The Harvard Alumni Bulletin for April thirtieth contains this eminently sensible comment on a new kind of "commercialism" charge:

"Recent events at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and (it is reported) at the University of Chicago, have created a new burning issue in educational circles. Howfar shall a member of the teaching staff of a college or university engage in outside activities? And if he does such outside work shall he divide the profits with the institution to which he belongs? Dr. James Geddes, 'BO, Professor of Romance Languages at Boston University, has recently contributed a letter to the Boston Herald in which he examines the question at length and concludes that all things considered it is best to leave things as they are. Professor Geddes has made at least one thing Clear, namely, that there are a good many things to be considered before any step is taken to restrict the teacher's liberty to dispose of his free time as he deems best.

"On some points there will be no disagreement. A member of the Faculty of an institution of higher learning has two functions, teaching and research. In the exercise of both of these functions he should be devoted to the discovery and propagation of the truth as he sees it. His intellectual honesty should be above reproach, and there should be no suspicion that his opinions are purchasable. Fundamentally, he should be disinterested, and not commercially-minded. If outside activities were to corrupt this essential integrity of mind, it might be necessary to control them. It is also obvious that outside activities should not be allowed to trespass unduly upon a teacher's time. His instruction and research are a prior obligation. Finally, if in his outside activities, for which he is paid, a teacher makes use of materials, laboratory space, or other facilities of the institution, there can be no reasonable objection to his paying for them.

"None of these points, however, argue in support of a division of the profits. Such a policy would not have the effect of reducing the time given to outside activities, but might increase it. There would be no reduction of the commercial motive, but rather a tendency to strengthen it, and to involve the institution as well, perhaps to an extent that might easily strengthen existing doubts as to exemptions from taxation. And such a policy would necessarily be restrictive and intrusive. If it is to be adopted at all there is no reason in principle why it should not be extended to authors' royalties and lecture-fees, but to subject all of a teacher's gainful employment to supervision would imply a degree of interference that is contrary to the whole spirit of college and university teaching.

"It is believed that the right way to control the student's time is not by prohibitions but by high standards of attainment. If he does well what is asked of him, we say, let him dispose of the rest of his time as he sees fit. Why not apply the same method to teachers and scholars? Appoint and promote good teachers and sound scholars, and eave the rest to them. If outside activities are regarded as an evil, limit them by encouraging other activities. Reward what you want to secure instead of penalizing what you want to discourage. If, on the other hand, outside activities are regarded as a good thing, because they bring the teacher or scholar into contact with contemporary life, why not encourage them by permitting the teacher to reap the full benefits which accure from them?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

June 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleA Senior Fellow's Journey

June 1931 By John Butlin Martin, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

June 1931 By F. W. Andres -

Article

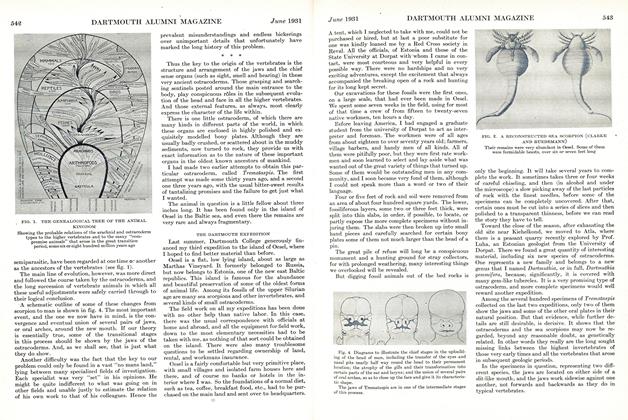

ArticleThe Dartmouth Expedition to the Island of Oesel

June 1931 By Wm. Patten -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931

Article

-

Article

ArticleTrustee Meeting

MAY 1932 -

Article

ArticleNew Council Approved

June 1938 -

Article

ArticleThe Author

March 1952 -

Article

ArticleTHE FBI AND ME or, How I Didn't Shoot Eisenhower

November 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING'25 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

December 1960 By GEORGE P. DROWNE JR. '33 -

Article

ArticleCider and Doughnuts

October 1976 By PIERRE KIRCH '78