It is to be recognized, of course, that the crises of peace do not formulate themselves so dramatically as do those of war and that consequently they cannot evoke the same emotional response. Neither in peace can the eventual calamities of unmet challenges in social adjustments commandingly call for the self-abandon that is imposed by catastrophe immediately impending in war. At the same time, if, in our academic one hundred thousand which will enter American colleges this year, or in any subsequent hundred thousand of any specific year, we could assume in very minor degree a concern for public welfare, an acquiescence to undergoing the rigid discipline essential for adequate preparation for life, and a willingness for some mild foregoing of selfinterest—if we could assume these, existent hazards to civilization could be removed which, if allowed to endure too long, must become operative as factors dangerously disintegrating to the world's social fabric. The developments of science are making amenable to human will gigantic forces hitherto concealed in nature's storehouses and these can be released and directed by infinitesimally small minorities with destructive effectiveness against vast majorities. Meanwhile, all controls in the world have become so weakened that the deterrent effect of these no longer affords the protection which heretofore has always been existent.

No man can know all things. No man can even foretell what things it will in the immediate future be most important to know. Consequently, the desirable results are that he shall acquire facility in learning easily, that he shall acquire the will to learn accurately, and that he shall acquire the taste for learning continuingly. Recently, when occasion has arisen for discussing educational theory, I have been calling particular attention to what should be the central aim of the liberal arts college, such as Dartmouth is, to develop a habit of mind rather than to impart a given content of knowledge. This is, of course, but a variant of the statement, which the liberal colleges have reiterated often in one form or another, that their concern is far greater with how men shall think than with what they shall think. It is even more a responsibility of higher education in the liberal college to elevate the mind of man than to enlarge or sharpen it. Of what purport to be facts, comprised in the knowledge that a man acquires in the course of securing a formal education, some will eventually develop not to be facts, others will prove to be inapplicable to the problems of his personal life, and most will be forgotten.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

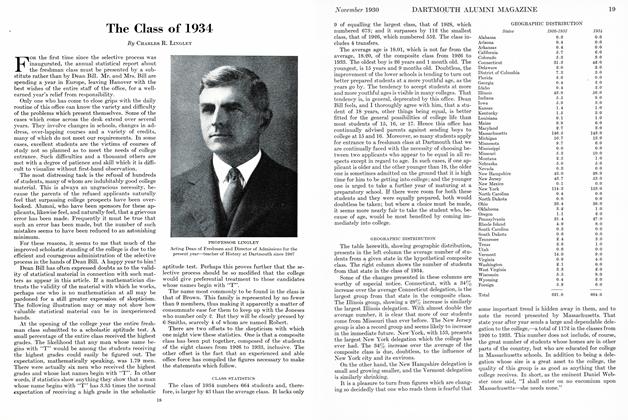

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

November 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1913

November 1930 By Warde Wilkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1920

November 1930 By Allan M. Cate -

Article

ArticleA Course in the Department of Biography

November 1930 By Harold E. B. Speight

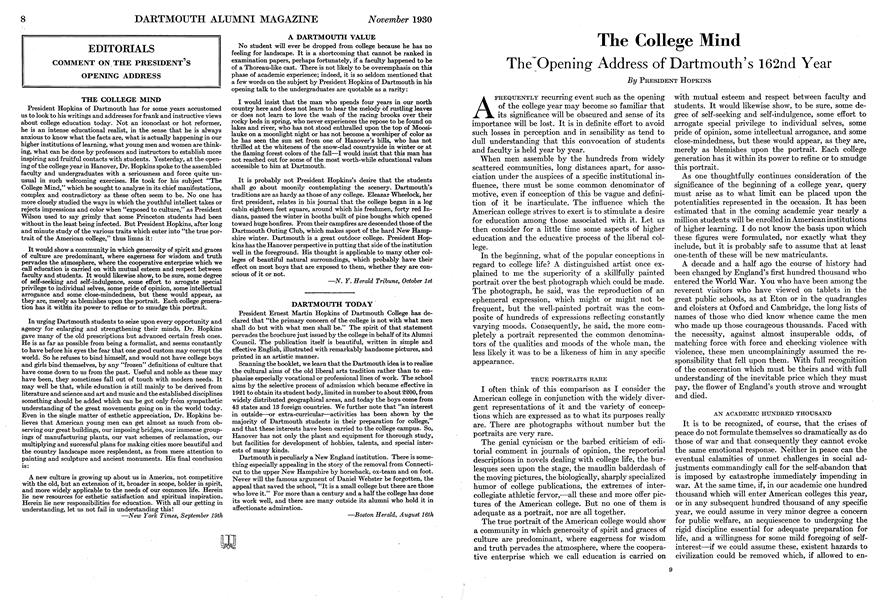

President Hopkins

-

Article

ArticleBELIEF

AUGUST, 1927 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate and His College

November 1928 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTRUE PORTRAITS RARE

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleMIND VERSUS BRAIN

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleWHAT CONSTITUTES CULTURE

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleEMPHASIS ON CONSTRUCTIVE THOUGHT

November, 1930 By President Hopkins