THE second Tuesday in March is always a big day in Hanover. On that day all elements in the community, merchants, farmers, and educators, meet in the pure democratic assembly of a New England Town Meeting to air their common difficulties and decree a government for the ensuing year. Although the efficiency of a town meeting as an instrument of government may be doubted, it is the only known method whereby the people can govern themselves without resort to the principle of representation. The fact is that the town as a unit of government should continue to have enduring strength in Hanover and surrounding towns in view of the unique local history that lies behind it.

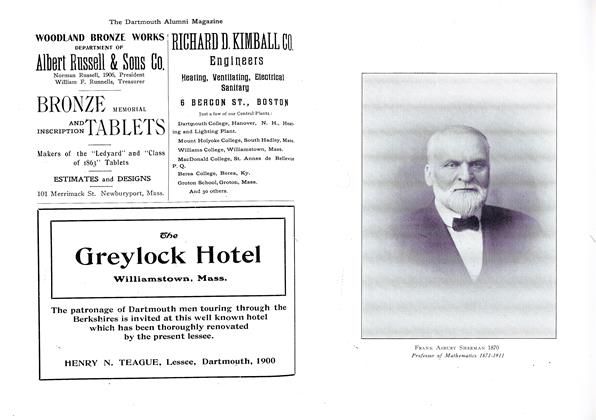

One of the most extraordinary political movements in New England in the eighteenth century was the attempt to make Hanover the capital of a republic. The movement was synchronous with the American Revolution, but was not aimed at the Crown of Great Britain. The fundamental grievance was against the provincial government of New Hampshire which tried to apply a system of representation which the people of Hanover would not brook. Substantially, it proposed to combine certain towns for the purposes of representation and assign, for instance, one representative to two thinly populated towns. What was the result? Under the leadership of Bezaleel Woodward, first librarian of Dartmouth College, and other Dartmouth savants the region rose in protest and there began to be issued from the press that had been set up in Hanover in 1778 a series of remarkable pamphlets and broadsides.

The tendency of late among historians has been to make the American Revolution too much a matter of trade and commodities. Hanover is one place where it is possible to isolate the germ of disaffection. What was here agitating the minds of the people appears to have been not a commercial consideration, but a political idea. At one time during the Revolution the people of the community offered to raise and finance a large expedition to invade Canada, but when any one suggested transcending the boundaries of towns for representative purposes local attention was at once directed to this political issue. Said the College Hall Address of 1776, one of the opening shots, "every body politic, incorporated with the same powers and privileges, whether large or small, is legally the same."

HANOVER A SOVEREIGN STATE

As the government of New Hampshire, during this period first at Portsmouth and then at Exeter, did not accept the divine right of the town idea, the College Party at once set about to establish the right of the Connecticut Valley towns to secede and form a new state under the leadership of Hanover. It is at this point that an abstract theory gripped the imagination of men like Bezaleel Woodward and furnished a plausible pretext for secession. That idea was the compact theory of government. A pamphlet now in the College Library Archives held that by the Declaration of Independence the people of New Hampshire were returned to a state of nature. In other words the people of New Hampshire were considered originally to have made a contract with the King whereby in return for the privilege of taxation and other considerations he gave them government and protection. When the royal bond was dissolved, the power to govern reverted to the people, who were the other party to the compact.

An interesting subject for investigation is the origin of the political theories which are set forth in the College Hall Address and the Public Defense. The latter, published in 1778, is best explained by its title, "Public Defense of the Right of the New Hampshire Grants, socalled on both sides of the Connecticut river, to associate together and form themselves into an independent State." Both these documents are pregnant with seventeenth century philosophy. The idea of a compact was obviously strong in the minds of the first Pilgrims as they entered one in 1620 before landing from the Mayflower. The principal political philosophers of that century like Hobbes and Locke built upon the compact theory as a foundation. The church covenant was a form of compact with which the people of the age had intimate acquaintance. But from what sources specifically did Bezaleel Woodward and his associates in the following century derive their ideas?

On the mezzanine floor of the library is housed the first library of Dartmouth College—the collection over which Bezaleel Woodward presided. The great majority of the books are of a religious nature; a few are his- Tories, travel books, and there are two significant books on political theory. The first of these is Locke's SecondTreatise on Government. In the light of the PublicDefense which has plenty to say about the state of nature it would have been strange if this book had not turned up. Some constitutional theorists have maintained that the Colonists had not accepted the transference of sovereignty from King to Parliament accomplished by the Revolution of 1688, but if this is so they certainly accepted the teachings of Locke who was the philosopher of that Revolution. The broadsides and pamphlets published at the period in Hanover reek with the ideas found in the Second Treatise.

The fact is, however, that this volume of Locke shows no particular signs of wear and tear. It may have been too long for immediate use and quotation by the political philosophers of Hanover. The substitute that was used is probably a pamphlet which is well fingered entitled, "The Judgment of Whole Kingdoms and Nations Concerning the Rights, Powers, and Prerogative of King and the Rights, Privileges, and Properties of the People." This pamphlet which has been attributed to Daniel Defoe has its salient passages underscored in ink, probably by Woodward. Its main thesis is the inability of the King or his subjects to depart from a compact once entered into. Anarchy and a state of nature, consequently, were the only logical results of the Declaration of Independence of 1776.

UNITED STATES OF CONNECTICUT

All this subversive doctrine that was struck off from the Hanover Press and directed at the government of New Hampshire did not, as we know, bear fruit in the way of a permanent organization of the Connecticut "Valley Towns into a Republic. Hanover and surrounding towns finally surrendered and rejoined New Hampshire when Congress so decreed, "V ermont turned a deaf ear to further entreaties for union, and the New Hampshire Assembly took peremptory charge of the situation in the early 1780's.

The Hanover uprising was, however, by no means altogether a failure. For a time the movement had every appearance of success. In retrospect the exaggerated importance that was then given to the town as an indestructible unit of government has persisted. The authors of the Public Defense brought with them from Connecticut a sacred conception of the town, fortified their conceptions with seventeenth century political philosophy, and bequeathed to their descendants a form of local government which is the last resource of government by the people. One of the institutions that owes something to men like Bezaleel Woodward is the New England Town Meeting. Probably the New Hampshire Legislature, the largest and most unwieldy in the Union because the towns still refuse to be denied full representation, is another illustration of the spell which seventeenth century philosophy still casts over the modern body politic. When it is a question of large political entities, state or national, the New England town idea must be considered a centrifugal force, but as long as it survives it will always be a strong redoubt of individual liberty.

SPIRIT OP INDEPENDENCE

As a philosophical tour de force the contract theory of government was clever and historically defensible. But the political gregariousness that was implicit in the thinking behind it has caused it to emerge from the borderland of theory and fancy where most people perhaps would place it and make itself felt in the economic and social life of the community. The most nonchalant examination of local history and life soon reveals in the people of Hanover a certain genius for self help and effective organization. The fact is that when any group of people in the community saw something that needed doing they at once set out to do it in accordance with their own convenience and resources. That something might seem to an outsider to carry with it the invasion of the rights of the general government, but when the general government had neither the will nor the way to accomplish the end desired, no one had the right to kick. Sometimes the result involved the ownership of considerable property for common ends, but capitalism has no occasion for alarm as it has been a commune without proselytizing zeal.

A fair example of the private initiative in practice is the Hanover Aqueduct Association, a corporation formed in 1821 to supply the share-holders with water from springs on the south side of Mink Brook. Many people in Hanover are members of this Association today and use its water as an auxiliary supply. Similarly and quite apart from any governmental direction different sections of the town organized companies to build sewerage systems. There have been for this purpose a North Company and a South Company, the original incorporators of which charge a fee to new comers and distribute the profits among themselves.

Another early expression of the social instinct in Hanover was the Hanover Ornamental Tree Association. In 1843 it appeared to certain people that Hanover needed m ore shade trees on its streets and accordingly they formed an organization to plant them. This organization, although ephemeral, was the first of several which have undertaken to improve the physical aspects of the town as well as its recreational facilities. A notable successor is the Pine Park Association which came into existence when fifteen or more prominent citizens raised among themselves enough money to buy the attractive stretch of woodland that follows the curve of the River beyond Occum Ridge and bounds the Golf Links to the west and north. The purpose of this organization as defined in 1905 was "to promote the public health, growth, and material prosperity of the village of Hanover." It is this happy coincidence between private initiative and common good which lends a certain amount of philosophical color and novelty to local life.

An urge to group activity has persisted to the present as a fruitful source of community endeavor. The profits of the local theater beyond a certain amount are distributed to the town in the form of new sidewalks or fire apparatus as a result of the incorporation in 1922 by a few citizens of the Hanover Village Improvement Society. A Business Men's Association formed in 1911 to establish cordial relations with each other and local farmers was the predecessor of the local chapter of the Rotary Club. In this organization and in others like the Parent-Teachers' Association there is a democratic quality which is in strict accord with Hanoverian tradition.

The title of this article—the Republic of Hanovermay be a misnomer for something that is more like a commune than a representative democracy. There is a haphazardness about the Hanover scheme which combines the urgency of the present with a long past and defies exact analysis. The historian may have to search out the origin of its unwritten constitution in 17th century England—perhaps even in the forests of Ancient Germany—in colonial Connecticut and Massachusetts and perhaps even more in the realms of pure idea and political expediency. Not that its mode of life has been essentially different from what one might call the New England way, but that that way has undergone local mutations along the lines of individual and group initiative. The anarchy that was thought by Hanover intelligentsia to have resulted when they threw over George 111 proved to have a constructive side. Although individual citizens were free in theory to pursue their own inclinations, their consistent choice has been the subordination of personal to general good.

Of course it might be well to subject some of this interpretation to the well-known process which is called "debunking." The men of Hanover in '76 may have had just enough honesty to require a rational explanation for their revolutionary conduct. Hence they took refuge in an idea, somewhat flattering to themselves and slightly fastidious in conception, which had been struck from the cynical brain of Thomas Hobbes and patented by John Locke. Again, it was often true that when neighbors joined in a mutual enterprise, it was because they could do hardly less. If the power which had been granted to the Precinct, let us say, was inadequate to cover the ordinary demands of local government such as police and fire protection, any organization of citizens to supply the want was not so much a manifestation of the principle of self-denial as that of self-preservation. Such an interpretation, however, does not alter the facts. Whatever the motivating force, it resulted in the pooling of individual resources and brought about a distinctive political pattern. The idea of a social compact probably sank into the "deep well" of subconscious thought, but there remains to give a recognizable continuity to local life.

WHERE HANOVER VOTED Old G. A. R. Building used as Precinct Hall for yearsfourth on left hand side of street

BEZALEEL WOODWARD

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

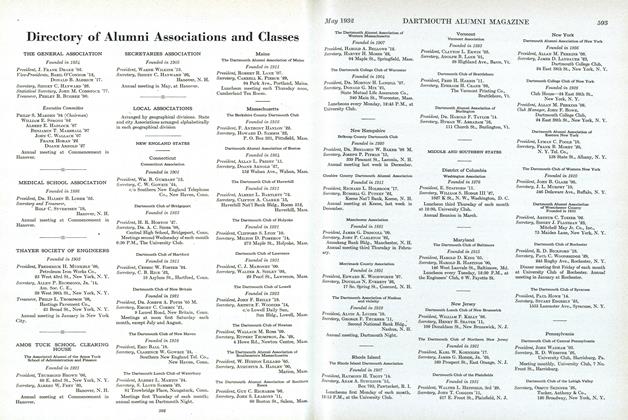

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

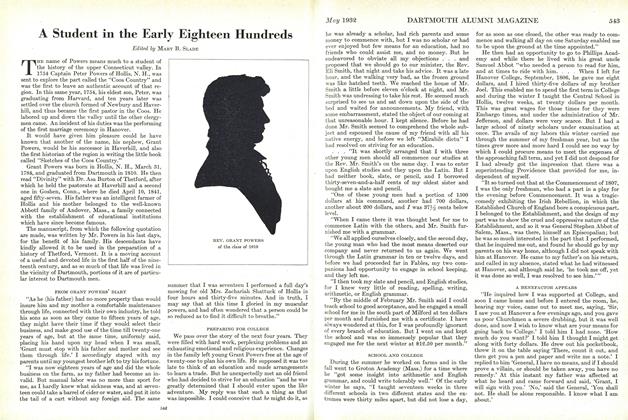

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

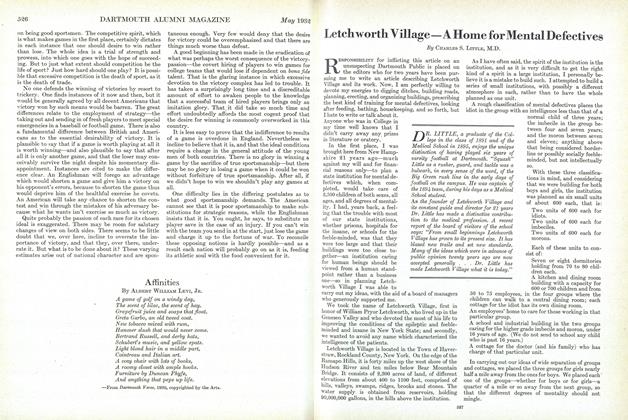

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D.