A vastly increased store of human experience and a far richer harvest of the fruits of ripened judgment have herein been made available to human beings for meeting the more numerous and more complicated problems of our age.

It would be grave loss to the world if it were denied the enthusiasms and idealizations of youth. It would, on the other hand, be unjustifiably hazardous to the values of a civilization, of which we are for the time being trustees, if we were to eliminate all empirical methods before we have acquired any substitutes devised from sufficient data to be even near scientific. In inexperience, data may seem to have been exhaustively assembled when, as a matter of fact, use has been made of but an imperceptible proportion of the available supply.

An attitude or an action out of character is always open to the suspicion of being insincere. It is not a normal attitude of youth to be cynical, pessimistic, or misanthropic. For youth to assume these is an affectation. The spirit of education is first of all a spirit of genuineness and if the spirit of sincerity disappears or even fades among considerable groups in our formal institutions of higher learning, the institutions them- selves will inevitably lose strength and character. They, in turn, will become as futile as the spirit of melancholy confusion which some undergraduate groups are so prone to espouse.

All of this is not to be taken as undervaluing qualities without which the college would lose vitality,—such qualities as the spirit of inquiry, the open-mindedness which seeks intelligent convictions, the healthy agnosticism of a man unconvinced, or the unwillingness to accept dogmatic assertion unsubstantiated in experience and untenable in theory.

THE INTELLECTUAL POSEUR

The assertions are, however, to be taken as antagonistic to the last degree to the attitudinizing and posing which makes an individual or a group impervious to the influence of real education. One can cultivate cynicism, skepticism, or unbelief far easier than one can gain understanding, appreciation, or conviction. Hence, poseurs of the former type so frequently appear in college life.

The whole of Alexander Pope's assertion deserves as much attention as that widely given to its first part: "A little learning is a dangerous thing; Drink deep or taste not the Pierian spring. There, shallow drafts intoxicate the brain But drinking largely sobers one again."

I have allowed myself these animadversions not because I believe them to apply largely to the college youth of today but because they apply in some degree. Furthermore, at the most disadvantageous point, they apply in major degree to the columns of the press of the American college. There, in comparison with one understanding utterance based on intelligent interest as to how education might be made more helpful to humanity or more profitable to the individual, we find hundreds of cleverly written editorials and articles subversive of all conventions, of all standards, and of all ideals, if these interfere with individual desire, individual caprice or individual self-indulgence. There, in place of any frequent discussion of what undergraduates might do to help their respective colleges we find the tiresome reiteration of what the colleges ought further to do for the undergraduate.

Fortunately, these utterances do not represent the mind of the undergraduate bodies. But their existence and reiteration subtracts a measurable element of strength from accomplishment of the college purpose that, placed in support of helpful conventions, desirable standards, and idealistic aspirations, would add greatly to the college worth.

My concern is not so much with the present as with the future, if conditions widely prevalent in college publications continue. It is a part of the psychology of human beings that the printed word carries influence all out of proportion, many times, to the importance of the individual opinion from which it is derived. M. Briand stated an unquestionable fact when, addressing the newspaper men in Geneva at the opening of the last League Assembly, he said, "Humanity does not always obey reasoning, but is often penetrated by the force of a word. We must believe in the mystic force of words."

THE PUBLIC MIND AND THE COLLEGE

For a further moment, against what background of public mind is the thinking of the College to be set in these months before us?

Each new college year represents enough of a turn of the kaleidoscope of time so that it has a distinctive coloration of its own. The political campaign in progress now ought to tumour attention with greater definiteness than ever before to a consideration of how the welfare of a community, though a great one, can best be conserved, and to a consideration of what are the respective rights of the individual and of the group in the rapidly increasing congestion of population in a world of decreasing size.

In some respects there are grounds for positive optimism in regard to the workings of our political democracy. The demands of the time have produced their needed men, and despite the wishes of the more self-centered interests of the major parties, leadership has been entrusted to two citizens of high integrity, each of whom has been tried and found admirable in public service. These alike have the powers of keen intelligence and are independent in thought; and these alike are unselfishly eager to enhance the material prosperity and moral integrity of the people of the United States.

When we turn, however, from the results of processes by which leadership has been selected to the plane of popular discussion of the issues of the campaign, it is difficult to express the same satisfaction.

We have one of the greatest opportunities since the arguments which followed the Constitutional Convention in 1787 for a discussion of fundamental theories which have to do with the obligations and limitations of constitutional government. We in our national life at the present time have situations of vital significance that call for reflection upon the whole philosophy of the desirable boundaries and the necessary restrictions of authority of the State.

At this point let it be said that herein the press of the country is entitled to appreciation and respect in marked degree as an educational influence. It senses and responds to these conditions far more understandingly than does the so-called "popular mind."

The latter, oblivious to the overwhelming importance of the issues involved, and disregarding the unimpeachable characters of the candidates proposed, deals in tittle-tattle and personalities regardless, alike, of fact and of any possibility of its assertions being true.

One candidate is accused of having seen so much of the world as to have lost his interest in his own country; the other is charged with having lived so provincially as not to know problems of his own land. One is pictured literally as desirous of setting up a bar in every home; while the other is as literally charged with desire and intention, if elected, to invade every home in search of contraband. Temperaments, personal habits, domestic relationships, racial antecedents, religious affiliations, and even physical appearance are discussed for hours, usually falsely and always cheaply, unworthy even of the limited intelligence of those participating in the discussions. Under such circumstances, it is difficult not to fall subject to the spell of Disraeli's words, "That fatal drollery called representative government." There will be some criterion of the value of the educational process for developing an intelligent and responsible citizenry when it becomes evident what is the response of our undergraduate bodies to the great opportunities of the political situation today. This is entitled to discussion on the intellectual plane of papers in "The Federalist" in 1788. Up to the present time, the popular discussion has hardly conformed to the standards of the "Police Gazette" in its heyday in the Gay Nineties.

Certainly, if within our college and university constituencies we cannot assume a more solicitous interest and a more responsible consideraton of these matters than is existent in the country at large, individuals and the public are entitled to inquire, as some already have inquired, "Wherein is the influence upon or gain to society of higher education?"

THE COLLEGE OPPORTUNITY

Finally, I would revert to the matters to which I referred at the opening of this address, and call attention to the wealth of resources which the college today places at the disposal of the man who wishes to utilize them. No such opportunity for deriving intellectual advantage easily has ever been offered to the youth of any nation or of any time as in the American college of today. What is true of the American college at large, I believe to be particularly true of this, our own college.

Books, the record of the wisdom of the ages; a faculty made up of carefully trained scholars, eager to guide ambitious minds; specially designed laboratories and scientific apparatus available to the use of those who seek their benefits; an undergraduate body in which discriminating choice of friends may make for intellectual inspiration and cultural refinement, as well as for social enjoyment,—all these, and many another value, attach to and are available at Dartmouth in these days of your undergraduate membership.

What will be your response, in the matter of preparing yourselves for lives of appreciation and lives of service, compared with the response of men of former times who so greatly valued the meagre resources of the college of their day and who so greatly profited by these?

I hesitate a little, before such stern critics of emotion- alism as are to be found among the undergraduate body, to bespeak the memories of men of the time of my own undergraduate life in this college, but these are memories of affection for its associations and its life as well as appreciation and respect for the advantages it offered. It is an experience that ever has been common to Dartmouth men. May the period of your stay here enrich your lives as it has enriched the lives of thousands who have sought the association before you. Of your days here, it may be said, as in another connection Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote:

"The days are ever divine. They are of the least pretension and of the greatest capacity of anything that exists. They come and go like muffled and veiled figures, sent from a distant friendly party; but they say nothing, and if we do not use the gifts they bring, they carry them as silently away."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThis New Library

November 1928 By Henry B. Thayer, '79 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1914

November 1928 By John R. Burleigh -

Article

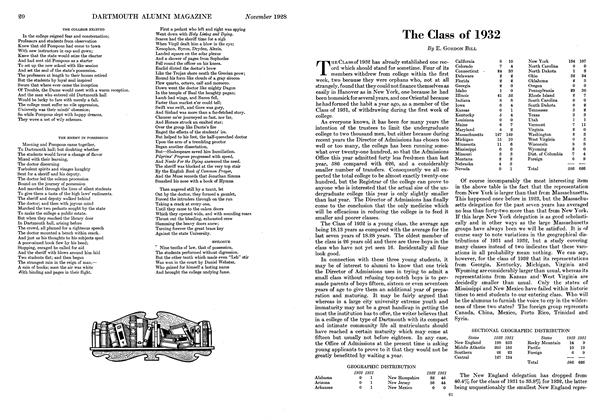

ArticleThe Class of 1932

November 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

November 1928 By Charles D. Webster, Air Reduction -

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

November 1928 By Edwin D. Harvey

President Hopkins

-

Article

ArticleThe Opening Address of Dartmouth's 162nd Year

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTRUE PORTRAITS RARE

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleFACTUAL KNOWLEDGE IMPORTANT

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleLIVING AS AN ART

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleEMPHASIS ON CONSTRUCTIVE THOUGHT

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleVALEDICTION

April 1934 By President Hopkins

Article

-

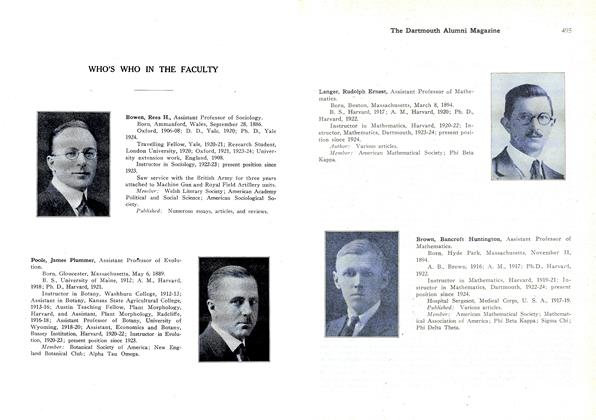

Article

ArticleWHO'S WHO IN THE FACULTY

April, 1925 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

MAY 1969 -

Article

ArticleN. E. College Conference

DECEMBER 1970 -

Article

ArticleMed School Awarded $5.4 Million Grant

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH OUT OF DOORS IN THE EIGHTIES DARTMOUTH OUT OF DOORS IN THE EIGHTIES

January 1924 By Charles Sumner Cook '79 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH TIES YALE

December 1979 By SENSATIONAL SURGE