By RichmondLattimore '26. Ann Arbor, Mich.: TheUniversity of Michigan Press, 1966. 83pp. $4.00.

About ten years ago The Times LiterarySupplement of London gave its first two pages to a feature article assessing a large group of translations from the Greek. Noticing Richmond Lattimore's name among several at the head of the article, I began to read it, but with a growing apprehension. I wondered how the American in whom I was chiefly interested would fare when England's best scholars were all being scolded for their shortcomings. Lattimore was saved for last; he fared very well indeed. He was presented as the standard by whom others must thenceforth be judged.

This seemed surprising only because justice is too seldom so magnanimously done, particularly when the contest is international. If there was any doubt among his own countrymen before the appearance of the TLS appraisal, the opinion is now general that his translations are the most skillful of his generation, bringing over from the Greek accurate equivalents of meaning in forms suggestive of the original that never fail to be good English poetry.

It may have been this authoritative recognition of Lattimore the translator that encouraged his publishers to issue in quick succession some volumes of his own poetry, of which this is the third. (A fourth came out recently in England.) His friends have known a few of the poems for a long time, from their appearances in The Hudson Review,Poetry, and other scrupulous journals. Still, it is odd that a fine original poet should have lived so long in the shadow of the translator.

One reason, I think, is that his is usually a subtle and demanding poetry of the sort that may take a decade or so to establish its authority. Many of the poems call for the kind of attention that English teachers ex- pect their students to give to "Gerontion" or Mauberley." It seems to me that some of Lattimore's poems are just as worthy of such attention as these are. Sometimes the early phrases promise little through half a poem s length, until the sensitive reader realizes that each has been preliminary to a later one that develops its relevance. As the poem, toward its conclusion, expands under his eyes, it demands a return to its beginning. Then the wrought, scrupulous perfection emerges, justifying the stark onset. "Begin Autumn Here" is a brief example:

Unbuild the form of heat upon tne scattered and displayed shapes of slate water. Here the half-sunken stone aniens its mirror to cold silence; pines wait wind's collapse to shield them in no sound; stars cool in night water. Here build, too, illusion. This stone-and-root- cross-writhen ground grows bone and nerve, decays. The bold hemisphere faces harsh dynasty. Angry suns glare and wheel back, and night blanks. Even we clutter the springs of our outriding air with our bad wisdom and brainfull of de- bris.

Our world will wreck on despair yet. Still water will slate, stone shine, star drown. Illusion is as real as real. Imagination is what we are.

As he does here in the fifth line from the last, Lattimore tends to drop an epitomizing phrase into the poem, as if wryly to challenge a possible doubt. In another case (find it for yourself) the challenging line is:

Brain in its bone-hood ticks in the drizzle

"The Sticks" mercilessly places the poet, the person, in a particular chance context that widens suddenly into the circumstance of everyman. These instances represent the book's preponderant qualities. The outcry at the heart is almost always contained within a reticent discipline. At least once, in "Witness to Death," the words rise in plain fury and despair. The conclusion:

I hate death. I hate all who speak well of it. Dunbar, Nashe, Villon, we sang as best we could for the sake of those who are gone, and it does no good.

Professor of Belles Lettres

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLife with Uncle

April 1967 -

Feature

FeatureDICK'S HOUSE

April 1967 -

Feature

FeatureUNCLE SAM AT DARTMOUTH

April 1967 By C. E. W. -

Article

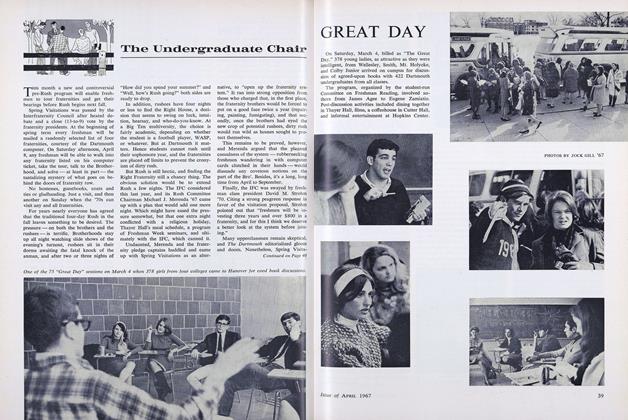

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleEloquence at Gettysburg and Daniel Webster

April 1967 By EARL W. WILEY '08 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1967 By MACOMBER, JOHN s. MAYER

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Books

BooksTHE FIVE HUNDRED HATS OF BARTHOLOMEW CUBBINS

January 1939 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksA MIRROR FOR AMERICANS. LIFE AND MANNERS IN THE UNITED STATES 1790-1870 AS RECORDED BY AMERICAN TRAVELERS.

January 1953 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksIN A SPERM WHALE'S JAWS

October 1954 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksEUGEN ROSENSTOCK-HUESSY: BIBLIOGRAPHY-BIOGRAPHY.

December 1959 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksCOLLECTED POEMS 1930-1960.

February 1961 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksROBERT SALMON: PAINTER OF SHIP & SHORE.

DECEMBER 1971 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

November, 1924 -

Books

BooksGUIDE TO MODERN ENGLISH.

July 1955 By HARRY T. SCHULTZ '37 -

Books

BooksTHE COURT OF VENUS.

May 1956 By L.D. PEARSON -

Books

BooksNot for Art's Sake

APRIL 1982 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMyth and Counter-Myth

NOVEMBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksThe Other Half

APRIL 1984 By Shelby Smith Grantham

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Books

BooksTHE FIVE HUNDRED HATS OF BARTHOLOMEW CUBBINS

January 1939 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksA MIRROR FOR AMERICANS. LIFE AND MANNERS IN THE UNITED STATES 1790-1870 AS RECORDED BY AMERICAN TRAVELERS.

January 1953 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksIN A SPERM WHALE'S JAWS

October 1954 By ALEXANDER LAING '25